SobieskiSavedEurope

Gold Member

- Thread starter

- Banned

- #601

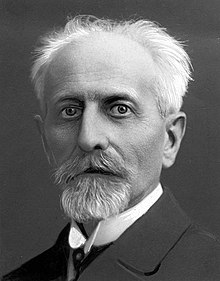

Julian Ochorowicz

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to navigationJump to search

Julian Ochorowicz

Julian Leopold Ochorowicz (['juljan lɛˈɔpɔld ɔxɔˈrɔvit͡ʂ]; outside Poland also known as Julien Ochorowitz; Radzymin, 23 February 1850 – 1 May 1917, Warsaw) was a Polish philosopher, psychologist, inventor (precursor of radio and television[1]), poet, publicist, and leading exponent of Polish Positivism.

Contents

Life[edit]

Julian Ochorowicz was the son of Julian and Jadwiga, née Sumińska.

Ochorowicz studied natural sciences at Warsaw University, graduating in 1871. He subsequently studied at Leipzig University under Wilhelm Wundt; in 1874 he received his doctorate there with a thesis On Conditions of Consciousness.

Returning to Warsaw, in 1874-75 he was editor-in-chief of the popular Polish-language periodical, Niwa (The Field). From 1881 he was assistant professor(docent) of psychology and natural philosophy at Lwów University.

In 1882 he was sent to Paris, France, where he spent several years. Later, from 1907, he would be co-director of the Institut General Psychologique.

Returning to Warsaw, from 1900 Ochorowicz was president of Kasa Literacka (the Literary Fund). He published his pedagogical papers in Encyklopedia Wychowawcza (the Encyclopedia of Education).

Ochorowicz was a pioneer of empirical research in psychology and conducted studies into occultism, Spiritualism, hypnosis and telepathy. His most popular works included Wstęp i pogląd ogólny na filozofię pozytywną (An Introduction to and Overview of Positive Philosophy, 1872) and Jak należy badać duszę? (How Should One Study the Soul?, 1869).

Ochorowicz the poet published in Przegląd Tygodniowy (the Weekly Review) under the pen-name Julian Mohort. He wrote the poem, "Naprzód" ("Forward," 1873), regarded as the Polish Positivists' manifesto.

Bolesław Prus

Ochorowicz, a trained philosopher with a doctorate from the University of Leipzig, became the leader of the Positivist movement in Poland. In 1872 he wrote: "We shall call a Positivist, anyone who bases assertions on verifiable evidence; who does not express himself categorically about doubtful things, and does not speak at all about those that are inaccessible."[2]

In 1877 he elaborated the theory for a monochromatic television, to be constructed as a screen comprising bulbs that would convert transmitted images into groups of light points.

In 1885, on several occasions, he demonstrated his own improved telephone. In Paris, he connected the building of the Ministry of Posts and Telegraph with the Paris Opera, 4 kilometers away. At the Antwerp World's Fair, he set up a connection with Brussels, 45 km distant. He linked St. Petersburg, Russia, with Bologoye, 320 km away.

He experimented with microphones and with apparatus for sending sound and light over distances, and so is regarded as a precursor of radio and television.

Ochorowicz conducted experiments at a psychological laboratory that he established at Wisła.

Prus[edit]

Eusapia Palladino, Warsaw, 1893

Psychologist Ochorowicz watches closely as Polish telekinetic Stanisława Tomczyk, in a trance, levitates scissors. Wisla, Poland, 1909.[3][4]

Monument to Ochorowicz at Wisła, which he built into a health resort and tourist destination

Julian Ochorowicz was a former Lublin secondary-school and Warsaw University schoolmate of Bolesław Prus, who portrayed him in his 1889 novel, The Doll, as the scientist "Julian Ochocki." Ochorowicz, after returning to Warsaw from Paris, in 1893 delivered several public lectures on ancient Egyptian knowledge. These evidently helped inspire Prus to write (1894–95) his sole historical novel, Pharaoh. Ochorowicz provided Prus books on Egyptology that he had brought back from Paris.[5]

Also in 1893, Ochorowicz introduced Prus to the Italian Spiritualist, Eusapia Palladino, whom he had brought to Warsaw from her mediumistic tour in St. Petersburg, Russia.[6] Prus attended a number of séances conducted by Palladino and incorporated several prominent spiritualist-inspired scenes into his 1895 novel Pharaoh.[7]

