SobieskiSavedEurope

Gold Member

- Thread starter

- Banned

- #581

Edited by Andrzej Grzybowski, MD, PhD

Edmund Biernacki (1866-1911): Discoverer of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate. On the 100th anniversary of his death

Author links open overlay panelAndrzejGrzybowskiMD, PhDabJarosławSakMD, PhDc

Redirecting

Abstract

In contemporary medicine, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is used to assess severity in patients with such diseases as erysipelas, psoriasis, eosinophilic fasciitis, dermatomyositis, and Behçet's disease. We remember the scientific achievements of a Polish physician, the discoverer of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), Edmund Faustyn Biernacki (1866-1911), on the 100th anniversary of his death. The practical application of ESR in clinical diagnostics in 1897 by Biernacki was little known for many years, because it was often neglected owing to the work of Robert Fåhraeus and Alf Westergren from 1921. In addition, it is also frequently omitted that before Westergren's and Fåhraeus's reports were published, ESR was also noticed by Ludwig Hirschfeld in 1917.

Introduction

The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is used to assess the acute phase response of many inflammatory diseases. Contemporary dermatology uses the ESR test for assessing disease severity in patients with erysipelas,1, 2, 3, 4 psoriasis,5, 6, 7 eosinophilic fasciitis,8 dermatomyositis,9 and Behçet's disease.10, 11, 12 An elevated ESR is used as a key diagnostic criterion for polymyalgia rheumatica13 and an independent predictor of giant cell arteritis.14

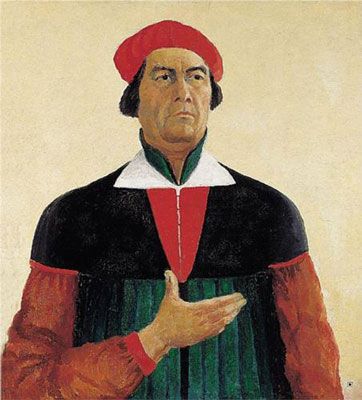

This year, 2011, marks the 100th anniversary of the death of Edmund Faustyn Biernacki (1866-1911), a Polish physician (Figure 1), who discovered the phenomenon of ESR.

Fig. 1

Biernacki was one of the representatives of the Polish school of philosophy of medicine15, 16 and the first scientist to use ESR17, 18 in medical diagnostics. Unfortunately, these historical facts are frequently omitted in the English language literature. It was only in the last decade of the 20th19century and the first decade of the 21st20, 21, 22, 23, 24 century that Biernacki's name has appeared. This appearance was connected to the presentation of the Polish school of philosophy of medicine and the discussion on the history of the discovery of ESR. Before this, Polish authors occasionally appealed to acknowledge Biernacki's input into the discovery of ESR.25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30 This probably contributed to the gradual “rehabilitation” of Biernacki's contribution to this discovery; however, incomplete information concerning the discovery of ESR, which omits Biernacki's input,31 still appears even in the most recent scientific reports.32, 33 Thus, on the 100-year anniversary of Biernacki's death, it is worthwhile to briefly introduce his life and major scientific accomplishments, especially compared with the short history of ESR.

Edmund Biernacki as a physician and philosopher of medicine

The life and professional activities of Edmund Faustyn Biernacki (1866-1911) (Figure 1) coincided with the period of Partitions of Poland. In the 19th century and almost the first 2 decades of the 20th century, the Polish people had no political autonomy while remaining under the Russian, German, and Austro-Hungarian occupation. Biernacki was born in the Russian partition on December 19, 1866, in the city of Opoczno. At the age of 18, he enrolled at the Medical Faculty of the Imperial University of Warsaw. He published his first scientific papers during his medical studies, and for one of them34he received a Gold Medal in a competition announced by the Faculty of Medicine.

