- Mar 11, 2015

- 77,002

- 34,229

- 2,330

Of course you don't.What law did she break? Im not saying she isnt a bitch, but im not seeing a crime.

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature currently requires accessing the site using the built-in Safari browser.

Of course you don't.What law did she break? Im not saying she isnt a bitch, but im not seeing a crime.

So was the guy who killed Medgar Evers, but he was sent to prison after a second trial so it can happen.They were already tried and acquitted so there is nothing that could be done legally. It's called double jeopardy.

It's still racist now. You want to compare something but if it had it not been for Ahmaud Arberys parents, his murder would have been covered up by the police in Georgia.What happened to Emmett Till was horrific, but unfortunately there is no crime for which she could be prosecuted. While I of course learned of this case as a teen, and knew the white men were acquitted, I investigated it further after reading OP’s post to learn why the Grand Jury did not indict the woman whose false account led to the murder.

The federal government found that they did not have sufficient evidence that her lie instigated the murder, as she denied recanting the original story. As far as prosecuting her for perjury, rather than for instigating a murder, that would have been in state court, and the state limitation would have run out.

The fact that the all-white jury acquitted the murderers does show, tragically, how racist it was in the South back then. Compare that to the recent case where the father-and-son killed the black man running down the street, and a third man who was filming it was ALSO sentenced to life in prison.

So while we recognize how unjust the system was in 1950s Mississippi when a white killed a black - which everyone knows - I think it is important to recognize how much progress made in the generations since then. In fact, in some cases, it has swung to the opposite extreme, most famously with OJ Simpson. By and large, the lopsided treatment of white murderers of black victims has died with the Old South.

May Emmett Till RIP.

Federal Officials Close Cold Case Re-Investigation of Murder of Emmett Till

The Department of Justice’s Civil Rights Division and the U.S. Attorney’s Office for the Northern District of Mississippi announced today that it has closed its investigation into a witness’s alleged recantation of her account of the events leading up to the murder of Emmett Till. The...www.justice.gov

De la Beck had two hung juries before being convicted. Double jeopardy didn’t apply. It only applies to a completed trial with a verdict.So was the guy who killed Medgar Evers, but he was sent to prison after a second trial so it can happen.

And it was a THIRD trial, not a second one.So was the guy who killed Medgar Evers, but he was sent to prison after a second trial so it can happen.

There is no statute of limitations on murder.We have statutes of limitations for sound reasons. One of the biggest reasons is testimony and proof get LESS certain with time.

They always try looking for reasons to deny.There is no statute of limitations on murder.

There are individuals who will go to their graves still denying that there exists any difference in the way Black people in the United States are treated versus the way many White people are treated.

When it comes to crimes, modern day crimes, I have long been documenting the differences in the way a criminal report is [allowed to be] lodged, the allegations investigated, the case referred/recommended for prosecution, then the perpetrator(s) charged, tried and sentenced when the victim is Black and the perpetrator is White.

There is no status of limitations on murder therefore no justice to be had for the family of Emmett Till but our Justice department was able to do this on behalf of the Jewish people, who for the most part are White:

There is a division within the Department of Justice set up to root out in the U.S. participants at any level in the European Holocaust for prosecution. I am intimate with this work: I ran a division at the Justice Department that supported it and pushed for legislation for compensation for Holocaust victims. And that work inspired me to commit to bring similar focus and energy to analogous cases of civil rights murder, including volunteering to help members of the Till family and their supporters draw attention to the history.In one example of the prosecutions of Nazis, America extracted a 95-year-old from his home and medevaced him to Germany for lying on his immigration form when he entered the U.S. There was no bureaucratic concern about statutes of limitations on perjury; there was no plea for compassion because of the reach of time, frailty or the possible pressure that these young people endured by Nazi commanders. I’m proud of this work. The Justice Department’s long-term effort to root out those who supported Germany’s state genocide is among America’s strongest examples of its defense of human and civil rights. And the principle behind it is not retribution but an aspect of declaring “never again”: the forward-looking value that teaches people that ***this evil, even when carried out by the foot soldiers***, cannot be pardoned or explained away***.

Opinion | What hunting Nazis tells us about the case of Emmett Till

Emmett Till had a last chance at justice. And we wasted it.What does it say about us — not the woman who accused him — that she has escaped justice?

