In Detroit -

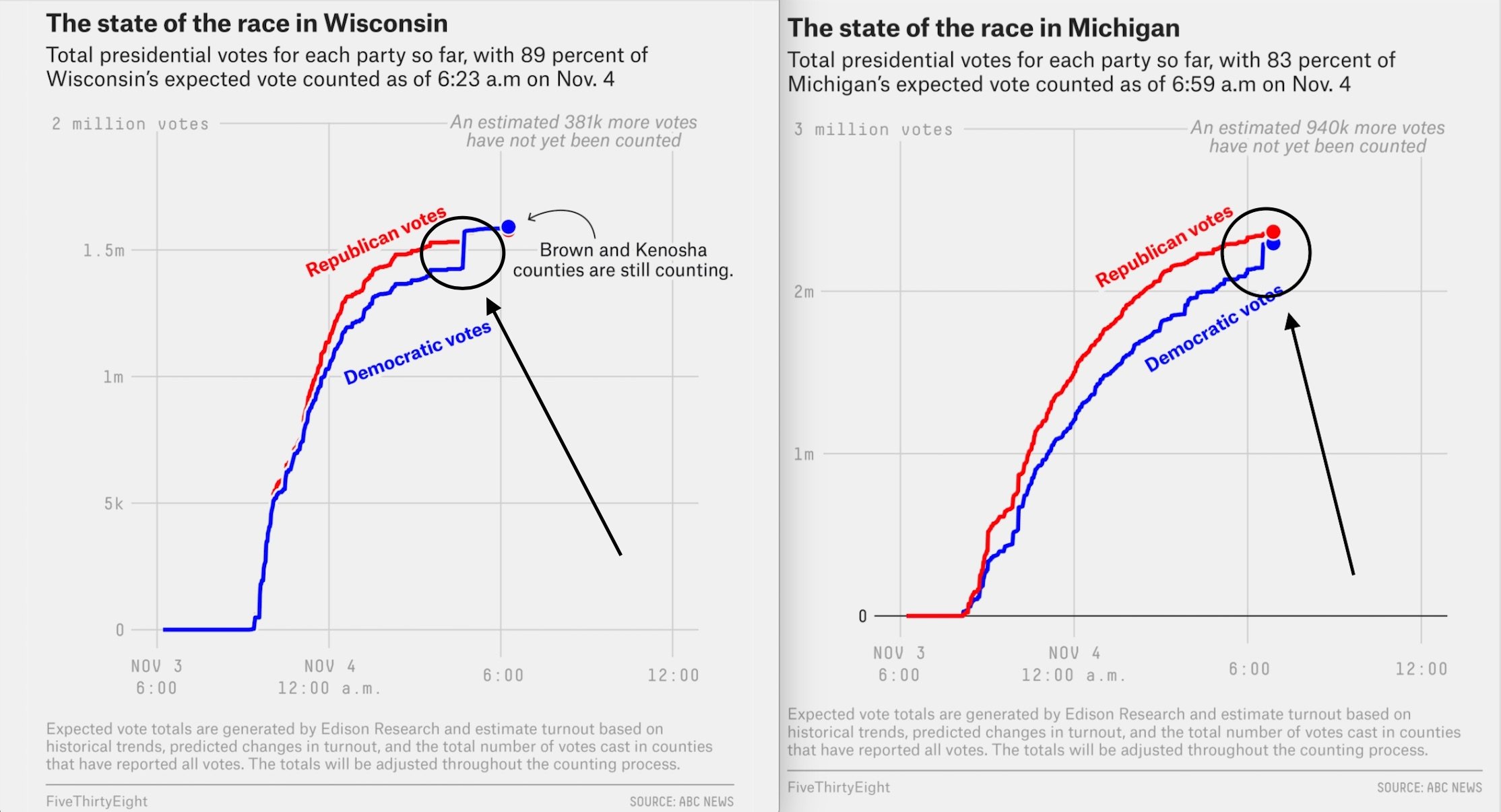

By five o’clock on Wednesday morning, it was apparent Trump’s lead would not hold.

Deprogramming Confederates Part 4

It was clear Trump was running far more competitively than they’d anticipated; he was on track to win Florida, Ohio and North Carolina, three states that tally their ballots quickly, meaning the spotlight would abruptly shift to the critical, slow-counting battlegrounds of Michigan, Wisconsin and Pennsylvania.

Everyone here knew this had been a possibility, but it wasn’t until midnight that the urgency of the situation crashed o over Republicans. Trump had built a lead of nearly 300,000 votes on the strength of same-day ballots that were disproportionately favorable to him. Now, with the eyes of the nation—and of the president—fixed on their state, Michigan Republicans scrambled to protect that lead. Laura Cox, chair of the state party, began dialing prominent lawmakers, attorneys and activists, urging them to get down to the TCF Center, the main hub of absentee vote counting in Detroit. She was met with some confusion; there were already plenty of Republicans there, as scheduled, working their shifts as poll challengers. It didn’t matter, Cox told them. It was time to flood the zone.

“This was all so predictable,” said Josh Venable, who ran Election Day operations for the Michigan GOP during five different cycles. “Detroit has been the boogeyman for Republicans since before I was born. It’s always been the white suburbs vs. Detroit, the white west side of the state vs. Detroit. There’s always this rallying cry from Republicans—‘We win everywhere else, but lose Wayne County’—that creates paranoia. I still remember hearing, back on my first campaign in 2002, that Wayne County always releases its votes last so that Detroit can see how many votes Democrats need to win the state. That’s what a lot of Republicans here believe.”

As things picked up at the TCF Center, with more and more white Republicans filing into the complex to supervise the activity of mostly Black poll workers, Chris Thomas noticed a shift in the environment. Having been brought out of retirement to help supervise the counting in Detroit—a decision met with cheers from Republicans and Democrats alike—Thomas had been “thrilled” with the professionalism he’d witnessed during Monday’s pre-processing session and Tuesday’s vote tabulating. Now, in the early morning hours of Wednesday, things were going sideways. Groups of Republican poll challengers were clustering around individual counting tables in violation of the rules. People were raising objections—such as to the transferring of military absentees onto ballots that could be read by machines, a standard practice—that betrayed a lack of preparation.

“Reading these affidavits afterward from these Republican poll challengers, I was just amazed at how misunderstood the election process was to them,” Thomas chuckled. “The things they said were going on—it’s like ‘Yeah, that’s exactly what was going on. That’s what’s supposed to happen.’” (The Trump team’s much celebrated lawsuit against Detroit was recently withdrawn after being pummeled in local courtrooms; his campaign has to date won one case and lost 35.)

At one point, around 3:30 in the morning, Thomas supervised the receiving of Detroit’s final large batch of absentee ballots. They arrived in a passenger van. Thomas confirmed the numbers he’d verified over the phone: 45 trays, each tray holding roughly 300 ballots, for a total of between 13,000 and 14,000 ballots. Not long after, Charlie Spies, an attorney for the U.S. Senate campaign of Republican John James, approached Thomas inside the TCF Center. He wanted to know about the 38,000 absentee ballots that had just materialized. Thomas told him there were not 38,000 ballots; that at most it might have been close to 15,000.

“I was told the number was 38,000,” Spies replied.

By five o’clock on Wednesday morning, it was apparent Trump’s lead would not hold.