After graduating in 1889, Biernacki worked as an assistant in the Therapeutic Department of the Imperial University of Warsaw. There, he published many papers in the field of gastroenterology, neurology, and metabolic disorders. In the following year, he received a scholarship from the Joseph Mianowski Fund35 to conduct research in foreign research centers. First, as an assistant, he held internships in the clinics of Wilhelm Heinrich Erb (1840-1921) and Johann Hoffmann (1857-1919) in Heidelberg, and Jean-Martin Charcot (1825-1893) in Paris.

As an independent researcher, he worked in Heidelberg, Paris, and Giessen. In Paris, under the tutelage of Georges Hayem (1841-1933), he devised methods of examining the gastric contents, and while staying in Giessen at Franz Riegel's (1843-1904) clinic, he examined the importance of saliva and oral digestive physiology in the pathophysiology of digestive processes occurring in the stomach.22, 27, 28 In subsequent years of his career, as the head of the Diagnostic Department of the Imperial University of Warsaw, he devoted much effort to research in the fields of neurology, cardiology, infectious diseases, and hematology. Studies in the field of hematology, which led him to the discovery of ESR, were conducted between 1893 and 1897.

The increasing russification of the Imperial University of Warsaw, including the university clinic, was probably the main factor that caused Biernacki to change his workplace.27 In July 1897, he became department head at the Wola Hospital in Warsaw, and during this period, his fascination with methodology of medical science and philosophy of medicine began. At the turn of the century, he published 3 books concerning these issues,36, 37, 38which presented a meta-analysis of the relationships between diagnostic and therapeutic possibilities of contemporary European medicine.

The fourth book, on the theory of health and illness,39 was published after his transfer to Lviv, which remained in the Austro-Hungarian annexation. This transfer was caused by economic reasons. Because Biernacki was held in high esteem by the Lviv medical environment, in December 1902, the Medical Faculty of the University of Lviv, in recognition of his work, abandoned the procedural nostrification of his diploma. It is essential to mention that during the Partition of Poland, physicians who changed their place of work by leaving for a different partition (occupation zone) were obligated to undergo such nostrification procedure.

In 1908, at the University of Lviv, Biernacki received a title of associate professor at the Department of General and Experimental Pathology. From Lviv, he often traveled to Carlsbad, where he ran a medical practice in a local spa. He died suddenly in Lviv on December 29, 1911, at the age of 45. Unfortunately, he did not live to see the Polish nation gain independence in 1918.

Despite his premature death, his scientific achievements were quite impressive, as he published 98 scientific papers, including experimental and theoretical ones,22, 28 almost all of which were published in both Polish and German. Biernacki's contributions appeared in 21 scientific German language journals. Apart from explaining the nature of ESR, he was also the discoverer of one of the clinical manifestations of tabes dorsalis. In neurology, this symptom, which manifests itself by the analgesia of the ulnar nerve, is called the Biernacki sign.28 At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, Biernacki was known in the world literature as an outstanding expert on metabolic disorders. In Norden's textbook, which concerned this issue, apart from many quotes, Biernacki was described as “Der recht kritische Biernacki” (“rightly critical Biernacki”).40

The discovery of ESR

Beginning in ancient times, bloodletting with which the sick were treated, made it possible to make empirical observations on the red blood clot as being covered with a layer of whitish fluid called “crusta phlogistica” or “crusta inflammatoria.”41 In modern times, a Scottish surgeon, John Hunter (1728-1793),21 and a German physician, Hermann Nasse (1807-1892), are believed to be the discoverers of the ESR. In this context, it is also worth mentioning the London physician, William Hewson (1739-1774), considered the “father of hematology,”42 as the first person who noticed that the separation of defibrinated blood occurs more slowly than in the case of undefibrinated blood43; however, the first person to explain this phenomenon by means of an experiment and to use it in clinical diagnostics was Edmund Faustyn Biernacki.17, 18, 22, 24, 25,27, 28, 29, 30,44 The explanation of ESR that was provided by Biernacki was based on proving a close relationship between the speed of sedimentation of red blood cells and the level of fibrinogen.17, 18 Simultaneously, in 1894, Biernacki published his first reports about ESR in the Proceedings of the Warsaw Medical Society,45Wiener Medicinische Wochenschrift,46 and Zeitschrift für physiologische Chemie47; however, he did not include the evaluation of its usefulness in medical diagnostics.