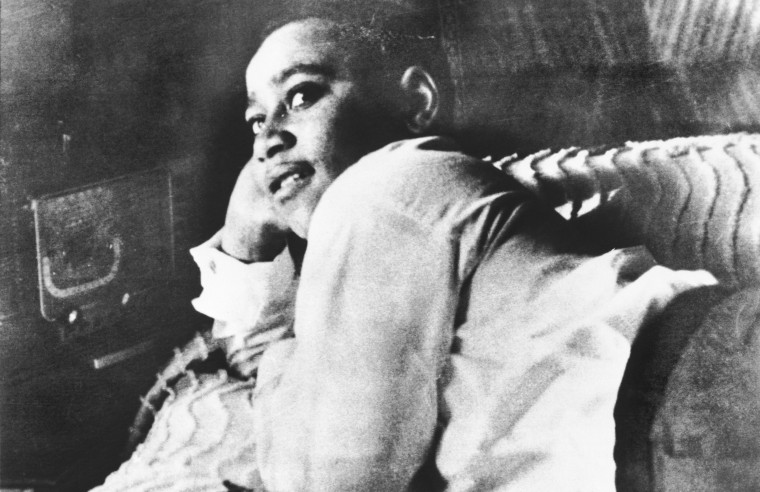

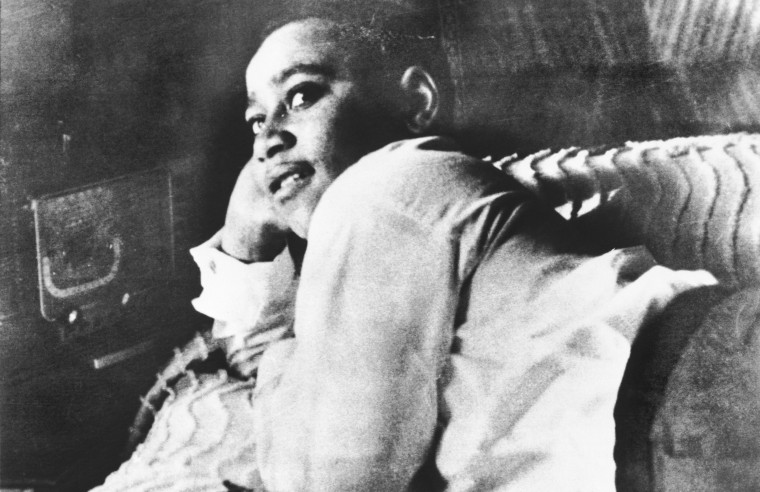

Emmett Till in 1954.Bettmann Archive via Getty Images

Aug. 10, 2022, 3:26 PM PDTBy Robert Raben, former assistant attorney generalEmmett Till, 14, was tortured to death on an August night in 1955 in a sweltering farm shed in Mississippi. His cries and moans went on for hours, heard by the nearby farmers. We know who bludgeoned him to death, since J.W. Milam and Roy Bryant admitted to committing the crime in the story they sold for $4,000 to Look magazine.But no one was ever punished.Today, hiding in plain sight is the last living person who could be held accountable: Carolyn Bryant Donham, the white woman whose story about Till’s confronting her while she was tending to her store alone at night triggered the monstrous extrajudicial response of her husband and other relatives, lives in North Carolina.It can seem like the time for incarcerating her has passed. But justice demands accountability in whatever time is left.The revelation this summer of a 1955 warrant for her arrest gave hope to Till’s family that justice might finally be served. But an aide to Mississippi Attorney General Lynn Fitch last month boldly said there was no new evidence to justify her arrest, and it was announced Tuesday that a grand jury had declined to indict her.In the years following Till’s death, Donham married twice, took classes at Delta State University and made jewelry that she sold at arts and crafts shows. She popped up on Facebook under an assumed name, tended to her dogs and lived a life devoid of one notable thing: punishment.But the debate about whether or not the facts compel her indictment is actually the sideshow; on the main stage is a much harder question: What does it say about us — not her — that she has escaped justice?At the time of Till’s death, the Leflore County, Mississippi, sheriff told reporters he did not want to “bother” Donham because she had two young children to care for. Today, she’s in her late 80s, and it can seem like the time for incarcerating her has passed.But justice demands accountability in whatever time is left. This principle has guided America’s policy in extraditing elderly Holocaust perpetrators back to Europe in the belief that they must pay for their crimes however possible — that if the only punishment left to be meted out is the denial of freedom in old age, than that’s the sentence that must be delivered.

Aug. 10, 202201:43

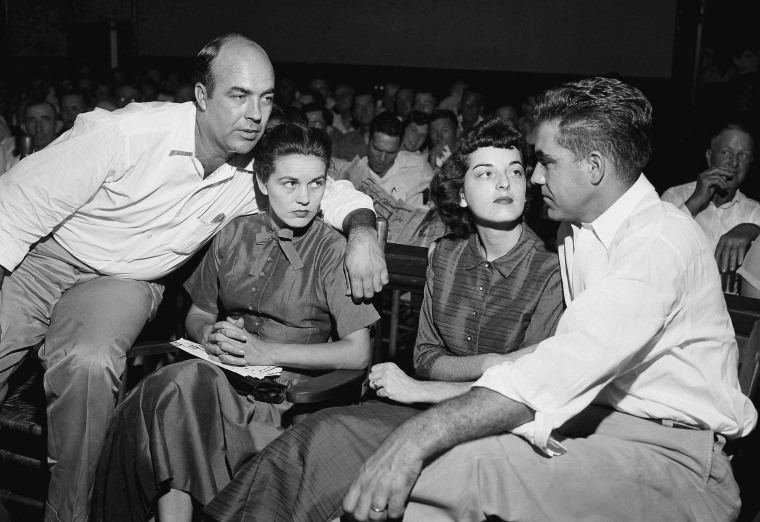

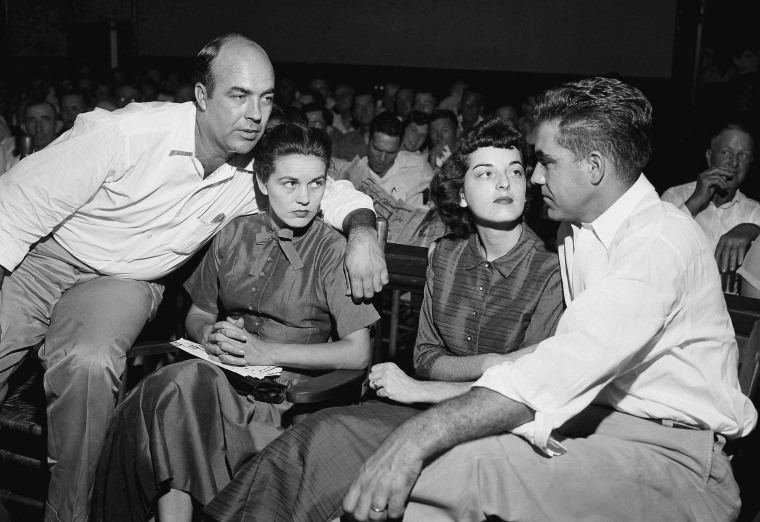

There is a division within the Department of Justice set up to root out in the U.S. participants at any level in the European Holocaust for prosecution. I am intimate with this work: I ran a division at the Justice Department that supported it and pushed for legislation for compensation for Holocaust victims. And that work inspired me to commit to bring similar focus and energy to analogous cases of civil rights murder, including volunteering to help members of the Till family and their supporters draw attention to the history.In one example of the prosecutions of Nazis, America extracted a 95-year-old from his home and medevaced him to Germany for lying on his immigration form when he entered the U.S. There was no bureaucratic concern about statutes of limitations on perjury; there was no plea for compassion because of the reach of time, frailty or the possible pressure that these young people endured by Nazi commanders.I’m proud of this work. The Justice Department’s long-term effort to root out those who supported Germany’s state genocide is among America’s strongest examples of its defense of human and civil rights. And the principle behind it is not retribution but an aspect of declaring “never again”: the forward-looking value that teaches people that this evil, even when carried out by the foot soldiers, cannot be pardoned or explained away.J.W. Milam, left; his wife, second left; Roy Bryant, far right; and his wife, Carolyn Bryant, in a courtroom in Sumner, Miss., on Sept. 23, 1955.AP We are not applying this same effort to punishing the white women who played a crucial role in sending Black men to their deaths, however. Donham set in motion the events that led to Till’s ghastly demise. Donham told the court that “this n----- man” had grabbed her hand at the cash register and said, “How about a date, baby?” She testified that she turned around and that Till then, from behind, put his left hand on her waist and his right arm on her hip and said, “What’s the matter baby, can’t you take it?” and uttered a vulgarity.

