Xenophon

Gone and forgotten

After the defeat of Spain's Invincible Armada in 1588, her power began to decline. She had lost so many naval vessels that she could no longer adequately protect the merchant ships that plied back and forth between Spanish home ports and the Caribbean. Neither was she able to prevent the colonization of some of her West Indian islands by men of other nations. In 1623 St. Kitts was settled by the English; their claim was challenged in 1625 when France also claimed the island. In 1628 the dispute was settled by dividing rule of the island between the two nations. The joint governors of the island were Pierre Belain d'Esnambuc, a former French pirate, and Sir Thomas Warner, who was the first colonial authority to be appointed by the British Crown for official duty in the West Indies.

The Dutch (who were in the midst of winning their independence from Spain) were on the prowl also. One of their most extraordinary exploits was accomplished by Piet Heyn, admiral of a fleet of men-of-war sent to prey on the Spaniards by the Dutch West India Company. In September, 1628, Heyn lay off Cape San Antonio, on the northern coast of Cuba, waiting for the great Spanish plate fleet to set sail. His squadron consisted of thirty-one vessels mounting seven hundred cannon, manned by almost three thousand hardy Dutch fighting men. Soon after the heavily laden galleons put to sea, Heyn and his ships swooped down upon them. The Spaniards tried -to make a running fight of it, but the entire Spanish treasure fleet was captured. The booty included cargoes of gold, silver, pearls, logwood, and indigo. The total value was nearly five million dollars. The Dutch West India Company declared a fifty per cent dividend to its stockholders. But the Spanish admiral responsible for the loss of the plate fleet was declared a liability by the Crown of Spain and was beheaded soon after he reached his country.

At about this same time, adventurers began coming to other West Indian islands from all parts of Europe, greedy for quickly won riches. In small groups they began drifting to the western end of the great island of Hispaniola (divided today between Haiti and the Dominican Republic). Some were deserters from ships, runaway servants, criminals, and a few were young men of good family, thirsting for adventure. They camped on the rolling savannas of Hispaniola and hunted wild cattle and hogs, which were the descendants of those that originally had been brought over by Spanish settlers in the early 1500's. The hunters dried and salted the meat over grills made of green wood called boucans. A French hunter called himself a boucanier. The English equivalent was buccaneer. They wore peaked caps and dressed in rough shirts and pantaloons stained with the blood of the cattle they butchered. They were hairy, dirty rascals who were armed with six-foot French firelocks and belts full of knives. They sold their dried meat to passing ships, plantation owners, and people of the small coastal settlements. Ships' captains were eager to buy the dried meat, for it would keep without spoiling on long voyages.

When the hunting season was over, the buccaneers would sail to the neighboring island of Tortuga. Tortuga is the Spanish word for turtle; the island was so called because it is shaped like a sea turtle. On Tortuga the buccaneers would buy provisions, powder, and bullets, and spend their time drinking and carousing.

Tortuga was originally settled by Spanish planters who tried to cultivate tobacco and sugar, without much success. Strategically located close to the northwestern tip of Hispaniola, Tortuga commanded Windward Passage between Hispaniola and Cuba, through which the vessels of Spain often sailed on their homeward voyages. It soon became the headquarters of rovers, freebooters, and pirates.

When the hunting was poor on Hispaniola, a group of buccaneers would put to sea in a small boat, searching for a larger vessel to capture. Their favorite time of attack was at dusk or just before dawn. For it was at these hours of the day that ships were most likely to be trying to pass Tortuga. All day long steady trade winds blew in from the Atlantic, making it almost impossible for sailing ships to beat their way out of the Caribbean and through straits such as the Windward Passage. But from dusk until dawn, when the direction of the winds was usually reversed and blew out toward the Atlantic, vessels had a much better chance to slip through the pirate-infested islands and gain the ocean.

The pirates relied heavily on surprise, followed by fierce hand-to-hand combat. Once in command of the captured vessel, they would continue their voyage of plunder.

One of the dread pirates of Tortuga was Pierre Ie Grand, a Frenchman who in 1665 performed one of the boldest feats in the history of buccaneering. One day at dusk, having been at sea in command of a small open boat for a long time without capturing anything, he sighted a great Spanish galleon that had become separated from the rest of the plate fleet. Le Grand and his men determined to try to capture her, for they were half-starved and desperate. What happened next is told by a contemporary, Alexander Exquemelin (sometimes called John Esquemeling), a young French doctor who sailed with the buccaneers and wrote a book about his adventures called The Buccaneers of America: "It was in the dusk of the evening, or soon after, when this great action was performed. But, before it was begun, they gave orders unto the surgeon of the boat to bore a hole in the side thereof, to the intent that, their own vessel sinking under them, they might be compelled to attack more vigorously." This was performed accordingly; and without any other arms than a pistol in the belt and a sword in one hand, they hurriedly "climbed up the sides of the ship, and ran altogether into the great cabin, where they found the Captain, with several of Ins companions, playing at cards. Here they set a pistol to his breast, commanding him to deliver up the ship unto their obedience.

