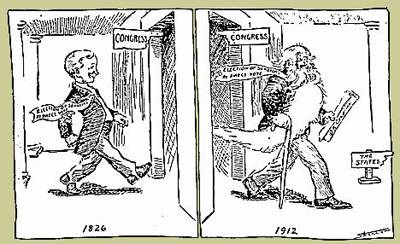

320 Years of History

Gold Member

Folks are grumbling about Ted Cruz having collected all of Colorado's delegates. This even as Wyoming has a similar process -- choose delegates in an election --> have the candidates lobby them for support --> hold a convention for the purpose of assigning the delegates voted for to the various candidates.

And what is Trump doing in Wyoming? Apparently nothing; he's essentially ceding them to Mr. Cruz, throwing in the towel. Really? He's just going to substantively cede the delegates to Mr. Cruz...even though he and his team must know that getting them, however many or few, helps achieve his objective of winning the GOP nomination. Trump isn't even going to attempt to give Wyoming's delegates a reason to support him.

Mark my words. I bet he'll next week be ranting about how Wyoming voters were robbed or some such nonsense.

Wyoming and Colorado are not the only jurisdictions whereof Trump has tacitly attested to the irrelevance of the voters there. He allowed Mr. Rubio to win 10 of 19 of D.C.'s pledged delegates and Mr. Kasich got 9 of them. Trump got none and made no effort to get any either. He didn't even hold a campaign event in D.C., which with it's small quantity of registered Republicans (~27K) and proportionately large quantity of delegates (D.C. population = ~500K and D.C. has 19 delegates; Florida population = ~20M and has 99 delegates, for example), could have been a "low effort for high 'profit' margin" endeavor for Trump, especially with his penchant/strategy of hosting huge rallies.

That's at least three places, having a total of 75 delegates among them, where Trump has all but abdicated to his competitors, yet, he claims the system is rigged. Cry me a river, Trump.

And what is Trump doing in Wyoming? Apparently nothing; he's essentially ceding them to Mr. Cruz, throwing in the towel. Really? He's just going to substantively cede the delegates to Mr. Cruz...even though he and his team must know that getting them, however many or few, helps achieve his objective of winning the GOP nomination. Trump isn't even going to attempt to give Wyoming's delegates a reason to support him.

Mark my words. I bet he'll next week be ranting about how Wyoming voters were robbed or some such nonsense.

Wyoming and Colorado are not the only jurisdictions whereof Trump has tacitly attested to the irrelevance of the voters there. He allowed Mr. Rubio to win 10 of 19 of D.C.'s pledged delegates and Mr. Kasich got 9 of them. Trump got none and made no effort to get any either. He didn't even hold a campaign event in D.C., which with it's small quantity of registered Republicans (~27K) and proportionately large quantity of delegates (D.C. population = ~500K and D.C. has 19 delegates; Florida population = ~20M and has 99 delegates, for example), could have been a "low effort for high 'profit' margin" endeavor for Trump, especially with his penchant/strategy of hosting huge rallies.

That's at least three places, having a total of 75 delegates among them, where Trump has all but abdicated to his competitors, yet, he claims the system is rigged. Cry me a river, Trump.