We are not applying this same effort to punishing the white women who played a crucial role in sending Black men to their deaths, however. Donham set in motion the events that led to Till’s ghastly demise. Donham told the court that “this n----- man” had grabbed her hand at the cash register and said, “How about a date, baby?” She testified that she turned around and that Till then, from behind, put his left hand on her waist and his right arm on her hip and said, “What’s the matter baby, can’t you take it?” and uttered a vulgarity.

But she later said that never happened. Till’s cousins, also teens and present at the time, said that at most he whistled at her, and even that is disputed by others at the scene. Her husband and brother-in-law were acquitted by the jury of their peers after just over an hour of deliberation. Donham did not even have to face that trifling consequence.Yet she is as responsible as her husband and kin who bludgeoned the boy to death. Our prisons are filled with Black men (and women) who participated in far less depraved crimes, but we do not have a culture that protects them. To find Donham guilty, though, would mean admitting a terrible flaw in our own culture.After public pressure, in 2006 a local prosecutor in Leflore County, Mississippi, had a grand jury consider bringing manslaughter charges against her at the conclusion of an FBI investigation that had led nowhere. The grand jury found insufficient evidence, however, so there were no charges.After the author Tim Tyson revealed in his 2017 book “The Blood of Emmett Till” that Donham had recanted her testimony, Attorney General Jeff Sessions had the Justice Department reopen the matter to see whether there was any way the federal government could intervene. That, too, fizzled. And this week, again, it was the same story.To be clear, this is not a failure of will of the prosecutors. ***This is a cultural failure***.In 2018 Sessions praised the work of the Justice Department’s best-known Nazi hunter, Eli Rosenbaum, and his team for successfully removing the 68th Nazi from the U.S. The passage of time did not deter the department from fulfilling its moral imperative of seeking justice for the victims of the Holocaust.Yet in 2022, in the case of Emmett Till, we hear the silence and our own nation’s complicity. In Western Europe, the mechanisms of the state, civil society and culture are conducting an inquiry into the past and its key perpetrators. In the U.S., we are not owning up to these chronic monstrosities nor holding enough among us accountable.

You cite them since you have the problem.Cite them.

When they have the will (to obtain justice for certain people) they FIND a way:The comparison UNFORTUNATELY -- is a little lopsided. First off -- the Nazi Berger was living in Tenn at the time he was EXTRADICTED to GERMANY for the trial. There's no limit to Germans trying to ASSUAGE THEIR GUILT by hunting and prosecuting Nazis. He was the 70th Nazi big guy found in the US and sent to the Germans. SO -- that wasn't a "one -- of" ...

I was VERY uncomfortable working in Germany when folks would randomly apologize to me for the Holocaust. Otherwise -- they are fine people. Just got a "Nazi guilt derangement syndrome" or NGDS for short. AND IT'S HEREDITARY. For 3 or more generations now in the German population.

As sad as that original rigged trial was --- and the murderers being set free only to COP to the murder for money from a magazine -- The wife -- was guilty of perjury. And MAYBE had the warrant been served in a timely fashion "accessory" to murder.

SO -- digging up a Nazi sent back to Germany on REQUEST of Germany who oversaw MASSIVE human suffering and death is not really an AMERICAN story to compare to totally screwed up justice in 50s America. DEFINITELY sick racist stuff. But -- Other known murderers have walked only to come clean decades later.

Getting "justice" for that horrific act was just not possible 50 years later when THREE DOJustice investigations found NO AVENUES for prosecution of the wife. We have statutes of limitations for sound reasons. One of the biggest reasons is testimony and proof get LESS certain with time.

Well, boys, you've done a good job. You've struck a blow for the white man. Mississippi can be proud of you. You've let those agitating outsiders know where this state stands. Go home now and forget it. But before you go, I'm looking each one of you in the eye and telling you this: The first man who talks is dead! If anybody who knows anything about this ever opens his mouth to any outsider about it, then the rest of us are going to kill him just as dead as we killed those three sonofbitches [sic] tonight. Does everybody understand what I'm saying? The man who talks is dead, dead, dead![27]

Unconvinced by the assurances of the Memphis-based agents, Sullivan elected to wait in Memphis ... for the start of the "invasion" of northern students ... Sullivan's instinctive decision to stick around Memphis proved correct. Early Monday morning, June 22, he was informed of the disappearance ... he was ordered to Meridian. The town would be his home for the next nine months.— Cagin & Dray, We Are Not Afraid, 1988[28]

I blame the people in Washington DC and on down in the state of Mississippi just as much as I blame those who pulled the trigger. ... I'm tired of that! Another thing that makes me even tireder though, that is the fact that we as people here in the state and the country are allowing it to continue to happen. ... Your work is just beginning. If you go back home and sit down and take what these white men in Mississippi are doing to us. ... if you take it and don't do something about it. ... then God damn your souls![32][43]

"To many it will always be June 21, 1964, in Philadelphia."— Cagin & Dray, We Are Not Afraid, 1988[50]

How about conspiracy to commit murder?Cite them.

She was a member of a conspiracy to murder Till.What law did she break? Im not saying she isnt a bitch, but im not seeing a crime.

TEACH!When they have the will (to obtain justice for certain people) they FIND a way:

The Enforcement Act of 1871 (17 Stat. 13), also known as the Ku Klux Klan Act, Third Enforcement Act,[1] Third Ku Klux Klan Act,[2] Civil Rights Act of 1871, or Force Act of 1871,[3] is an Act of the United States Congress which empowered the President to suspend the writ of habeas corpus to combat the Ku Klux Klan (KKK) and other terrorist organizations. The act was passed by the 42nd United States Congress and signed into law by United States President Ulysses S. Grant on April 20, 1871. The act was the last of three Enforcement Acts passed by the United States Congress from 1870 to 1871 during the Reconstruction Era to combat attacks upon the suffrage rights of African Americans. The statute has been subject to only minor changes since then, but has been the subject of voluminous interpretation by courts.[snipped]Although some provisions were ruled unconstitutional in 1883,[41] the 1870 Force Act and the 1871 Civil Rights Act have been invoked in later civil rights conflicts, including the 1964 murders of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner;The murders of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner, also known as the Freedom Summer murders, the Mississippi civil rights workers' murders, or the Mississippi Burning murders, refers to events in which three activists were abducted and murdered in the city of Philadelphia, Mississippi, in June 1964 during the Civil Rights Movement. The victims were James Chaney from Meridian, Mississippi, and Andrew Goodman and Michael Schwerner from New York City. All three were associated with the Council of Federated Organizations (COFO) and its member organization, the Congress of Racial Equality (CORE). They had been working with the Freedom Summer campaign by attempting to register African Americans in Mississippi to vote. Since 1890 and through the turn of the century, southern states had systematically disenfranchised most black voters by discrimination in voter registration and voting.The three men had traveled from Meridian to the community of Longdale to talk with congregation members at a black church that had been burned; the church had been a center of community organization. The trio was arrested following a traffic stop for speeding outside Philadelphia, Mississippi, escorted to the local jail, and held for a number of hours.[1] As the three left town in their car, they were followed by law enforcement and others. Before leaving Neshoba County, their car was pulled over. The three were abducted, driven to another location, and shot to death at close range. The bodies of the three men were taken to an earthen dam where they were buried.[1]There is a federal statute 'conspiracy to commit murder'