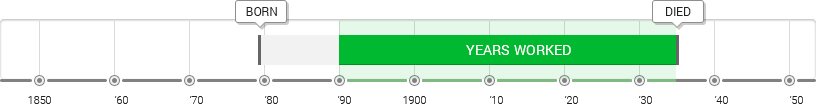

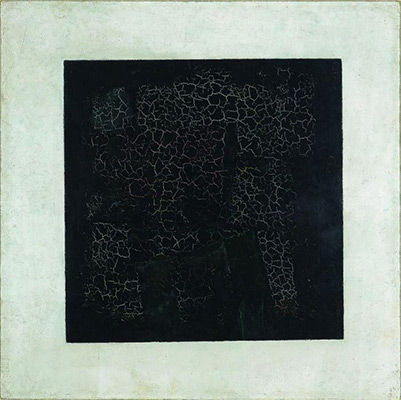

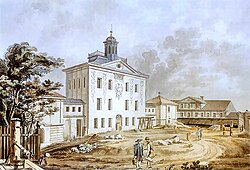

In 1897, Biernacki announced the diagnostic value of ESR together with a pathophysiological explanation of this phenomenon in 2 contributions: one written in Polish in Gazeta Lekarska17 (Figure 2) and the second in German in the Deutsche Medicinische Wochenschrift18 (Fig. 3, Fig. 4). Shortly before the publication of his works describing ESR, during a meeting of the Warsaw Medical Society on June 22, 1897, Biernacki presented the 5 most important conclusions from his observations.22, 28 Those conclusions were as follows: the blood sedimentation rate and volume of residue produced is different in different individuals; blood with small amounts of red blood cells sediments faster; blood sedimentation rate depends on the level of fibrinogen in the blood plasma; during the course of febrile diseases (rheumatic fever included) with large amounts of plasma fibrinogen, the ESR is increased; in defibrinated blood, the sedimentation process is slower.27 Biernacki's findings clearly proved the clinical importance of the discovery of ESR. They indicated the sedimentary features of the plasma fibrinogen, which occurs in increased amounts in febrile disease.

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

The application of ESR by Biernacki in clinical diagnostics was described in detail in 1902 in a textbook on blood pathology written by Gravitz.48 In 1906, Biernacki modified his method by using a capillary pipette of his own design, called a “microsedimentator,”22, 49 instead of the original glass cylinder (Figure 4). This technique allowed the measurement of ESR after sampling of the capillary blood from the tip of the finger. The reading of the results was possible after 60 minutes. As an anticoagulant, Biernacki used powdered sodium oxalate.

It is immensely interesting that 20 years after Biernacki's publication concerning ESR, 3 independent scientists made similar “discoveries.” Those scientists were Ludwik Hirszfeld (1884-1954), Robert Sanno Fåhraeus (1888-1968), and Alf Vilhelm Albertsson Westergren (1891-1968). First in 1917, 6 years after Biernacki's death, a Polish physician of Jewish origins, who later became famous for research on blood groups and the Rh factor, Ludwik Hirszfeld50, 51 presented a report on ESR. In blood taken from patients diagnosed with malaria, Hirszfeld observed the phenomenon of ESR.52 These observations were made during his stay in Serbia during an outbreak of malaria in 1917.

A year after Hirszfeld's report, a Swedish haematologist, Robert Sanno Fåhraeus, also announced his “discovery.” He analyzed the time differences of erythrocyte sedimentation occurring in 2 groups of women: pregnant and nonpregnant. He presented the results of his work in 1918,53 and 3 years later, he extensively discussed it in the journal Acta Medica Scandinavica.54Fåhraeus saw using ESR as a possible pregnancy test.

