320 Years of History

Gold Member

To reshore or not to reshore? Nearly half of the U.S. manufacturing companies we surveyed would consider reshoring at least part of their operations by 2020 (figure 10). Reasons for considering reshoring include favorable local logistics and supply chains, diminishing cost structure differential, and increase in domestic demand.

Increasingly, manufacturers are finding the financial incentives previously driving offshoring are diminishing. The wage differential is rapidly decreasing between developed and developing countries.

For example, China’s wages have increased at a compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) of 17 percent from 2001 to 2013. Likewise, wages in India have increased at an annual rate of 20 percent during the same period. On the other hand, wages in the U.S. grew by only 3 percent. When the decreasing wage differential is combined with the “hidden costs” of offshoring such as duty, freight, packaging, carrying cost of inventory, added supply chain complexity, as well as the potential innovation impact of separating engineering from manufacturing, U.S. manufacturing companies find it increasingly favorable to reshore operations back to America. Proximity between R&D and production functions greatly benefits manufacturing companies through streamlining processes, reducing product development time and cutting intangible costs. Thus, the case is mounting for manufacturers to bring back operations, as well as jobs, to America as long as they can find the workers.

The challenges of reshoring are potentially less obvious, but equally real. Companies that have already reshored have faced hurdles in stabilizing the new workforce, addressing the organizational skills gap, localizing the supply chain, altering the capital to labor ratio, and contemplating product design.

Given almost half of executives would consider reshoring their manufacturing operations back to U.S., demand for skilled workers is likely to further increase. Difficulties in finding the qualified talent may push manufacturers to automate their factories and replace people with machines. However, automation requires highly skilled personnel to operate, though fewer in number. In both cases (i.e., whether companies automate or not), manufacturers require skilled workers in their plants. Therefore, it is in the best interests of manufacturers and government to continue to invest in skills development programs that mitigate this challenging issue.

If one advocates for public policy aimed at "forcing" companies to reshore their manufacturing operations because one thinks that their doing so will make available the jobs that factory workers in China, Mexico and other places perform, one will be greatly disappointed. The blue text above is why.

I have little doubt that manufacturers will reshore their operations. I am equally certain that absent massive training of the American workforce, their doing so will not result in greater levels of "full" employment in the U.S., that is, underemployment in the sense of folks having to perform jobs that do not pay the wage they want to earn for their labor.