18 U.S. Code § 1117 - Conspiracy to murderIf two or more persons conspire to violate section 1111(Murder) , 1114, 1116, or 1119 of this title, and one or more of such persons do any overt act to effect the object of the conspiracy, each shall be punished by imprisonment for any term of years or for life.

The conspiracy

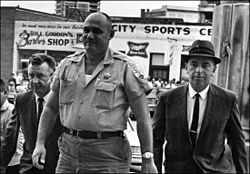

Parties to the conspiracy; Top row: Lawrence A. Rainey, Bernard L. Akin, Other "Otha" N. Burkes, Olen L. Burrage, Edgar Ray Killen. Bottom row: Frank J. Herndon, James T. Harris, Oliver R. Warner, Herman Tucker and Samuel H. Bowers[citation needed]Nine men, including Neshoba County Sheriff Lawrence A. Rainey, were later identified as parties to the conspiracy to murder Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner.[12] Rainey denied he was ever a part of the conspiracy, but he was accused of ignoring the racially-motivated offenses committed in Neshoba County. At the time of the murders, the 41-year-old Rainey insisted he was visiting his sick wife in a Meridian hospital and was later with family watching Bonanza.[13] As events unfolded, Rainey became emboldened with his newly found popularity in the Philadelphia community. Known for his tobacco chewing habit, Rainey was photographed and quoted in Life magazine: "Hey, let's have some Red Man", as other members of the conspiracy laughed while waiting for an arraignment to start.[14]Fifty-year-old Bernard Akin had a mobile home business which he operated out of Meridian; he was a member of the White Knights.[12] Seventy one-year-old Other N. Burkes, who usually went by the nickname of Otha, was a 25-year veteran of the Philadelphia Police. At the time of the December 1964 arraignment, Burkes was awaiting an indictment for a different civil rights case. Olen L. Burrage, who was 34 at the time, owned a trucking company. Burrage was developing a cattle farm which he called the Old Jolly Farm, where the three civil rights workers were found buried. Burrage, a former U.S. Marine who was honorably discharged, was quoted as saying: "I got a dam big enough to hold a hundred of them."[15] Several weeks after the murders, Burrage told the FBI: "I want people to know I'm sorry it happened."[16] Edgar Ray Killen, a 39-year-old Baptist preacher and sawmill owner, was convicted decades later of orchestrating the murders.Frank J. Herndon, 46, operated a Meridian drive-in called the Longhorn;[12] he was the Exalted Grand Cyclops of the Meridian White Knights. James T. Harris, also known as Pete, was a White Knights investigator. The 30-year-old Harris was keeping tabs on the three civil rights workers' every move. Oliver R. Warner, 54, known as Pops, was a Meridian grocery owner and member of the White Knights. Herman Tucker lived in Hope, Mississippi, a few miles from the Neshoba County Fair grounds. Tucker, 36, was not a member of the White Knights; he was a building contractor who worked for Burrage. The White Knights gave Tucker the assignment of getting rid of the CORE station wagon driven by the workers. White Knights Imperial Wizard Samuel H. Bowers, who served with the U.S. Navy during World War II, was not apprehended on December 4, 1964, but he was implicated the following year. Bowers, then 39, was credited with saying: "This is a war between the Klan and the FBI. And in a war, there have to be some who suffer."[17]On Sunday, June 7, 1964, nearly 300 White Knights met near Raleigh, Mississippi.[18] Bowers addressed the White Knights about what he described as a "******-communist invasion of Mississippi" that he expected to take place in a few weeks, in what CORE had announced as Freedom Summer.[18] The men listened as Bowers said: "This summer the enemy will launch his final push for victory in Mississippi", and, "there must be a secondary group of our members, standing back from the main area of conflict, armed and ready to move. It must be an extremely swift, extremely violent, hit-and-run group."[18]Although federal authorities believed many others took part in the Neshoba County lynching, only ten men were charged with the physical murders of Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner.[19] One of these was Deputy Sheriff Price, 26, who played a crucial role in implementing the conspiracy. Before his friend Rainey was elected sheriff in 1963, Price worked as a salesman, fireman, and bouncer.[19] Price, who had no prior experience in local law enforcement, was the only person who witnessed the entire event. He arrested the three men, released them the night of the murders, and chased them down state Highway 19 toward Meridian, eventually re-capturing them at the intersection near House, Mississippi. Price and the other nine men escorted them north along Highway 19 to Rock Cut Road, where they forced a stop and murdered the three civil rights workers.Killen went to Meridian earlier that Sunday to organize and recruit men for the job to be carried out in Neshoba County.[20] Before the men left for Philadelphia, Travis M. Barnette, 36, went to his Meridian home to take care of a sick family member. Barnette owned a Meridian garage and was a member of the White Knights. Alton W. Roberts, 26, was a dishonorably discharged U.S. Marine who worked as a salesman in Meridian. Roberts, standing 6 ft 3 in (1.91 m) and weighing 270 lb (120 kg), was physically formidable and renowned for his short temper. According to witnesses, Roberts shot both Goodman and Schwerner at point blank range, then shot Chaney in the head after another accomplice, James Jordan, shot him in the abdomen. Roberts asked, "Are you that ****** lover?" to Schwerner, and shot him after the latter responded, "Sir, I know just how you feel."[21] Jimmy K. Arledge, 27, and Jimmy Snowden, 31, were both Meridian commercial drivers. Arledge, a high school drop-out, and Snowden, a U.S. Army veteran, were present during the murders.Jerry M. Sharpe, Billy W. Posey, and Jimmy L. Townsend were all from Philadelphia. Sharpe, 21, ran a pulp wood supply house. Posey, 28, a Williamsville automobile mechanic, owned a 1958 red and white Chevrolet; the car was considered fast and was chosen over Sharpe's. The youngest was Townsend, 17; he left high school in 1964 to work at Posey's Phillips 66 garage. Horace D. Barnette, 25, was Travis' younger half-brother; he had a 1957 two-toned blue Ford Fairlane sedan.[19] Horace's car is the one the group took after Posey's car broke down. Officials say that James Jordan, 38, killed Chaney. He confessed his crimes to the federal authorities in exchange for a plea deal.

