Missing Reality: The Diary Revealed Tap in the Holocaust of North African Jews

Parts of a diary written in a concentration camp in Libya and put mold in a closet in Holon were found, deciphered and translated. An important contribution to the recognition of North African Jews as Holocaust survivors

Thanks in no small part to Yossi Sokrei's successful novel, "Benghazi-Bergen-Belsen" (Am Oved, 2013) and the interviews conducted with him, many Israelis were exposed to the long silence surrounding the Holocaust of Libyan and North African Jews. Sokeri's book helped shatter the erroneous myth that it was solely the Holocaust of European Jewry, in other words, an almost exclusive Ashkenazi tragedy.

Sokeri's book was also preceded by studies, including that of the historian Yaakov Hajaj-Liluf, a display dedicated to North African Jewry at the Yad Vashem Museum, and three documentaries screened in Israel eight years earlier: "The Unknown Holocaust of North African Jews" directed by Yifat Kedar, "From Tripoli to Bergen-Belsen", a film by Marco Carmel, and "A Common Fate" directed by Serge Ankry.

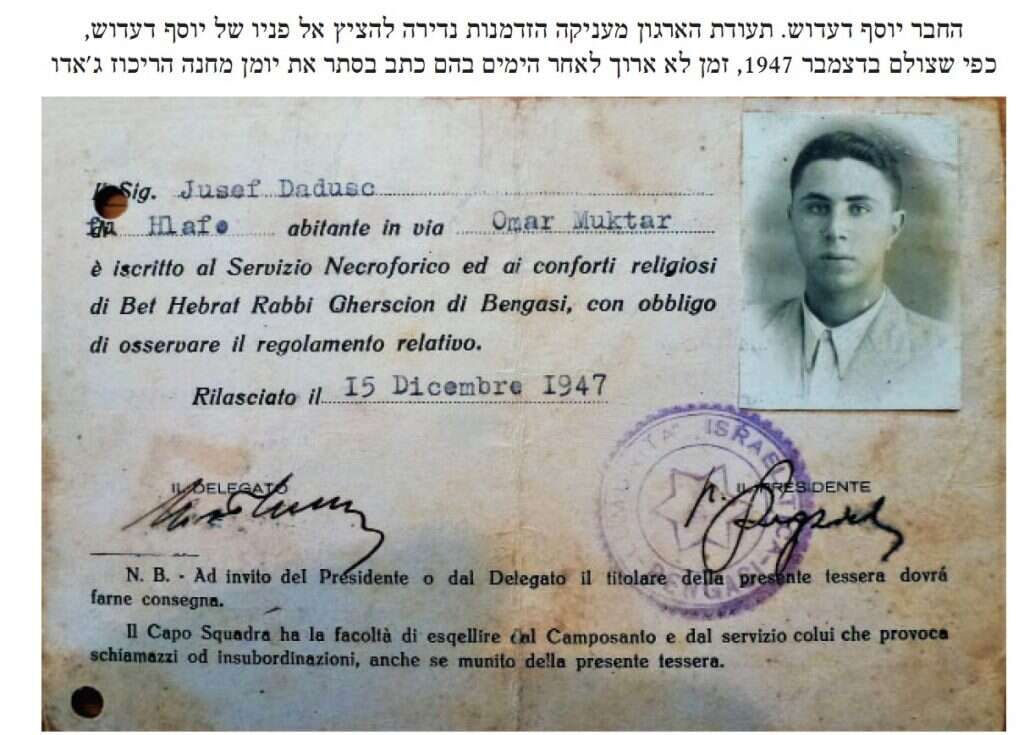

Journalist Shlomo Abramovich's new book on Libyan Jewry during World War II is now being published, including the diary of Yosef Dadush, written while he was a prisoner in the Jado concentration camp, where 2,600 Jews were imprisoned for more than a year. The diary, which had been stored for 75 years, was secretly written in Italian, in a kind of encrypted writing (dense lines and connected letters written in pencil in a notebook of absorbent paper), all in order to make it difficult for camp guards to decipher if caught. But all this later made it difficult for his son, Shimon Doron, to find the diary hidden in the closet. It would be several years before a savior came to him in the person of Dr. Yaakov Lats, a former lecturer at Bar-Ilan University and an expert on ancient Italian writings, who succeeded, after completing a Sisyphean translation work, in translating the part of the surviving diary into Hebrew.

Dadush never tried to recover the diary and publish it, thus trying to become a kind of Anne Frank of Libyan Jewry. Instead, he imprisoned him in a closet at his home in Holon, where he settled after immigrating to Israel in 1949, where the diary raised mold until it was partially erased. The question of why such an important and authentic diary, written in the midst of the tragic occurrence and allowing a rare glimpse into the harsh realities of the concentration camp, has been stored for so many years is troubling. Perhaps Dadush despaired of the alienating attitude of the representatives of the institutions in the country, who repeatedly repulsed his appeals to them so that they would finally recognize the Holocaust of Libyan Jewry. And perhaps he himself did not understand the magnitude of the value of the diary, though he later used to lecture on the subject.

Abramovich testifies that such a diary is in fact the dream of every historian. This is indeed a historical document, documenting not only the personal distress of the prisoner Yosef Dadush but also the plight of the camp inmates. In his book, Abramovich tells the story of the experiences of Libyan Jews at the time, and anyone who reads the diary and the book will no longer doubt that the Jews of North Africa were also victims of the Nazis.

(Yosef Dadush in an official document from 1947, not long after the diary was written)

Holocaust of the Jews in Lybia

33,000 Jews lived in Libya at the outbreak of World War II, and they lived in several cities of the country, which had been under Italian control since 1911. When the Duchess Benito Mussolini came to power in Italy, Libya's Jews were not initially in danger. Mussolini even once visited the Jewish Quarter in Tripoli and pledged to the Jews to respect their tradition. The Italian governor of Libya, Marshal Italo Bravo, also saw the Jews as a "positive element" in his words, but since they belonged to an established middle class and were an important factor in the country's economy, they were obliged to open their businesses on Saturdays and holidays.