Ochorowicz hosted Palladino in Warsaw from November 1893 to January 1894. Regarding the phenomena demonstrated at Palladino's séances, he concluded against the spirit hypothesis and for a hypothesis that these phenomena were caused by a "fluidic action" and were performed at the expense of the medium's own powers and those of the other participants in the séances. Ochorowicz, with Frederic William Henry Myers, Charles Richet and Oliver Lodge, investigated Palladino in the summer of 1894 at Richet's house on the Île du Grand Ribaud in the Mediterranean. Myers and Richet claimed that furniture moved during the séances and that some of the phenomena were the result of a supernatural agency.[8] However, Richard Hodgson claimed there was inadequate control during the séances and that the precautions described did not rule out trickery. Hodgson wrote that all the phenomena "described could be accounted for on the assumption that Eusapia could get a hand or foot free." Lodge, Myers and Richet disagreed, but Hodgson was later proven correct in the Cambridge sittings as Palladino was observed to have used tricks exactly the way he had described them.[8]

After Ochorowicz's wife left him, he decided to make some changes in his life: he bought a piece of land at Wisła in Poland's mountains, built himself a villa as well as four additional houses for tourists, and proceeded to live on the rentals.[9]

About 20 June 1900, Prus and his household arrived to visit. In July Prus traveled to nearby Kraków, where until the beginning of September he underwent treatments for his multifarious medical complaints by an ophthalmologist, a neurologist, and a physician who treated his thyroid.[10]

In 1908–9, at Wisła, Ochorowicz studied the mediumship of Stanisława Tomczyk.

In the latter half of the 19th century, Spiritualism was not an unusual subject of study for noted psychologists. A prominent American psychologist who looked favorably on Spiritualism was William James.

Bibliography[edit]

Julian Ochorowicz - Wikipedia

From Wikipedia, the free encyclopedia

Jump to navigationJump to search

Julian Ochorowicz

Julian Leopold Ochorowicz (['juljan lɛˈɔpɔld ɔxɔˈrɔvit͡ʂ]; outside Poland also known as Julien Ochorowitz; Radzymin, 23 February 1850 – 1 May 1917, Warsaw) was a Polish philosopher, psychologist, inventor (precursor of radio and television[1]), poet, publicist, and leading exponent of Polish Positivism.

Contents

Life[edit]

Julian Ochorowicz was the son of Julian and Jadwiga, née Sumińska.

Ochorowicz studied natural sciences at Warsaw University, graduating in 1871. He subsequently studied at Leipzig University under Wilhelm Wundt; in 1874 he received his doctorate there with a thesis On Conditions of Consciousness.

Returning to Warsaw, in 1874-75 he was editor-in-chief of the popular Polish-language periodical, Niwa (The Field). From 1881 he was assistant professor(docent) of psychology and natural philosophy at Lwów University.

In 1882 he was sent to Paris, France, where he spent several years. Later, from 1907, he would be co-director of the Institut General Psychologique.

Returning to Warsaw, from 1900 Ochorowicz was president of Kasa Literacka (the Literary Fund). He published his pedagogical papers in Encyklopedia Wychowawcza (the Encyclopedia of Education).

Ochorowicz was a pioneer of empirical research in psychology and conducted studies into occultism, Spiritualism, hypnosis and telepathy. His most popular works included Wstęp i pogląd ogólny na filozofię pozytywną (An Introduction to and Overview of Positive Philosophy, 1872) and Jak należy badać duszę? (How Should One Study the Soul?, 1869).

Ochorowicz the poet published in Przegląd Tygodniowy (the Weekly Review) under the pen-name Julian Mohort. He wrote the poem, "Naprzód" ("Forward," 1873), regarded as the Polish Positivists' manifesto.

Bolesław Prus

Ochorowicz, a trained philosopher with a doctorate from the University of Leipzig, became the leader of the Positivist movement in Poland. In 1872 he wrote: "We shall call a Positivist, anyone who bases assertions on verifiable evidence; who does not express himself categorically about doubtful things, and does not speak at all about those that are inaccessible."[2]

In 1877 he elaborated the theory for a monochromatic television, to be constructed as a screen comprising bulbs that would convert transmitted images into groups of light points.