Another scientist involved in the “discovery” of ESR was a Swedish internist, Alf Vilhelm Albertsson Westergren (1891-1968). Based on observations of the sedimentation of blood obtained from patients with pulmonary tuberculosis, he presented a similar description of the phenomenon of ESR55 as those given by Biernacki, Hirszfeld, and Fåhraeus. Westergren applied a blood-sampling method to the ESR test using sodium citrate as an anticoagulant. This method of carrying out the ESR test was later recommended by the International Council for Standardization in Hematology (ICSH).56, 57, 58 According to these recommendations, Westergren's ESR test should be performed by filling a 300-mm long pipette graduated to 200 mm with 3.8% trisodium citrate dihydrate, and blood taken from a patient (mixture ratio 1:5). Reading is made in millimeters after 60 minutes.

Westergren also defined standards for the ESR test. What is more, in 1965 he was on the expert panel on the ESR test established by the Third General Assembly of the International Committee for Standardization in Hematology.56 Hirszfeld and Fåhraeus, after hearing about the earlier publications of Biernacki, acknowledged his precedence to the discovery of the ESR. Westergren, however, in the review of the work on the ESR, did not include Biernacki's contributions.29 Hirszfeld believed that Fåhraeus's method was incomplete because he did not include anemia, which influenced the speed of ESR.52 Neither Biernacki's publications nor Hirszfeld's reports concerning ESR were mentioned in the recommendations of ICSH. These recommendations, however, do include both Fåhraeus's and Westergren's publications from 1921.56

Conclusions

This summary of the history of the discovery of the ESR is an example of the existing difficulties in the exchange of medical ideas, not only before the era of Medline and PubMed, but also at a time when medical publications were not yet dominated by the English language. Biernacki's achievements, both in the field of experimental medicine and in clinical studies, were quoted and commented on in German language medical literature,48, 59 especially until 1911. In connection with this, it should be emphasized that Biernacki's discovery is not an isolated historical fact, but a fact influencing further development of clinical diagnostics that uses the phenomenon of ESR.

Biernacki's papers17, 18 stimulated, to a very significant extent, the scientific discussion about ESR in the medical literature.48, 59 There are many causes of the lack of recognition in the medical literature of Biernacki's input into the discovery of ESR, one of which is that after Biernacki's premature death in 1911 until 1917 no mention of ESR was made in medical journals. Unfortunately, the state of “supplanting” Biernacki's achievements from the scientific awareness of the English language literature was not changed, even by Fåhraeus's opinion contained in his work on the ESR in 1921. There he states that “Biernacki has the merit of being the first to have sought to call attention to a practical clinical method of measuring in blood tests in which coagulation has been prevented, the sinking rapidity of the corpuscules.”54

On the 100th anniversary of Biernacki's death, it is worthwhile to remember his achievements as an internist, scientist-experimenter, and philosopher of medicine.

Edmund Biernacki (1866-1911): Discoverer of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate. On the 100th anniversary of his death - ScienceDirect

Edmund Biernacki (1866-1911): Discoverer of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate. On the 100th anniversary of his death

Author links open overlay panelAndrzejGrzybowskiMD, PhDabJarosławSakMD, PhDc

Redirecting

Abstract

In contemporary medicine, the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is used to assess severity in patients with such diseases as erysipelas, psoriasis, eosinophilic fasciitis, dermatomyositis, and Behçet's disease. We remember the scientific achievements of a Polish physician, the discoverer of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR), Edmund Faustyn Biernacki (1866-1911), on the 100th anniversary of his death. The practical application of ESR in clinical diagnostics in 1897 by Biernacki was little known for many years, because it was often neglected owing to the work of Robert Fåhraeus and Alf Westergren from 1921. In addition, it is also frequently omitted that before Westergren's and Fåhraeus's reports were published, ESR was also noticed by Ludwig Hirschfeld in 1917.

Introduction

The erythrocyte sedimentation rate (ESR) is used to assess the acute phase response of many inflammatory diseases. Contemporary dermatology uses the ESR test for assessing disease severity in patients with erysipelas,1, 2, 3, 4 psoriasis,5, 6, 7 eosinophilic fasciitis,8 dermatomyositis,9 and Behçet's disease.10, 11, 12 An elevated ESR is used as a key diagnostic criterion for polymyalgia rheumatica13 and an independent predictor of giant cell arteritis.14

This year, 2011, marks the 100th anniversary of the death of Edmund Faustyn Biernacki (1866-1911), a Polish physician (Figure 1), who discovered the phenomenon of ESR.