MurdersAfter Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner's release from the Neshoba County jail shortly after 10 p.m. on June 21,[22] they were followed almost immediately by Deputy Sheriff Price in his 1957 white Chevrolet sedan patrol car.[23] Soon afterward, the civil rights workers left the city limits located along Hospital Road and headed south on Highway 19. The workers arrived at Pilgrim's store, where they might have been inclined to stop and use the telephone, but the presence of a Mississippi Highway Patrol car, manned by Officers Wiggs and Poe, most likely dissuaded them. They continued south toward Meridian.

Ford Station Wagon location near the Bogue Chitto River near Highway 21 (32°52′54.15″N 88°56′16.87″W)The lynch mob members, who were in Barnette's and Posey's cars, were drinking while arguing who would kill the three young men. Eventually, Burkes drove up to Barnette's car and told the group: "They're going on 19 toward Meridian. Follow them!" After a quick rendezvous with Philadelphia Police officer Richard Willis, Price began pursuing the three civil rights workers.Posey's Chevrolet carried Roberts, Sharpe, and Townsend. The Chevy apparently had carburetor problems, and was forced to the side of the highway. Sharpe and Townsend were ordered to stay with Posey's car and service it. Roberts transferred to Barnette's car, joining Arledge, Jordan, Posey, and Snowden.[24]Price eventually caught the CORE station wagon heading west toward Union, on Road 492. Soon he stopped them and escorted the three civil right workers north on Highway 19, back in the direction of Philadelphia. The caravan turned west on County Road 515 (also known as Rock Cut Road), and stopped at the secluded intersection of County Road 515 and County Road 284 (32°39′40.45″N 89°2′4.13″W). The three men were subsequently shot to death by Jordan and Roberts. Chaney was also beaten and castrated before his death.

Disposing of the evidence

The station wagon on an abandoned logging road along Highway 21After the victims had been shot and killed, they were quickly loaded into their station wagon and transported to Burrage's Old Jolly Farm, located along Highway 21, a few miles southwest of Philadelphia where an earthen dam for a farm pond was under construction.[25] Tucker was already at the dam waiting for the lynch mob's arrival. Earlier in the day, Burrage, Posey, and Tucker had met at either Posey's gas station or Burrage's garage to discuss these burial details, and Tucker most likely was the one who covered up the bodies using a bulldozer that he owned. An autopsy of Goodman, showing fragments of red clay in his lungs and grasped in his fists, suggests he was probably buried alive alongside the already dead Chaney and Schwerner.[26]After all three were buried, Price told the group:

Eventually, Tucker was tasked with disposing of the CORE station wagon in Alabama. For reasons unknown, the station wagon was left near a river in northeast Neshoba County along Highway 21. It was soon set ablaze and abandoned.[citation needed]

President Lyndon B. Johnson signs the 1964 Civil Rights Act as Martin Luther King, Jr. and others look on, July 2, 1964.

Protest outside the 1964 Democratic National Convention; some hold signs with portraits of slain civil rights workers, August 24, 1964

Sheriff Lawrence A. Rainey being escorted by two FBI agents to the federal courthouse in Meridian, Mississippi; October 1964

After reluctance from FBI Director J. Edgar Hoover to get directly involved, President Lyndon Johnson convinced him by threatening to send ex-CIA director Allen Dulles in his stead.[29] Hoover initially ordered the FBI Office in Meridian, run by John Proctor, to begin a preliminary search after the three men were reported missing. That evening, U.S. Attorney General Robert F. Kennedy escalated the search and ordered 150 federal agents to be sent from New Orleans.[30] Two local Native Americans found the smoldering car that evening; by the next morning, that information had been communicated to Proctor. Joseph Sullivan of the FBI immediately went to the scene.[31] By the next day, the federal government had arranged for hundreds of sailors from the nearby Naval Air Station Meridian to search the swamps of Bogue Chitto.During the investigation, searchers including Navy divers and FBI agents discovered the bodies of Henry Hezekiah Dee and Charles Eddie Moore in the area (the first was found by a fisherman). They were college students who had disappeared in May 1964. Federal searchers also discovered 14-year-old Herbert Oarsby, and the bodies of five other deceased African Americans who were never identified.[32]The disappearance of Chaney, Goodman and Schwerner captured national attention. By the end of the first week, all major news networks were covering their disappearances. President Lyndon Johnson met with the parents of Goodman and Schwerner in the Oval Office. Walter Cronkite's broadcast of the CBS Evening News on June 25, 1964, called the disappearances "the focus of the whole country's concern".[33] The FBI eventually offered a $25,000 reward (equivalent to $218,000 in 2021), which led to the breakthrough in the case. Meanwhile, Mississippi officials resented the outside attention. Sheriff Rainey said, "They're just hiding and trying to cause a lot of bad publicity for this part of the state." Mississippi Governor Paul B. Johnson Jr. dismissed concerns, saying the young men "could be in Cuba".[34]The bodies of the CORE activists were found only after an informant (discussed in FBI reports only as "Mr. X") passed along a tip to federal authorities.[35] They were discovered on August 4, 1964, 44 days after their murder, underneath an earthen dam on Burrage's farm. Schwerner and Goodman had each been shot once in the heart; Chaney, a black man, had been severely beaten, castrated and shot three times. The identity of "Mr. X" was revealed publicly forty years after the original events, and revealed to be Maynard King, a Mississippi Highway Patrol officer close to the head of the FBI investigation. King died in 1966.[36][37]In the summer of 1964, according to Linda Schiro and other sources, FBI field agents in Mississippi recruited the mafia captain Gregory Scarpa to help them find the missing civil rights workers.[38] The FBI was convinced the three men had been murdered, but could not find their bodies. The agents thought that Scarpa, using illegal interrogation techniques not available to agents, might succeed at gaining this information from suspects. Once Scarpa arrived in Mississippi, local agents allegedly provided him with a gun and money to pay for information. Scarpa and an agent allegedly pistol-whipped and kidnapped Lawrence Byrd, a TV salesman and secret Klansman, from his store in Laurel and took him to Camp Shelby, a local Army base. At Shelby, Scarpa severely beat Byrd and stuck a gun barrel down his throat. Byrd finally revealed to Scarpa the location of the three men's bodies.[39][40] The FBI has never officially confirmed the Scarpa story. Though not necessarily contradicting the claim of Scarpa's involvement in the matter, investigative journalist Jerry Mitchell and Illinois high school teacher Barry Bradford claimed that Mississippi highway patrolman Maynard King provided the grave locations to FBI agent Joseph Sullivan after obtaining the information from an anonymous third party. In January 1966, Scarpa allegedly helped the FBI a second time in Mississippi on the murder case of Vernon Dahmer, killed in a fire set by the Klan. After this second trip, Scarpa and the FBI had a sharp disagreement about his reward for these services. The FBI then dropped Scarpa as a confidential informant.[41]