In 1885, on several occasions, he demonstrated his own improved telephone. In Paris, he connected the building of the Ministry of Posts and Telegraph with the Paris Opera, 4 kilometers away. At the Antwerp World's Fair, he set up a connection with Brussels, 45 km distant. He linked St. Petersburg, Russia, with Bologoye, 320 km away.

He experimented with microphones and with apparatus for sending sound and light over distances, and so is regarded as a precursor of radio and television.

Ochorowicz conducted experiments at a psychological laboratory that he established at Wisła.

Prus[edit]

Eusapia Palladino, Warsaw, 1893

Psychologist Ochorowicz watches closely as Polish telekinetic Stanisława Tomczyk, in a trance, levitates scissors. Wisla, Poland, 1909.[3][4]

Monument to Ochorowicz at Wisła, which he built into a health resort and tourist destination

Julian Ochorowicz was a former Lublin secondary-school and Warsaw University schoolmate of Bolesław Prus, who portrayed him in his 1889 novel, The Doll, as the scientist "Julian Ochocki." Ochorowicz, after returning to Warsaw from Paris, in 1893 delivered several public lectures on ancient Egyptian knowledge. These evidently helped inspire Prus to write (1894–95) his sole historical novel, Pharaoh. Ochorowicz provided Prus books on Egyptology that he had brought back from Paris.[5]

Also in 1893, Ochorowicz introduced Prus to the Italian Spiritualist, Eusapia Palladino, whom he had brought to Warsaw from her mediumistic tour in St. Petersburg, Russia.[6] Prus attended a number of séances conducted by Palladino and incorporated several prominent spiritualist-inspired scenes into his 1895 novel Pharaoh.[7]

Ochorowicz hosted Palladino in Warsaw from November 1893 to January 1894. Regarding the phenomena demonstrated at Palladino's séances, he concluded against the spirit hypothesis and for a hypothesis that these phenomena were caused by a "fluidic action" and were performed at the expense of the medium's own powers and those of the other participants in the séances. Ochorowicz, with Frederic William Henry Myers, Charles Richet and Oliver Lodge, investigated Palladino in the summer of 1894 at Richet's house on the Île du Grand Ribaud in the Mediterranean. Myers and Richet claimed that furniture moved during the séances and that some of the phenomena were the result of a supernatural agency.[8] However, Richard Hodgson claimed there was inadequate control during the séances and that the precautions described did not rule out trickery. Hodgson wrote that all the phenomena "described could be accounted for on the assumption that Eusapia could get a hand or foot free." Lodge, Myers and Richet disagreed, but Hodgson was later proven correct in the Cambridge sittings as Palladino was observed to have used tricks exactly the way he had described them.[8]

After Ochorowicz's wife left him, he decided to make some changes in his life: he bought a piece of land at Wisła in Poland's mountains, built himself a villa as well as four additional houses for tourists, and proceeded to live on the rentals.[9]

About 20 June 1900, Prus and his household arrived to visit. In July Prus traveled to nearby Kraków, where until the beginning of September he underwent treatments for his multifarious medical complaints by an ophthalmologist, a neurologist, and a physician who treated his thyroid.[10]

In 1908–9, at Wisła, Ochorowicz studied the mediumship of Stanisława Tomczyk.

In the latter half of the 19th century, Spiritualism was not an unusual subject of study for noted psychologists. A prominent American psychologist who looked favorably on Spiritualism was William James.

Bibliography[edit]

- Jak należy badać duszę? Czyli o metodzie badań psychologicznych (How Should One Study the Soul? On the Method of Psychological Studies), 1869.

- Miłość, zbrodnia, wiara i moralność. Kilka studiów z psychologii kryminalnej (Love, Crime, Faith and Morality: Several Studies in the Psychology of Crime), 1870.

- Wstęp i pogląd ogólny na filozofię pozytywną (An Introduction to and Overview of Positive Philosophy), 1872.

- Z dziennika psychologa (From a Psychologist's Journal), 1876.

- O twórczości poetyckiej ze stanowiska psychologii (On Poetic Creativity from the Standpoint of Psychology), 1877.

- De la Suggestion mentale, deuxieme édition (second edition), Paris, Doin, 1889.

- Psychologia, pedagogika, etyka. Przyczynki do usiłowań naszego odrodzenia narodowego (Psychology, Pedagogy, Ethics: Contributions toward Our National Rebirth), 1917.

Julian Ochorowicz - Wikipedia