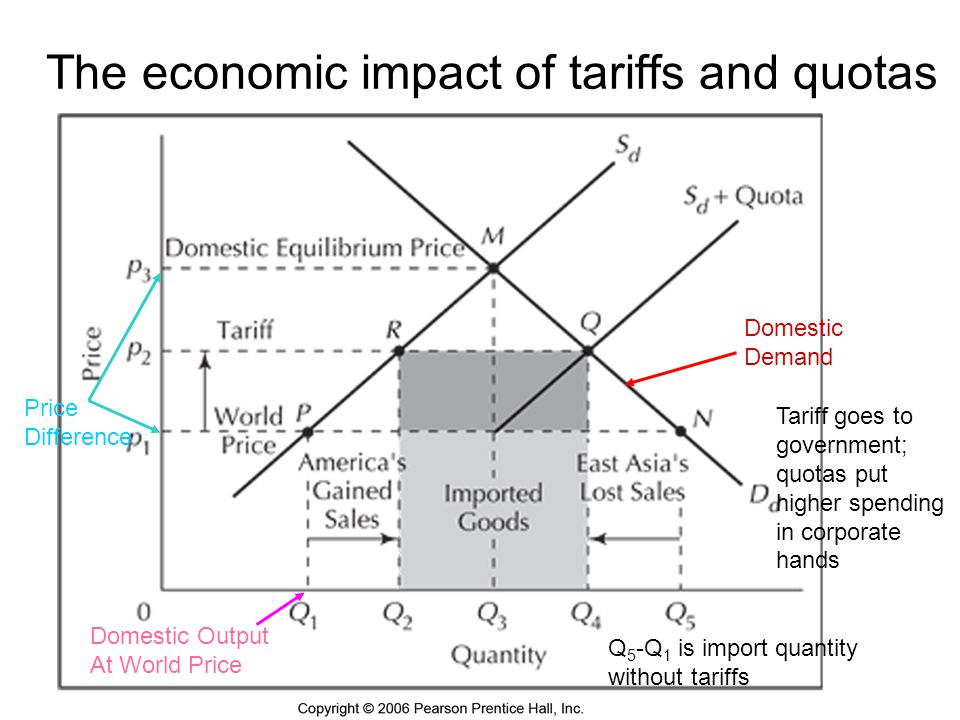

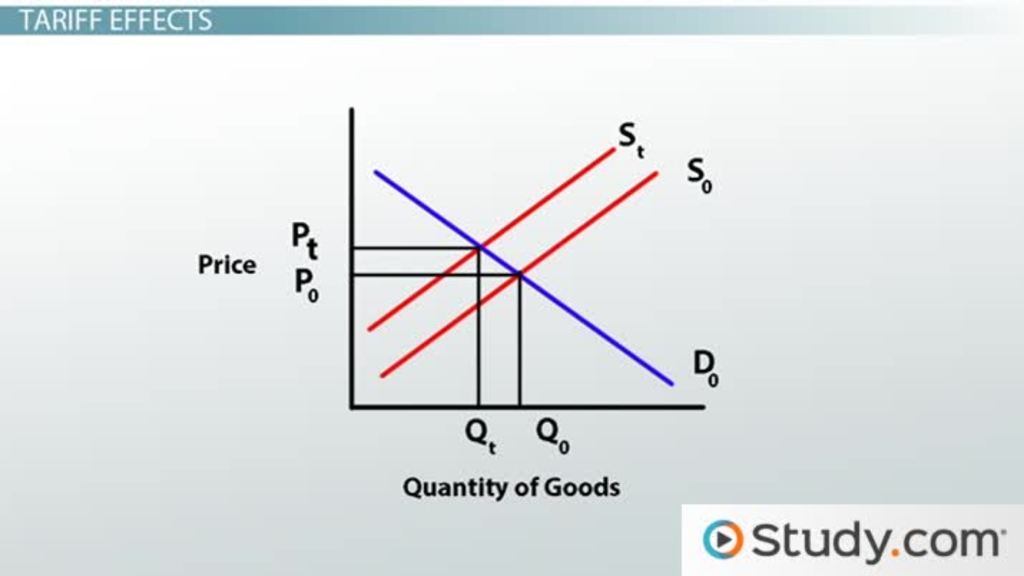

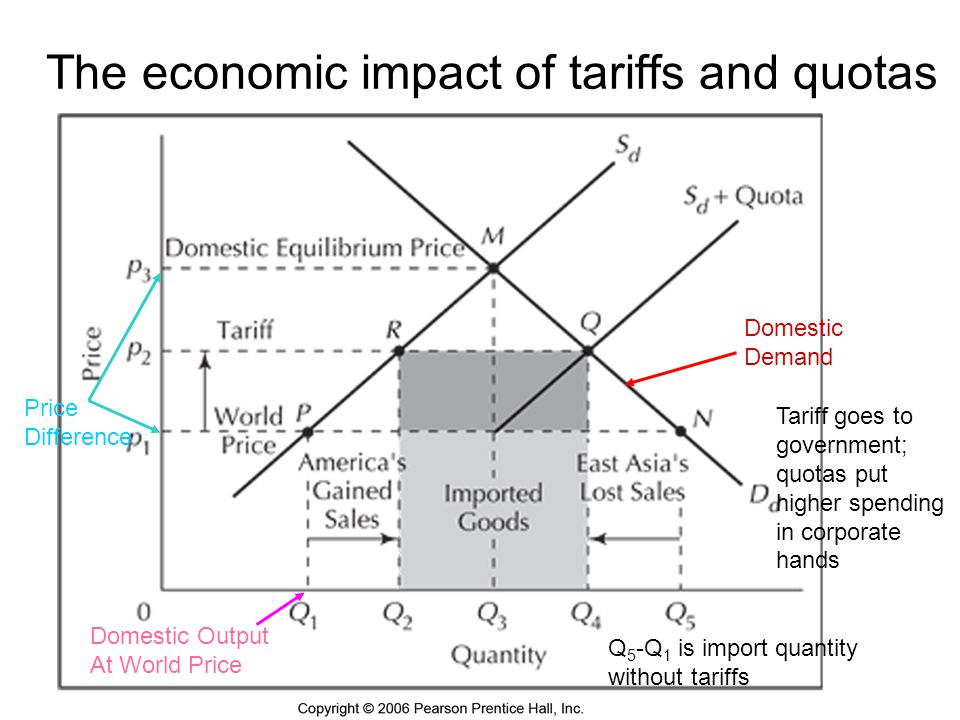

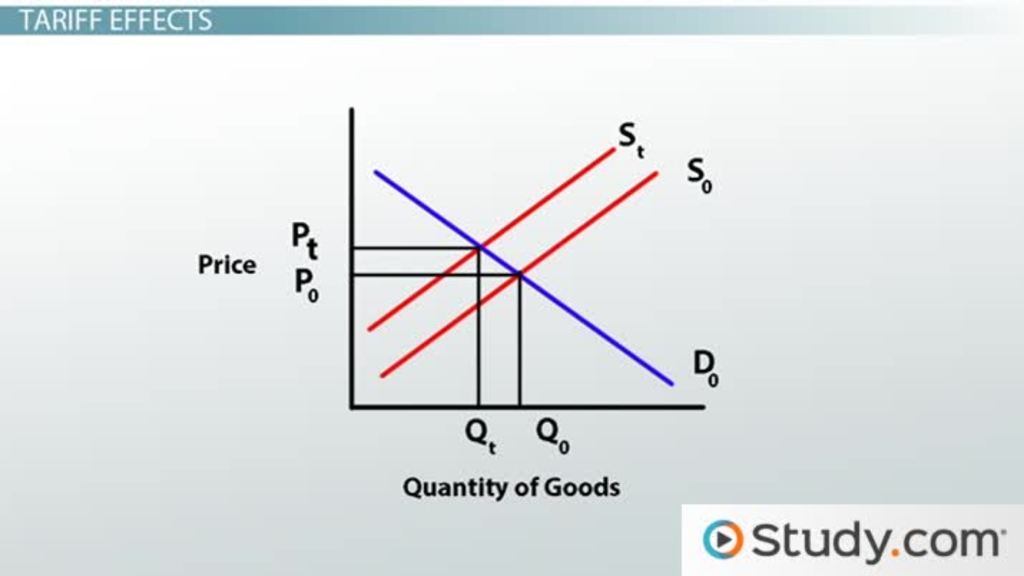

We currently have politicians advocating for tariffs and tax solutions as a way to boost employment. Unless they are also going to commit to using the tariff monies collected to fund massive skills development initiatives, I don't support the idea of tariffs at all. It's well understood that tariffs diminish consumer surplus and increase producer surplus. That's good for producers and bad for consumers and society as a whole.

Impact of Tariffs alone

What good is there to come for under-/unemployed workers when manufacturers/producers return and implement capital rather than labor to produce their goods? None. Workers remain under-/unemployed and prices are higher as a result of the tariff.

Increasingly, manufacturers are finding the financial incentives previously driving offshoring are diminishing. The wage differential is rapidly decreasing between developed and developing countries.

For example, China’s wages have increased at a compounded annual growth rate (CAGR) of 17 percent from 2001 to 2013. Likewise, wages in India have increased at an annual rate of 20 percent during the same period. On the other hand, wages in the U.S. grew by only 3 percent. When the decreasing wage differential is combined with the “hidden costs” of offshoring such as duty, freight, packaging, carrying cost of inventory, added supply chain complexity, as well as the potential innovation impact of separating engineering from manufacturing, U.S. manufacturing companies find it increasingly favorable to reshore operations back to America. Proximity between R&D and production functions greatly benefits manufacturing companies through streamlining processes, reducing product development time and cutting intangible costs. Thus, the case is mounting for manufacturers to bring back operations, as well as jobs, to America as long as they can find the workers.