"The Spaniards, seeing the Pirates aboard their ship, without scarce seeing them at sea, cried out, 'Jesus bless us! Are these devils, or what are they?' In the meanwhile, some of them took possession of the gun room, and seized the arms and military affairs they found there, killing as many of the ship as made any opposition. By which means the Spaniards were compelled to surrender."

No sooner had the news of this remarkable capture reached Tortuga and Hispaniola, than most of the hunters made up their minds to follow Le Grand's example. "Toward the coast of Campeche, and . . . toward that of New Spain," they plundered many Spanish ships, not only of gold and silver but also of valuable cargoes of cocoa, tobacco, sugar, rum, and indigo.

"Being arrived at Tortuga with these prizes, and the whole people of the island admiring their progresses, especially that within the space of two years the riches of the country were much increased, the number of Pirates did augment so fast . . . there were to be numbered in that small island and port above twenty ships of this sort of people."

The buccaneers were fiercely independent and very democratic in their dealings with each other. Beginning about 1640, they formed a sort of confraternity, calling themselves the Brothers of the Coast. To become a member, a buccaneer had to vow to follow a strict code called the Custom of the Coast. This set forth specific rules for the election of the ship's captain and officers and the division of booty. Invariably the man chosen to be captain was one who had distinguished himself in battle and was a natural leader. Provision was also made for compensating members of the crew who were wounded, as well as punishing those who disobeyed the code. For example, if a Brother was found stealing from another, he had his ears and nose cut off. If he committed a second offense, he was marooned (or abandoned) on a desert island with only a musket, ammunition, and a bottle of water.

Rewards were given for sighting a prize, capturing an enemy's flag, or for especially good marksmanship. Every man aboard ship, from the captain to the cabin boy, was allotted shares in the spoils according to articles signed at the beginning of the voyage.

Exquemelin describes the division of the booty thus; "The Captain ... is allotted five or six portions to what the ordinary seamen have; the Master's Mate only two; and other Officers proportionable to their employment. After whom they draw equal parts from the highest even to the lowest mariner, the boys [often kidnapped by buccaneers from European ports] not being omitted. For even these draw half a share, by reason that, when they happen to take a better vessel than their own, it is the duty of the boys to set fire unto the ship . . . then retire unto the prize which they have taken."

The Brothers of the Coast also had their own form of accident insurance. The loss of an eye in battle was compensated by a hundred pieces of eight or the gift of a slave. If a man lost his right hand or arm he received six hundred pieces of eight or six slaves. Other injuries were paid for in proportion to their seriousness.

The largest vessels used by the buccaneers were armed frigates mounting from fifty to ninety guns. When approaching the enemy, the crew of the smaller ships lay flat on deck to avoid enemy fire, usually grapeshot. When close, they threw grappling irons aboard the other ship and drew themselves over the bulwarks, pistols cocked, cutlasses and axes in their belts and knives in their teeth. They threw themselves against their Spanish foes with wild cries, shooting them at close range or cutting them down with their edged weapons. Once masters of the prize, they often massacred the survivors or threw them overboard.

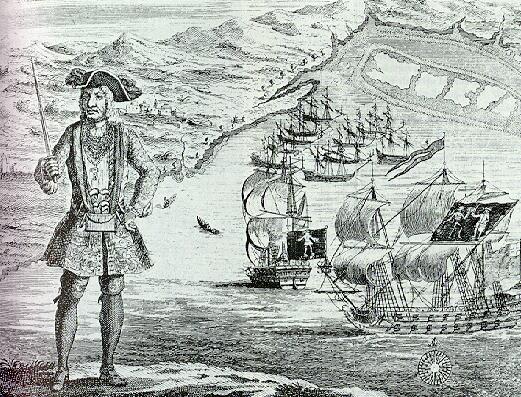

The seagoing buccaneers were a colorful and unruly lot of many nationalities: chiefly French, English, Dutch, Flemish, as well as some Greeks, Levantines, Portuguese, Negroes, and Indians. They wore any sort of clothing that suited their fancy, often fine silks and velvets captured from their wealthy Spanish victims. They delighted in jewelry and ornaments of all kinds, wearing gold chains, numerous rings and bracelets and armbands, and great earrings dangling from their weatherbeaten ears.