Fig. 1

Biernacki was one of the representatives of the Polish school of philosophy of medicine15, 16 and the first scientist to use ESR17, 18 in medical diagnostics. Unfortunately, these historical facts are frequently omitted in the English language literature. It was only in the last decade of the 20th19century and the first decade of the 21st20, 21, 22, 23, 24 century that Biernacki's name has appeared. This appearance was connected to the presentation of the Polish school of philosophy of medicine and the discussion on the history of the discovery of ESR. Before this, Polish authors occasionally appealed to acknowledge Biernacki's input into the discovery of ESR.25, 26, 27, 28, 29, 30 This probably contributed to the gradual “rehabilitation” of Biernacki's contribution to this discovery; however, incomplete information concerning the discovery of ESR, which omits Biernacki's input,31 still appears even in the most recent scientific reports.32, 33 Thus, on the 100-year anniversary of Biernacki's death, it is worthwhile to briefly introduce his life and major scientific accomplishments, especially compared with the short history of ESR.

Edmund Biernacki as a physician and philosopher of medicine

The life and professional activities of Edmund Faustyn Biernacki (1866-1911) (Figure 1) coincided with the period of Partitions of Poland. In the 19th century and almost the first 2 decades of the 20th century, the Polish people had no political autonomy while remaining under the Russian, German, and Austro-Hungarian occupation. Biernacki was born in the Russian partition on December 19, 1866, in the city of Opoczno. At the age of 18, he enrolled at the Medical Faculty of the Imperial University of Warsaw. He published his first scientific papers during his medical studies, and for one of them34he received a Gold Medal in a competition announced by the Faculty of Medicine.

After graduating in 1889, Biernacki worked as an assistant in the Therapeutic Department of the Imperial University of Warsaw. There, he published many papers in the field of gastroenterology, neurology, and metabolic disorders. In the following year, he received a scholarship from the Joseph Mianowski Fund35 to conduct research in foreign research centers. First, as an assistant, he held internships in the clinics of Wilhelm Heinrich Erb (1840-1921) and Johann Hoffmann (1857-1919) in Heidelberg, and Jean-Martin Charcot (1825-1893) in Paris.

As an independent researcher, he worked in Heidelberg, Paris, and Giessen. In Paris, under the tutelage of Georges Hayem (1841-1933), he devised methods of examining the gastric contents, and while staying in Giessen at Franz Riegel's (1843-1904) clinic, he examined the importance of saliva and oral digestive physiology in the pathophysiology of digestive processes occurring in the stomach.22, 27, 28 In subsequent years of his career, as the head of the Diagnostic Department of the Imperial University of Warsaw, he devoted much effort to research in the fields of neurology, cardiology, infectious diseases, and hematology. Studies in the field of hematology, which led him to the discovery of ESR, were conducted between 1893 and 1897.

The increasing russification of the Imperial University of Warsaw, including the university clinic, was probably the main factor that caused Biernacki to change his workplace.27 In July 1897, he became department head at the Wola Hospital in Warsaw, and during this period, his fascination with methodology of medical science and philosophy of medicine began. At the turn of the century, he published 3 books concerning these issues,36, 37, 38which presented a meta-analysis of the relationships between diagnostic and therapeutic possibilities of contemporary European medicine.

The fourth book, on the theory of health and illness,39 was published after his transfer to Lviv, which remained in the Austro-Hungarian annexation. This transfer was caused by economic reasons. Because Biernacki was held in high esteem by the Lviv medical environment, in December 1902, the Medical Faculty of the University of Lviv, in recognition of his work, abandoned the procedural nostrification of his diploma. It is essential to mention that during the Partition of Poland, physicians who changed their place of work by leaving for a different partition (occupation zone) were obligated to undergo such nostrification procedure.