President Johnson and civil rights activists used the outrage over the activists' deaths to gain passage of the Civil Rights Act of 1964, which Johnson signed on July 2. This and the Selma to Montgomery marches of 1965 contributed to passage of the Voting Rights Act of 1965, which Johnson signed on August 6 of that year.Malcolm X used the delayed resolution of the case in his argument that the federal government was not protecting black lives, and African-Americans would have to defend themselves: "And the FBI head, Hoover, admits that they know who did it, they've known ever since it happened, and they've done nothing about it. Civil rights bill down the drain."[44][45]By late November 1964 the FBI accused 21 Mississippi men of engineering a conspiracy to injure, oppress, threaten, and intimidate Chaney, Goodman, and Schwerner. Most of the suspects were apprehended by the FBI on December 4, 1964.[46] The FBI detained the following individuals: B. Akin, E. Akin, Arledge, T. Barnette, Burkes, Burrage, Bowers, Harris, Herndon, Killen, Posey, Price, Rainey, Roberts, Sharpe, Snowden, Townsend, Tucker, and Warner. Two individuals who were not interviewed and photographed, H. Barnette and James Jordan, would later confess their roles during the murder.[47]Because Mississippi officials refused to prosecute the killers for murder, a state crime, the federal government, led by prosecutor John Doar, charged 18 individuals under 18 U.S.C. §242 and §371 with conspiring to deprive the three activists of their civil rights (by murder). They indicted Sheriff Rainey, Deputy Sheriff Price and 16 other men. A U. S. Commissioner dismissed the charges six days later, declaring that the confession on which the arrests were based was hearsay. One month later, government attorneys secured indictments against the conspirators from a federal grand jury in Jackson. On February 24, 1965, however, Federal Judge William Harold Cox, an ardent segregationist, threw out the indictments against all conspirators other than Rainey and Price on the ground that the other seventeen were not acting "under color of state law." In March 1966, the United States Supreme Court overruled Cox and reinstated the indictments. Defense attorneys then made the argument that the original indictments were flawed because the pool of jurors from which the grand jury was drawn contained insufficient numbers of minorities. Rather than attempt to refute the charge, the government summoned a new grand jury and, on February 28, 1967, won reindictments.[48]

1967 Federal trialMain article: United States v. PriceTrial in the case of United States v. Cecil Price, et al., began on October 7, 1967, in the Meridian courtroom of Judge William Harold Cox, the same judge known to be an opponent of the civil rights movement.[citation needed] A jury of seven white men and five white women was selected. Defense attorneys exercised peremptory challenges against all seventeen potential black jurors. A white man, who admitted under questioning by Robert Hauberg, the U.S. Attorney for Mississippi, that he had been a member of the KKK "a couple of years ago," was challenged for cause, but Cox denied the challenge.The trial was marked by frequent crises. Star prosecution witness James Jordan cracked under the pressure of anonymous death threats made against him and had to be hospitalized at one point. The jury deadlocked on its decision and Judge Cox employed the "Allen charge" to bring them to resolution. Seven defendants, mostly from Lauderdale County, were convicted. The convictions in the case represented the first ever convictions in Mississippi for the killing of a civil rights worker.[48]Those found guilty on October 20, 1967, were Cecil Price, Klan Imperial Wizard Samuel Bowers, Alton Wayne Roberts, Jimmy Snowden, Billy Wayne Posey, Horace Barnette, and Jimmy Arledge. Sentences ranged from three to ten years. After exhausting their appeals, the seven began serving their sentences in March 1970. None served more than six years. Sheriff Rainey was among those acquitted. Two of the defendants, E.G. Barnett, a candidate for sheriff, and Edgar Ray Killen, a local minister, had been strongly implicated in the murders by witnesses, but the jury came to a deadlock on their charges and the Federal prosecutor decided not to retry them.[30] On May 7, 2000, the jury revealed that in the case of Killen, they deadlocked after a lone juror stated she "could never convict a preacher".[49]

Further research and 2005 murder trial

State history marker for the bombing of the Mount Zion Methodist Church

For much of the next four decades, no legal action was taken regarding the murders. In 1989, on the 25th anniversary of the murders, the U.S. Congress passed a non-binding resolution honoring the three men; Senator Trent Lott and the rest of the Mississippi delegation refused to vote for it.[51]The journalist Jerry Mitchell, an award-winning investigative reporter for Jackson's The Clarion-Ledger, wrote extensively about the case for six years. In the late 20th century, Mitchell had earned fame by his investigations that helped secure convictions in several other high-profile Civil Rights Era murder cases, including the murders of Medgar Evers and Vernon Dahmer, and the 16th Street Baptist Church bombing in Birmingham.In the case of the civil rights workers, Mitchell was aided in developing new evidence, finding new witnesses, and pressuring the state to take action by Barry Bradford,[52] a high school teacher at Stevenson High School in Lincolnshire, Illinois, and three of his students, Allison Nichols, Sarah Siegel, and Brittany Saltiel. Bradford later achieved recognition for helping Mitchell clear the name of the civil rights martyr Clyde Kennard.[53]Together the student-teacher team produced a documentary for the National History Day contest. It presented important new evidence and compelling reasons to reopen the case. Bradford also obtained an interview with Edgar Ray Killen, which helped convince the state to investigate. Partially by using evidence developed by Bradford, Mitchell was able to determine the identity of "Mr. X", the mystery informer who had helped the FBI discover the bodies and end the conspiracy of the Klan in 1964.[54]Mitchell's investigation and the high school students' work in creating Congressional pressure, national media attention and Bradford's taped conversation with Killen prompted action.[55] In 2004, on the 40th anniversary of the murders, a multi-ethnic group of citizens in Philadelphia, Mississippi, issued a call for justice. More than 1,500 people, including civil rights leaders and Mississippi Governor Haley Barbour, joined them to support having the case re-opened.[56][57]On January 6, 2005, a Neshoba County grand jury indicted Edgar Ray Killen on three counts of murder. When the Mississippi Attorney General prosecuted the case, it was the first time the state had taken action against the perpetrators of the murders. Rita Bender, Michael Schwerner's widow, testified in the trial.[58] On June 21, 2005, a jury convicted Killen on three counts of manslaughter; he was described as the man who planned and directed the killing of the civil rights workers.[59] Killen, then 80 years old, was sentenced to three consecutive terms of 20 years in prison. His appeal, in which he claimed that no jury of his peers would have convicted him in 1964 based on the evidence presented, was rejected by the Supreme Court of Mississippi in 2007.[60]On June 20, 2016, Mississippi Attorney General Jim Hood and Vanita Gupta, top prosecutor for the Civil Rights Division of the U.S. Justice Department, announced that there would be no further investigation into the murders. "The evidence has been degraded by memory over time, and so there are no individuals that are living now that we can make a case on at this point," Hood said.[61]