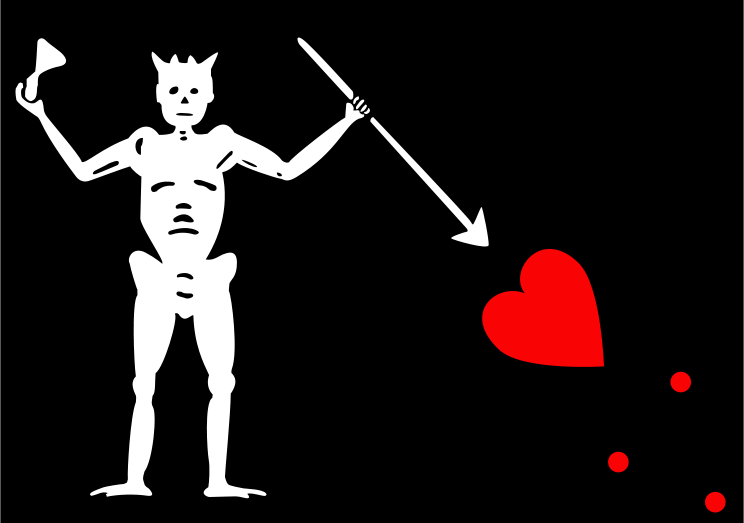

During the latter half of the sixteenth century, when Spain, England, Holland, and France were so often at war with each other, the buccaneer captains were often given letters of marque to capture enemy ships and their cargoes. In times of peace, as pirates, they attacked any vessel that came their way.

For nearly three hundred years their daring deeds made the buccaneers the terror of the Caribbean, and the stories of their bold adventures and tales of buried treasure would live on long after all of them were dead.

The Dutch (who were in the midst of winning their independence from Spain) were on the prowl also. One of their most extraordinary exploits was accomplished by Piet Heyn, admiral of a fleet of men-of-war sent to prey on the Spaniards by the Dutch West India Company. In September, 1628, Heyn lay off Cape San Antonio, on the northern coast of Cuba, waiting for the great Spanish plate fleet to set sail. His squadron consisted of thirty-one vessels mounting seven hundred cannon, manned by almost three thousand hardy Dutch fighting men. Soon after the heavily laden galleons put to sea, Heyn and his ships swooped down upon them. The Spaniards tried -to make a running fight of it, but the entire Spanish treasure fleet was captured. The booty included cargoes of gold, silver, pearls, logwood, and indigo. The total value was nearly five million dollars. The Dutch West India Company declared a fifty per cent dividend to its stockholders. But the Spanish admiral responsible for the loss of the plate fleet was declared a liability by the Crown of Spain and was beheaded soon after he reached his country.

At about this same time, adventurers began coming to other West Indian islands from all parts of Europe, greedy for quickly won riches. In small groups they began drifting to the western end of the great island of Hispaniola (divided today between Haiti and the Dominican Republic). Some were deserters from ships, runaway servants, criminals, and a few were young men of good family, thirsting for adventure. They camped on the rolling savannas of Hispaniola and hunted wild cattle and hogs, which were the descendants of those that originally had been brought over by Spanish settlers in the early 1500's. The hunters dried and salted the meat over grills made of green wood called boucans. A French hunter called himself a boucanier. The English equivalent was buccaneer. They wore peaked caps and dressed in rough shirts and pantaloons stained with the blood of the cattle they butchered. They were hairy, dirty rascals who were armed with six-foot French firelocks and belts full of knives. They sold their dried meat to passing ships, plantation owners, and people of the small coastal settlements. Ships' captains were eager to buy the dried meat, for it would keep without spoiling on long voyages.

When the hunting season was over, the buccaneers would sail to the neighboring island of Tortuga. Tortuga is the Spanish word for turtle; the island was so called because it is shaped like a sea turtle. On Tortuga the buccaneers would buy provisions, powder, and bullets, and spend their time drinking and carousing.

Tortuga was originally settled by Spanish planters who tried to cultivate tobacco and sugar, without much success. Strategically located close to the northwestern tip of Hispaniola, Tortuga commanded Windward Passage between Hispaniola and Cuba, through which the vessels of Spain often sailed on their homeward voyages. It soon became the headquarters of rovers, freebooters, and pirates.

When the hunting was poor on Hispaniola, a group of buccaneers would put to sea in a small boat, searching for a larger vessel to capture. Their favorite time of attack was at dusk or just before dawn. For it was at these hours of the day that ships were most likely to be trying to pass Tortuga. All day long steady trade winds blew in from the Atlantic, making it almost impossible for sailing ships to beat their way out of the Caribbean and through straits such as the Windward Passage. But from dusk until dawn, when the direction of the winds was usually reversed and blew out toward the Atlantic, vessels had a much better chance to slip through the pirate-infested islands and gain the ocean.

The pirates relied heavily on surprise, followed by fierce hand-to-hand combat. Once in command of the captured vessel, they would continue their voyage of plunder.