In 1908, at the University of Lviv, Biernacki received a title of associate professor at the Department of General and Experimental Pathology. From Lviv, he often traveled to Carlsbad, where he ran a medical practice in a local spa. He died suddenly in Lviv on December 29, 1911, at the age of 45. Unfortunately, he did not live to see the Polish nation gain independence in 1918.

Despite his premature death, his scientific achievements were quite impressive, as he published 98 scientific papers, including experimental and theoretical ones,22, 28 almost all of which were published in both Polish and German. Biernacki's contributions appeared in 21 scientific German language journals. Apart from explaining the nature of ESR, he was also the discoverer of one of the clinical manifestations of tabes dorsalis. In neurology, this symptom, which manifests itself by the analgesia of the ulnar nerve, is called the Biernacki sign.28 At the turn of the 19th and 20th centuries, Biernacki was known in the world literature as an outstanding expert on metabolic disorders. In Norden's textbook, which concerned this issue, apart from many quotes, Biernacki was described as “Der recht kritische Biernacki” (“rightly critical Biernacki”).40

The discovery of ESR

Beginning in ancient times, bloodletting with which the sick were treated, made it possible to make empirical observations on the red blood clot as being covered with a layer of whitish fluid called “crusta phlogistica” or “crusta inflammatoria.”41 In modern times, a Scottish surgeon, John Hunter (1728-1793),21 and a German physician, Hermann Nasse (1807-1892), are believed to be the discoverers of the ESR. In this context, it is also worth mentioning the London physician, William Hewson (1739-1774), considered the “father of hematology,”42 as the first person who noticed that the separation of defibrinated blood occurs more slowly than in the case of undefibrinated blood43; however, the first person to explain this phenomenon by means of an experiment and to use it in clinical diagnostics was Edmund Faustyn Biernacki.17, 18, 22, 24, 25,27, 28, 29, 30,44 The explanation of ESR that was provided by Biernacki was based on proving a close relationship between the speed of sedimentation of red blood cells and the level of fibrinogen.17, 18 Simultaneously, in 1894, Biernacki published his first reports about ESR in the Proceedings of the Warsaw Medical Society,45Wiener Medicinische Wochenschrift,46 and Zeitschrift für physiologische Chemie47; however, he did not include the evaluation of its usefulness in medical diagnostics.

In 1897, Biernacki announced the diagnostic value of ESR together with a pathophysiological explanation of this phenomenon in 2 contributions: one written in Polish in Gazeta Lekarska17 (Figure 2) and the second in German in the Deutsche Medicinische Wochenschrift18 (Fig. 3, Fig. 4). Shortly before the publication of his works describing ESR, during a meeting of the Warsaw Medical Society on June 22, 1897, Biernacki presented the 5 most important conclusions from his observations.22, 28 Those conclusions were as follows: the blood sedimentation rate and volume of residue produced is different in different individuals; blood with small amounts of red blood cells sediments faster; blood sedimentation rate depends on the level of fibrinogen in the blood plasma; during the course of febrile diseases (rheumatic fever included) with large amounts of plasma fibrinogen, the ESR is increased; in defibrinated blood, the sedimentation process is slower.27 Biernacki's findings clearly proved the clinical importance of the discovery of ESR. They indicated the sedimentary features of the plasma fibrinogen, which occurs in increased amounts in febrile disease.

Fig. 2

Fig. 3

Fig. 4

The application of ESR by Biernacki in clinical diagnostics was described in detail in 1902 in a textbook on blood pathology written by Gravitz.48 In 1906, Biernacki modified his method by using a capillary pipette of his own design, called a “microsedimentator,”22, 49 instead of the original glass cylinder (Figure 4). This technique allowed the measurement of ESR after sampling of the capillary blood from the tip of the finger. The reading of the results was possible after 60 minutes. As an anticoagulant, Biernacki used powdered sodium oxalate.

