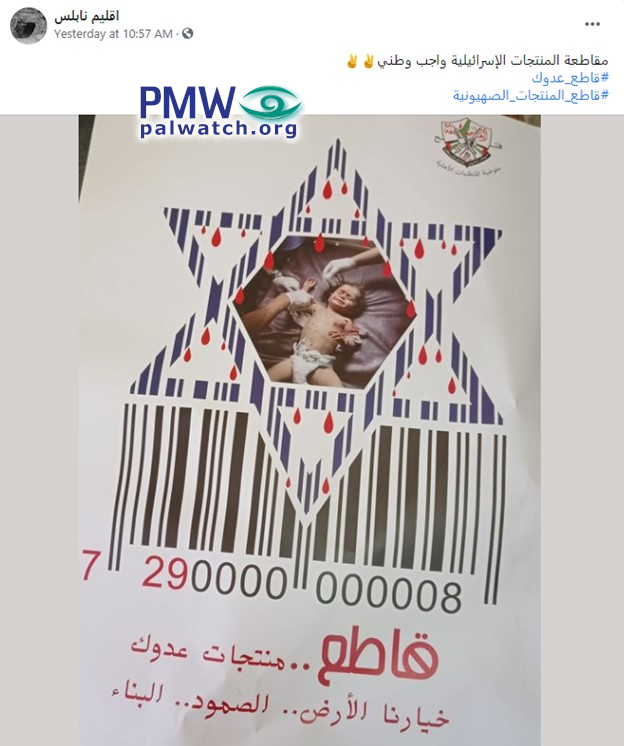

Those, like the U.S., who are looking to bolster Abbas are likely fighting an uphill battle. Throughout history, Palestinian leaders have encouraged “intifadas” (violent uprisings) resulting in lost lives, Jewish and Arab alike — and also in the replacement of one Palestinian political elite with another.

The first “intifada” did not begin in 1987, as commonly supposed. Rather, it began half a century earlier.

At the time, Palestinian Arab politics was dominated by Amin al-Husseini, who had been appointed by the ruling British as the grand mufti of Jerusalem. Husseini had incited anti-Jewish violence in

1920,

1921, and

1929. But by the 1930s he came under increasing

criticism from firebrands such as Sheikh Izz ad-Din al-Qassam, who argued that he was not being militant enough in combating Zionism.

When Qassam and some supporters murdered a British policeman and were subsequently killed in November 1935, his well-attended funeral sparked what has commonly been called the “Arab Revolt,” but which,

in truth, was the first intifada. Husseini

hoped to capitalize on the growing violence. Armed and equipped by the authoritarian anti-Semitic powers of the day — fascist Italy and Nazi Germany — Husseini’s forces murdered Jews and British officials. Husseini also used the occasion to assassinate and eliminate members of the Nashashibi clan, his chief rivals for power.

By the time the intifada was crushed in 1939, Husseini had been banished from British-ruled Mandatory Palestine. Many of his followers and supporters had been killed by the British, but he himself was now the undisputed master of Palestinian Arab politics. Despite his World War II-era collaboration with the Nazis, Husseini remained the dominant force among Palestinians for

at least another decade, only declining in influence when his forces failed to destroy the fledgling Jewish state in Israel’s 1948 War of Independence.

Fifty years later, in December 1987, anti-Jewish violence again erupted, perpetrated by young Palestinians, many of whom were critical of the old guard of Yasser Arafat’s Fatah movement. Younger Fatah members felt that Arafat and other Fatah founders were old, out of touch, and corrupt. Like Husseini before him, Arafat tried to capitalize on the fire that others had lit, attempting to use the intifada to regain relevance. Arafat would manage to maintain his dominance thanks in no small part to the U.S.-backed

Oslo Accords, which allowed him to lead the newly created Palestinian Authority. But he would spend the next two decades alternately battling and cooperating with younger rivals and groups such as Hamas.

(full article online)

For Palestinian leaders who choose to promote them, intifadas are often self-defeating.

www.nationalreview.com

www.al-monitor.com