Nobody should kill innocent people. You said blacks attacking Asians, there aren’t that many, yet complain when few cops kill blacks.Cops should not be killing ANY innocent people and more whites have attacked Asians. So dop your schitck because police have been murdering blacks for over 100 years and have gotten away with it.

So whats the crime?Of course you don't.

Except she didn’t murder anyone, and the crime is perjury - for which there is inadequate evidence.There is no statute of limitations on murder.

O. J. Simpson got away with the murder of two light skinned people. There was a stronger case against him.There are individuals who will go to their graves still denying that there exists any difference in the way Black people in the United States are treated versus the way many White people are treated.

When it comes to crimes, modern day crimes, I have long been documenting the differences in the way a criminal report is [allowed to be] lodged, the allegations investigated, the case referred/recommended for prosecution, then the perpetrator(s) charged, tried and sentenced when the victim is Black and the perpetrator is White.

There is no status of limitations on murder therefore no justice to be had for the family of Emmett Till but our Justice department was able to do this on behalf of the Jewish people, who for the most part are White:

There is a division within the Department of Justice set up to root out in the U.S. participants at any level in the European Holocaust for prosecution. I am intimate with this work: I ran a division at the Justice Department that supported it and pushed for legislation for compensation for Holocaust victims. And that work inspired me to commit to bring similar focus and energy to analogous cases of civil rights murder, including volunteering to help members of the Till family and their supporters draw attention to the history.In one example of the prosecutions of Nazis, America extracted a 95-year-old from his home and medevaced him to Germany for lying on his immigration form when he entered the U.S. There was no bureaucratic concern about statutes of limitations on perjury; there was no plea for compassion because of the reach of time, frailty or the possible pressure that these young people endured by Nazi commanders. I’m proud of this work. The Justice Department’s long-term effort to root out those who supported Germany’s state genocide is among America’s strongest examples of its defense of human and civil rights. And the principle behind it is not retribution but an aspect of declaring “never again”: the forward-looking value that teaches people that ***this evil, even when carried out by the foot soldiers***, cannot be pardoned or explained away***.

Opinion | What hunting Nazis tells us about the case of Emmett Till

Emmett Till had a last chance at justice. And we wasted it.What does it say about us — not the woman who accused him — that she has escaped justice?Emmett Till in 1954.Bettmann Archive via Getty Images

Aug. 10, 2022, 3:26 PM PDTBy Robert Raben, former assistant attorney generalEmmett Till, 14, was tortured to death on an August night in 1955 in a sweltering farm shed in Mississippi. His cries and moans went on for hours, heard by the nearby farmers. We know who bludgeoned him to death, since J.W. Milam and Roy Bryant admitted to committing the crime in the story they sold for $4,000 to Look magazine.But no one was ever punished.Today, hiding in plain sight is the last living person who could be held accountable: Carolyn Bryant Donham, the white woman whose story about Till’s confronting her while she was tending to her store alone at night triggered the monstrous extrajudicial response of her husband and other relatives, lives in North Carolina.It can seem like the time for incarcerating her has passed. But justice demands accountability in whatever time is left.The revelation this summer of a 1955 warrant for her arrest gave hope to Till’s family that justice might finally be served. But an aide to Mississippi Attorney General Lynn Fitch last month boldly said there was no new evidence to justify her arrest, and it was announced Tuesday that a grand jury had declined to indict her.In the years following Till’s death, Donham married twice, took classes at Delta State University and made jewelry that she sold at arts and crafts shows. She popped up on Facebook under an assumed name, tended to her dogs and lived a life devoid of one notable thing: punishment.But the debate about whether or not the facts compel her indictment is actually the sideshow; on the main stage is a much harder question: What does it say about us — not her — that she has escaped justice?At the time of Till’s death, the Leflore County, Mississippi, sheriff told reporters he did not want to “bother” Donham because she had two young children to care for. Today, she’s in her late 80s, and it can seem like the time for incarcerating her has passed.But justice demands accountability in whatever time is left. This principle has guided America’s policy in extraditing elderly Holocaust perpetrators back to Europe in the belief that they must pay for their crimes however possible — that if the only punishment left to be meted out is the denial of freedom in old age, than that’s the sentence that must be delivered.

Aug. 10, 202201:43

There is a division within the Department of Justice set up to root out in the U.S. participants at any level in the European Holocaust for prosecution. I am intimate with this work: I ran a division at the Justice Department that supported it and pushed for legislation for compensation for Holocaust victims. And that work inspired me to commit to bring similar focus and energy to analogous cases of civil rights murder, including volunteering to help members of the Till family and their supporters draw attention to the history.In one example of the prosecutions of Nazis, America extracted a 95-year-old from his home and medevaced him to Germany for lying on his immigration form when he entered the U.S. There was no bureaucratic concern about statutes of limitations on perjury; there was no plea for compassion because of the reach of time, frailty or the possible pressure that these young people endured by Nazi commanders.I’m proud of this work. The Justice Department’s long-term effort to root out those who supported Germany’s state genocide is among America’s strongest examples of its defense of human and civil rights. And the principle behind it is not retribution but an aspect of declaring “never again”: the forward-looking value that teaches people that this evil, even when carried out by the foot soldiers, cannot be pardoned or explained away.J.W. Milam, left; his wife, second left; Roy Bryant, far right; and his wife, Carolyn Bryant, in a courtroom in Sumner, Miss., on Sept. 23, 1955.AP We are not applying this same effort to punishing the white women who played a crucial role in sending Black men to their deaths, however. Donham set in motion the events that led to Till’s ghastly demise. Donham told the court that “this n----- man” had grabbed her hand at the cash register and said, “How about a date, baby?” She testified that she turned around and that Till then, from behind, put his left hand on her waist and his right arm on her hip and said, “What’s the matter baby, can’t you take it?” and uttered a vulgarity.