It is immensely interesting that 20 years after Biernacki's publication concerning ESR, 3 independent scientists made similar “discoveries.” Those scientists were Ludwik Hirszfeld (1884-1954), Robert Sanno Fåhraeus (1888-1968), and Alf Vilhelm Albertsson Westergren (1891-1968). First in 1917, 6 years after Biernacki's death, a Polish physician of Jewish origins, who later became famous for research on blood groups and the Rh factor, Ludwik Hirszfeld50, 51 presented a report on ESR. In blood taken from patients diagnosed with malaria, Hirszfeld observed the phenomenon of ESR.52 These observations were made during his stay in Serbia during an outbreak of malaria in 1917.

A year after Hirszfeld's report, a Swedish haematologist, Robert Sanno Fåhraeus, also announced his “discovery.” He analyzed the time differences of erythrocyte sedimentation occurring in 2 groups of women: pregnant and nonpregnant. He presented the results of his work in 1918,53 and 3 years later, he extensively discussed it in the journal Acta Medica Scandinavica.54Fåhraeus saw using ESR as a possible pregnancy test.

Another scientist involved in the “discovery” of ESR was a Swedish internist, Alf Vilhelm Albertsson Westergren (1891-1968). Based on observations of the sedimentation of blood obtained from patients with pulmonary tuberculosis, he presented a similar description of the phenomenon of ESR55 as those given by Biernacki, Hirszfeld, and Fåhraeus. Westergren applied a blood-sampling method to the ESR test using sodium citrate as an anticoagulant. This method of carrying out the ESR test was later recommended by the International Council for Standardization in Hematology (ICSH).56, 57, 58 According to these recommendations, Westergren's ESR test should be performed by filling a 300-mm long pipette graduated to 200 mm with 3.8% trisodium citrate dihydrate, and blood taken from a patient (mixture ratio 1:5). Reading is made in millimeters after 60 minutes.

Westergren also defined standards for the ESR test. What is more, in 1965 he was on the expert panel on the ESR test established by the Third General Assembly of the International Committee for Standardization in Hematology.56 Hirszfeld and Fåhraeus, after hearing about the earlier publications of Biernacki, acknowledged his precedence to the discovery of the ESR. Westergren, however, in the review of the work on the ESR, did not include Biernacki's contributions.29 Hirszfeld believed that Fåhraeus's method was incomplete because he did not include anemia, which influenced the speed of ESR.52 Neither Biernacki's publications nor Hirszfeld's reports concerning ESR were mentioned in the recommendations of ICSH. These recommendations, however, do include both Fåhraeus's and Westergren's publications from 1921.56

Conclusions

This summary of the history of the discovery of the ESR is an example of the existing difficulties in the exchange of medical ideas, not only before the era of Medline and PubMed, but also at a time when medical publications were not yet dominated by the English language. Biernacki's achievements, both in the field of experimental medicine and in clinical studies, were quoted and commented on in German language medical literature,48, 59 especially until 1911. In connection with this, it should be emphasized that Biernacki's discovery is not an isolated historical fact, but a fact influencing further development of clinical diagnostics that uses the phenomenon of ESR.

Biernacki's papers17, 18 stimulated, to a very significant extent, the scientific discussion about ESR in the medical literature.48, 59 There are many causes of the lack of recognition in the medical literature of Biernacki's input into the discovery of ESR, one of which is that after Biernacki's premature death in 1911 until 1917 no mention of ESR was made in medical journals. Unfortunately, the state of “supplanting” Biernacki's achievements from the scientific awareness of the English language literature was not changed, even by Fåhraeus's opinion contained in his work on the ESR in 1921. There he states that “Biernacki has the merit of being the first to have sought to call attention to a practical clinical method of measuring in blood tests in which coagulation has been prevented, the sinking rapidity of the corpuscules.”54

On the 100th anniversary of Biernacki's death, it is worthwhile to remember his achievements as an internist, scientist-experimenter, and philosopher of medicine.

Edmund Biernacki (1866-1911): Discoverer of the erythrocyte sedimentation rate. On the 100th anniversary of his death - ScienceDirect