One of the dread pirates of Tortuga was Pierre Ie Grand, a Frenchman who in 1665 performed one of the boldest feats in the history of buccaneering. One day at dusk, having been at sea in command of a small open boat for a long time without capturing anything, he sighted a great Spanish galleon that had become separated from the rest of the plate fleet. Le Grand and his men determined to try to capture her, for they were half-starved and desperate. What happened next is told by a contemporary, Alexander Exquemelin (sometimes called John Esquemeling), a young French doctor who sailed with the buccaneers and wrote a book about his adventures called The Buccaneers of America: "It was in the dusk of the evening, or soon after, when this great action was performed. But, before it was begun, they gave orders unto the surgeon of the boat to bore a hole in the side thereof, to the intent that, their own vessel sinking under them, they might be compelled to attack more vigorously." This was performed accordingly; and without any other arms than a pistol in the belt and a sword in one hand, they hurriedly "climbed up the sides of the ship, and ran altogether into the great cabin, where they found the Captain, with several of Ins companions, playing at cards. Here they set a pistol to his breast, commanding him to deliver up the ship unto their obedience.

"The Spaniards, seeing the Pirates aboard their ship, without scarce seeing them at sea, cried out, 'Jesus bless us! Are these devils, or what are they?' In the meanwhile, some of them took possession of the gun room, and seized the arms and military affairs they found there, killing as many of the ship as made any opposition. By which means the Spaniards were compelled to surrender."

No sooner had the news of this remarkable capture reached Tortuga and Hispaniola, than most of the hunters made up their minds to follow Le Grand's example. "Toward the coast of Campeche, and . . . toward that of New Spain," they plundered many Spanish ships, not only of gold and silver but also of valuable cargoes of cocoa, tobacco, sugar, rum, and indigo.

"Being arrived at Tortuga with these prizes, and the whole people of the island admiring their progresses, especially that within the space of two years the riches of the country were much increased, the number of Pirates did augment so fast . . . there were to be numbered in that small island and port above twenty ships of this sort of people."

The buccaneers were fiercely independent and very democratic in their dealings with each other. Beginning about 1640, they formed a sort of confraternity, calling themselves the Brothers of the Coast. To become a member, a buccaneer had to vow to follow a strict code called the Custom of the Coast. This set forth specific rules for the election of the ship's captain and officers and the division of booty. Invariably the man chosen to be captain was one who had distinguished himself in battle and was a natural leader. Provision was also made for compensating members of the crew who were wounded, as well as punishing those who disobeyed the code. For example, if a Brother was found stealing from another, he had his ears and nose cut off. If he committed a second offense, he was marooned (or abandoned) on a desert island with only a musket, ammunition, and a bottle of water.

Rewards were given for sighting a prize, capturing an enemy's flag, or for especially good marksmanship. Every man aboard ship, from the captain to the cabin boy, was allotted shares in the spoils according to articles signed at the beginning of the voyage.

Exquemelin describes the division of the booty thus; "The Captain ... is allotted five or six portions to what the ordinary seamen have; the Master's Mate only two; and other Officers proportionable to their employment. After whom they draw equal parts from the highest even to the lowest mariner, the boys [often kidnapped by buccaneers from European ports] not being omitted. For even these draw half a share, by reason that, when they happen to take a better vessel than their own, it is the duty of the boys to set fire unto the ship . . . then retire unto the prize which they have taken."

The Brothers of the Coast also had their own form of accident insurance. The loss of an eye in battle was compensated by a hundred pieces of eight or the gift of a slave. If a man lost his right hand or arm he received six hundred pieces of eight or six slaves. Other injuries were paid for in proportion to their seriousness.

The largest vessels used by the buccaneers were armed frigates mounting from fifty to ninety guns. When approaching the enemy, the crew of the smaller ships lay flat on deck to avoid enemy fire, usually grapeshot. When close, they threw grappling irons aboard the other ship and drew themselves over the bulwarks, pistols cocked, cutlasses and axes in their belts and knives in their teeth. They threw themselves against their Spanish foes with wild cries, shooting them at close range or cutting them down with their edged weapons. Once masters of the prize, they often massacred the survivors or threw them overboard.

The seagoing buccaneers were a colorful and unruly lot of many nationalities: chiefly French, English, Dutch, Flemish, as well as some Greeks, Levantines, Portuguese, Negroes, and Indians. They wore any sort of clothing that suited their fancy, often fine silks and velvets captured from their wealthy Spanish victims. They delighted in jewelry and ornaments of all kinds, wearing gold chains, numerous rings and bracelets and armbands, and great earrings dangling from their weatherbeaten ears.

During the latter half of the sixteenth century, when Spain, England, Holland, and France were so often at war with each other, the buccaneer captains were often given letters of marque to capture enemy ships and their cargoes. In times of peace, as pirates, they attacked any vessel that came their way.

For nearly three hundred years their daring deeds made the buccaneers the terror of the Caribbean, and the stories of their bold adventures and tales of buried treasure would live on long after all of them were dead.