Disir

Platinum Member

- Sep 30, 2011

- 28,003

- 9,611

- 910

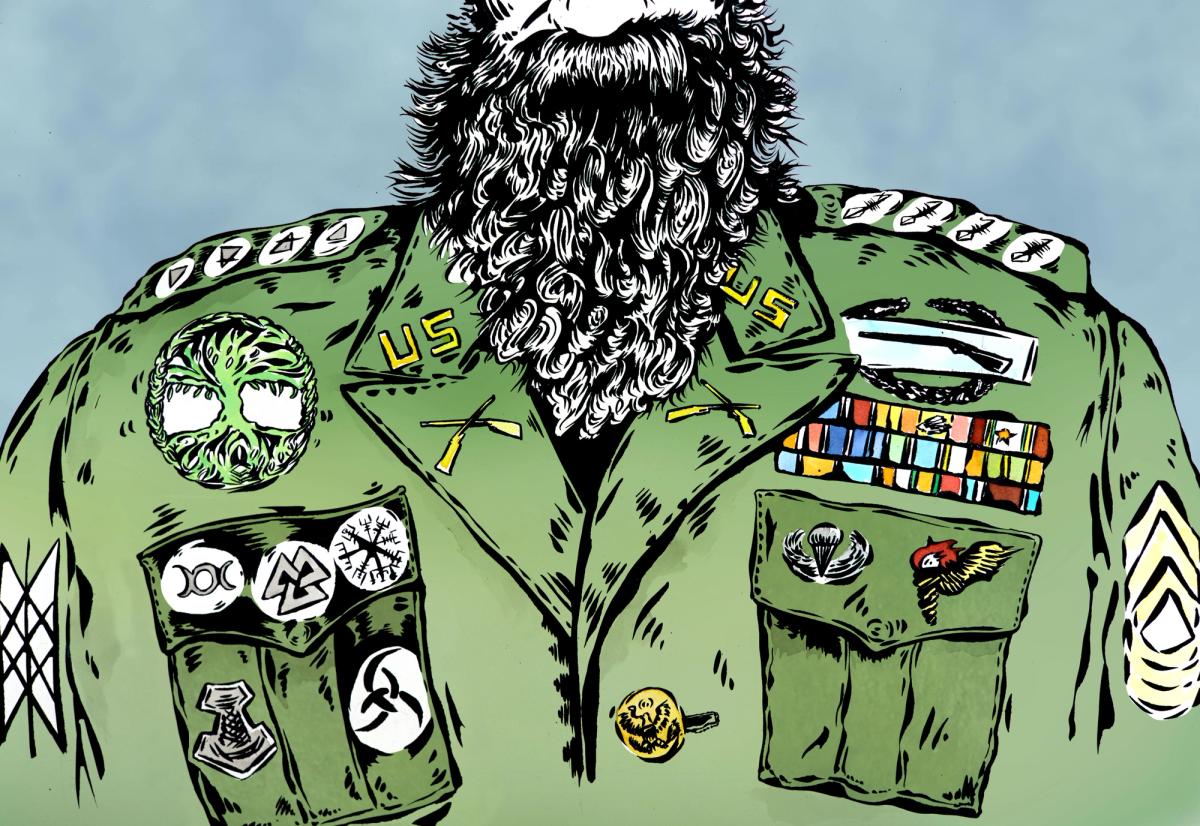

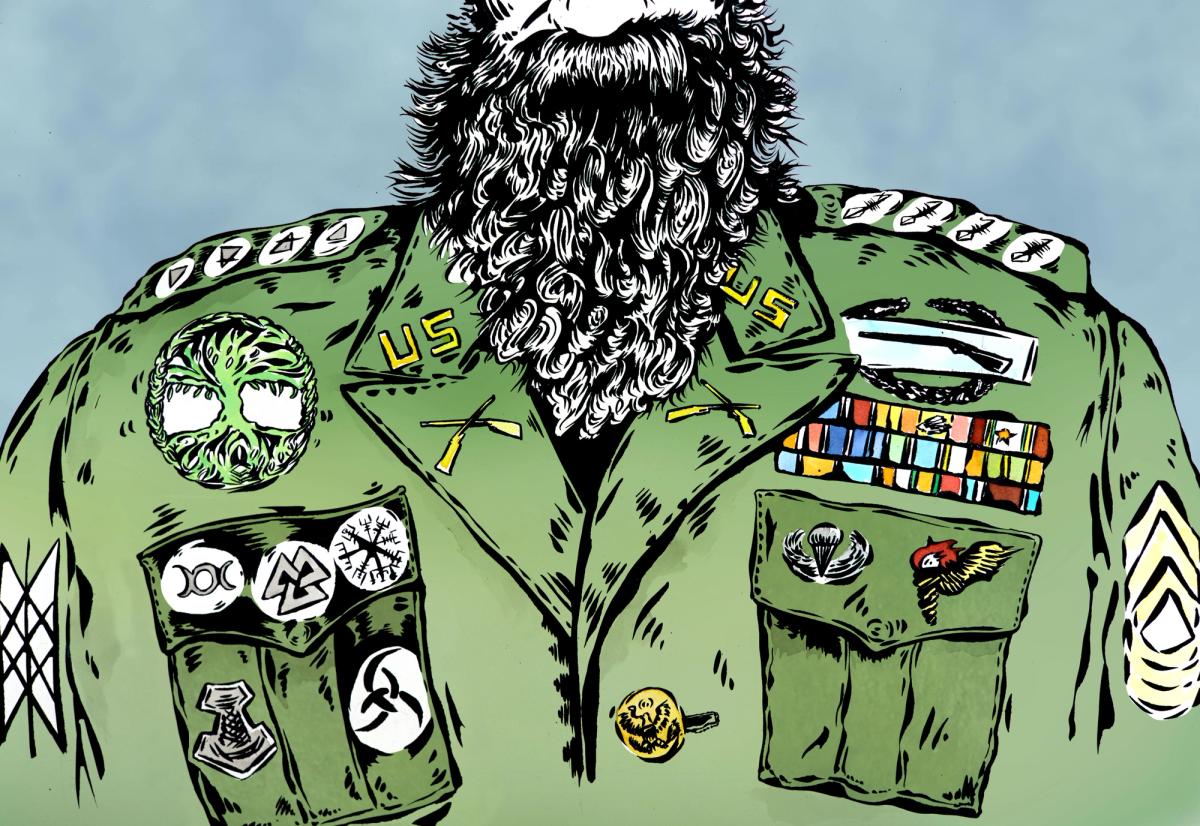

In Linden, North Carolina, a former Methodist church made local news when it became a meeting place for members of the white supremacist Asatru Folk Assembly, who define their movement as an “expression of the native, pre-Christian spirituality of Europe.” Just 30 minutes away at Fort Bragg, pagans in uniform—who adhere to Department of Defense-recognized old Norse pre-Christian beliefs—are eager to let you know that they aren’t affiliated. With the nation on alert for white supremacist threats and extremism in the military, practitioners of Norse paganism within the military are working to correct what they see as mischaracterizations and harmful associations surrounding their faith.

Aside from the Norse thunder god Thor’s portrayal as a benevolent goof in the Marvel cinematic universe, Norse paganism and mythology are most often linked in the American popular imagination with white supremacist ideologies. When the Robert Eggers Viking historical fiction film The Northman was released earlier this year, various media outlets responded to a Guardian piece, which quoted a couple of racist 4Chan posts in support of the film, and speculated about its popularity with white supremacists who co-opt symbols from Norse mythology. In 2019, the film Midsommar depicted Scandinavian pagans as smiling Aryans who love traditional folkways and nature, but not, it would seem, immigrants. (“Stop mass immigration to Halsingland” reads a highway banner near the rural commune where the fair-haired cultists in the film make their home.) Their reverence for Norse runes is perhaps matched only by their enthusiasm for flaying or burning people alive. In the real world, pre-Christian Norse symbols appeared in the 20th century in Third Reich art and heraldry, and in more recent history, on banners and clothing at the Charlottesville “Unite the Right” rally in 2017, on the Christchurch mosque shooter’s tactical gear in 2019, and most recently, in the Buffalo shooter’s manifesto.