Later, when Mussolini tightened his alliance with Hitler and even finally joined the axis of evil, the status of Jews also changed for the worse in the Italian colonies in Africa, including Libya, and they were subject to racial laws. Their rights were curtailed and some of their property was confiscated. In February 1942, Mussolini succumbed to Hitler's pressure and ordered what he called a "dilution of the Jewish population on the front lines." The Jews of the Kyrenia district near the border with Egypt, which was controlled by the British army, were transferred to the Jado concentration camp, a former military barracks.

The transfer of the Jews to the concentration camp and their imprisonment there for 13 months, was the culmination of a drama in several systems, in which the district passed suits from Italian control and the Nazis to British control, who captured it from their hands and returned again and again. The Jews of Kyrenia became a kind of game ball in the war between the powers, moving between hope and despair. The Nazis pressured the Italians to send the Jews to Europe, as they planned to kill them as part of the final solution. Only the British occupation actually saved them from extermination, as happened to many Jewish communities in Europe. The fact that Palestine Jews served in the British army also played in their favor in the upheavals in the province of Kyrenia during the war.

The bombing from the air intensified, the homes of many Jews were destroyed by bombing, and when control of this area returned for the third time to Rommel's army, Hitler insisted and the Italians sent hundreds of Jews to Italy, from where they were transferred to two concentration camps, Bergen-Belsen and Innsbruck-Reichenau. 'Edo, when the Nazis expect that they too will be sent to Europe later.

Hunger, disease and forced labor

"In the Jado camp, people were not systematically destroyed, they were not put in kilns and they were not murdered in the showers," Abramovich writes, "and yet, the Jado camp turned out to be hell." So does Dadush in his diary, that Abramovich quotes from time to time and appears in full in the last part of the book, after the historical chapters, which sometimes suffer from repetitions. "Oh Jado… We have reached hell. A road with lots of ups and downs and a blazing and dazzling sun," Dadush writes, in his rich and picturesque language. "The camp is full of commanders and sub-commanders as well as managers who are unable to manage. They only know how to scream. We found hell on earth here (175)."

Dadush could have spared himself this hell, but he chose not to accept the privilege offered to him by a local employer, with whom he had worked faithfully for a long time. This offered him to save him from his fate and remove his name from the list of those destined for deportation. "To the place to which all my Jewish brethren go - I will also go (p. 14)," Dadush replied bravely. In the camp, Dadush became the leader of the Jewish prisoners, and even secretly documented all his pains and pains, the tragedies, hunger, suffering and the outbursts of harassment and violence they suffered, as well as rare and brief pauses of contentment, when the Italians allowed him to stage a play, "Saul and David" in which he played the main part.

Eighty Jewish families were gathered inside each of the camp pavilions, which was surrounded by concert halls. Each was given a narrow hell plot, within which she had to make ends meet. They lived in terrible overcrowding and terrible sanitary conditions, which later brought upon them the plague of disease. The food was bad, half a bun a day, a hundred grams of rice for two weeks, some sugar and oil. With that they had to for a week, unless they managed to purchase some groceries with the meager money they brought with them after hastily selling all their belongings before deportation. The men were taken during the day to forced labor, or required to clean up the camp. "All the pavilions participated in the hard work, crumbling the rocks in the mountain and tidying up the ground… I felt sad and frustrated because of the way of life, because every day the money runs out and we do not know when we will be released… Every morning we get up, pray… read some Psalms" (182).

The description of the spread of the typhus epidemic, which killed many Jews (562 Jews perished in total in the camp and for various reasons), is an indictment against the Italians. "The camp was quarantined because of the typhus epidemic. The nurses did not care about the patients. Ignore who fell ill and also who died. "Men who will make a minyan and accompany the dead. A man thinks to himself: Today it is not my turn to die, maybe tomorrow. Maybe soon (189)," Dadush writes in his diary.

Arab gangs kill survivors

Dadush eventually survived, but his toddler daughter Ada died of the plague. In a special and touching chapter he describes how he dug her grave with his own hands, while two Italian carabinieri smoke and chat. "I dug, prayed and cried, but mostly I apologized from the dead. Did I do everything I could to save her?" (24). For a moment, Dadush may have regretted rejecting the offer of his employer who wanted to do better with him. "Did he sentence his daughter Ada to that?" (25).

The British finally liberated the camp, and the prisoners returned to their homes and heard the terrible news that had come from Europe about the extermination of the Jews of their country in Bergen-Belsen. They were forced to suffer riots by Libyan Arabs, in which 133 Jews were murdered. Soldiers from Palestine managed to rescue 150 Jews, who were in danger of death, from the rioters.

Abramovich expands on the exciting encounter between the soldiers and the survivors. He also quotes from two books, those of Moshe Mosinson and Meshulam Riklis, who served as the driver of Rabbi Ephraim Elimelech Orbach, the rabbi of the Jews of the Middle East in the British army, describing such meetings, including the Passover Seder. The Israeli soldiers even helped Libyan Jews immigrate to Israel, also through fictitious marriages with Jewish young women.

Although the Jado camp was not a satanic planet like Auschwitz, it is still a hell that justifies historical documentation and recognition of Libyan Jews as Holocaust survivors. Abramovich writes in his opening remarks that "the research and exposure (of the diary; XI) is intended first and foremost for the younger generation" (15). A unique document that combines the personal and the historical.

(Translated from

Makor Rishon)

www.israellycool.com

www.israellycool.com