We are not applying this same effort to punishing the white women who played a crucial role in sending Black men to their deaths, however. Donham set in motion the events that led to Till’s ghastly demise. Donham told the court that “this n----- man” had grabbed her hand at the cash register and said, “How about a date, baby?” She testified that she turned around and that Till then, from behind, put his left hand on her waist and his right arm on her hip and said, “What’s the matter baby, can’t you take it?” and uttered a vulgarity.

But she later said that never happened. Till’s cousins, also teens and present at the time, said that at most he whistled at her, and even that is disputed by others at the scene. Her husband and brother-in-law were acquitted by the jury of their peers after just over an hour of deliberation. Donham did not even have to face that trifling consequence.Yet she is as responsible as her husband and kin who bludgeoned the boy to death. Our prisons are filled with Black men (and women) who participated in far less depraved crimes, but we do not have a culture that protects them. To find Donham guilty, though, would mean admitting a terrible flaw in our own culture.After public pressure, in 2006 a local prosecutor in Leflore County, Mississippi, had a grand jury consider bringing manslaughter charges against her at the conclusion of an FBI investigation that had led nowhere. The grand jury found insufficient evidence, however, so there were no charges.After the author Tim Tyson revealed in his 2017 book “The Blood of Emmett Till” that Donham had recanted her testimony, Attorney General Jeff Sessions had the Justice Department reopen the matter to see whether there was any way the federal government could intervene. That, too, fizzled. And this week, again, it was the same story.To be clear, this is not a failure of will of the prosecutors. ***This is a cultural failure***.In 2018 Sessions praised the work of the Justice Department’s best-known Nazi hunter, Eli Rosenbaum, and his team for successfully removing the 68th Nazi from the U.S. The passage of time did not deter the department from fulfilling its moral imperative of seeking justice for the victims of the Holocaust.Yet in 2022, in the case of Emmett Till, we hear the silence and our own nation’s complicity. In Western Europe, the mechanisms of the state, civil society and culture are conducting an inquiry into the past and its key perpetrators. In the U.S., we are not owning up to these chronic monstrosities nor holding enough among us accountable.

Once Scarpa arrived in Mississippi, local agents allegedly provided him with a gun and money to pay for information. Scarpa and an agent allegedly pistol-whipped and kidnapped Lawrence Byrd, a TV salesman and secret Klansman, from his store in Laurel and took him to Camp Shelby, a local Army base. At Shelby, Scarpa severely beat Byrd and stuck a gun barrel down his throat. Byrd finally revealed to Scarpa the location of the three men's bodies.[39][40] The FBI has never officially confirmed the Scarpa story. Though not necessarily contradicting the claim of Scarpa's involvement in the matter, investigative journalist Jerry Mitchell and Illinois high school teacher Barry Bradford claimed that Mississippi highway patrolman Maynard King provided the grave locations to FBI agent Joseph Sullivan after obtaining the information from an anonymous third party. In January 1966, Scarpa allegedly helped the FBI a second time in Mississippi on the murder case of Vernon Dahmer, killed in a fire set by the Klan.

n the summer of 1964, according to Linda Schiro and other sources, FBI field agents in Mississippi recruited the mafia captain Gregory Scarpa to help them find the missing civil rights workers.[38] The FBI was convinced the three men had been murdered, but could not find their bodies. The agents thought that Scarpa, using illegal interrogation techniques not available to agents, might succeed at gaining this information from suspects. Once Scarpa arrived in Mississippi, local agents allegedly provided him with a gun and money to pay for information. Scarpa and an agent allegedly pistol-whipped and kidnapped Lawrence Byrd, a TV salesman and secret Klansman, from his store in Laurel and took him to Camp Shelby, a local Army base. At Shelby, Scarpa severely beat Byrd and stuck a gun barrel down his throat. Byrd finally revealed to Scarpa the location of the three men's bodies.[39][40] The FBI has never officially confirmed the Scarpa story.

Though not necessarily contradicting the claim of Scarpa's involvement in the matter, investigative journalist Jerry Mitchell and Illinois high school teacher Barry Bradford claimed that Mississippi highway patrolman Maynard King provided the grave locations to FBI agent Joseph Sullivan after obtaining the information from an anonymous third party. In January 1966, Scarpa allegedly helped the FBI a second time in Mississippi on the murder case of Vernon Dahmer, killed in a fire set by the Klan. After this second trip, Scarpa and the FBI had a sharp disagreement about his reward for these services. The FBI then dropped Scarpa as a confidential informant.[41]

PLEASE tell me you’re being sarcastic about the good old days of J. Edgar Hoover - unless you mean in comparison to today.THought I knew most everything about the Mississippi murders -- but never heard THIS part. And it's VERY interesting that the problematic history of the FBI plays a key role here. Like it's connected DIRECTLY to the recent actions of FBI today.

Seems like the FBI and authorities up to Lyndon Johnson NEEDED to recruit the freakin' MAFIA to make the case. And the story of the violent abduction of the witness AND TORTURE -- that this mafioso MAY have applied to GET the location of the bodies -- CONVENIENTLY -- wouldn't allow that evidence to appear in a Courtroom.

How bizarre is that? Likely the FBI were not PRESENT during the interrogation (plausible deniability) -- so there was NO WITNESS as to the graves that could reliably testify. So they had to find another way.

OH -- how convenient. This Highway Patrol agent passed on the grave locations -- from -- AN ANONYMOUS third party. Which is never known to anyone. Wanna place bets the grave locations came from letting a mafioso shove a revolver barrel down the throat of a witness???

So AGAIN -- When you hear that "We're Federal agents and we're here to help" there's a VERY LONG history of Civil Liberties and Civil Rights abuses and downright dirty deeds behind the CURRENT mistrust of an FBI that yearns for the good ole days of J. Edgar Hoover who their Main Offices are named for.