www.tabletmag.com

www.tabletmag.com

There has been such a push back to make sure that people are aware that there is no connection with white supremacist groups.

Aside from the Norse thunder god Thor’s portrayal as a benevolent goof in the Marvel cinematic universe, Norse paganism and mythology are most often linked in the American popular imagination with white supremacist ideologies. When the Robert Eggers Viking historical fiction film The Northman was released earlier this year, various media outlets responded to a Guardian piece, which quoted a couple of racist 4Chan posts in support of the film, and speculated about its popularity with white supremacists who co-opt symbols from Norse mythology. In 2019, the film Midsommar depicted Scandinavian pagans as smiling Aryans who love traditional folkways and nature, but not, it would seem, immigrants. (“Stop mass immigration to Halsingland” reads a highway banner near the rural commune where the fair-haired cultists in the film make their home.) Their reverence for Norse runes is perhaps matched only by their enthusiasm for flaying or burning people alive. In the real world, pre-Christian Norse symbols appeared in the 20th century in Third Reich art and heraldry, and in more recent history, on banners and clothing at the Charlottesville “Unite the Right” rally in 2017, on the Christchurch mosque shooter’s tactical gear in 2019, and most recently, in the Buffalo shooter’s manifesto.

Pagans in Uniform

Media reports on followers of old Norse paganism focus on reactionary followers with white supremacist beliefs. But practitioners of the faith in the military are trying to correct the record.

There has been such a push back to make sure that people are aware that there is no connection with white supremacist groups.