The challenges of reshoring are potentially less obvious, but equally real. Companies that have already reshored have faced hurdles in stabilizing the new workforce, addressing the organizational skills gap, localizing the supply chain, altering the capital to labor ratio, and contemplating product design.

Given almost half of executives would consider reshoring their manufacturing operations back to U.S., demand for skilled workers is likely to further increase. Difficulties in finding the qualified talent may push manufacturers to automate their factories and replace people with machines. However, automation requires highly skilled personnel to operate, though fewer in number. In both cases (i.e., whether companies automate or not), manufacturers require skilled workers in their plants. Therefore, it is in the best interests of manufacturers and government to continue to invest in skills development programs that mitigate this challenging issue.

If one advocates for public policy aimed at "forcing" companies to reshore their manufacturing operations because one thinks that their doing so will make available the jobs that factory workers in China, Mexico and other places perform, one will be greatly disappointed. The blue text above is why.

I have little doubt that manufacturers will reshore their operations. I am equally certain that absent massive training of the American workforce, their doing so will not result in greater levels of "full" employment in the U.S., that is, underemployment in the sense of folks having to perform jobs that do not pay the wage they want to earn for their labor.

We currently have politicians advocating for tariffs and tax solutions as a way to boost employment. Unless they are also going to commit to using the tariff monies collected to fund massive skills development initiatives, I don't support the idea of tariffs at all. It's well understood that tariffs diminish consumer surplus and increase producer surplus. That's good for producers and bad for consumers and society as a whole.

Impact of Tariffs alone

What good is there to come for under-/unemployed workers when manufacturers/producers return and implement capital rather than labor to produce their goods? None. Workers remain under-/unemployed and prices are higher as a result of the tariff.

Last edited: