Mindful

Diamond Member

- Banned

- #1

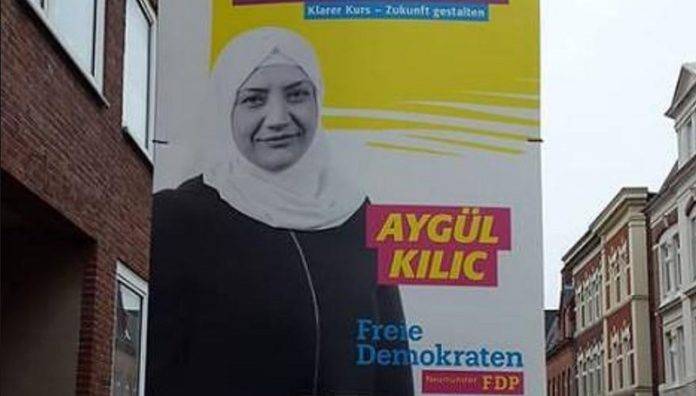

If Silicon Valley ever formed a political party, it might look a lot like the current iteration of Germany’s Free Democrats, or FDP. In the 2017 election cycle, the FDP offered a platform that reads like what Elon Musk and Mark Zuckerberg would come up with if they decided to disrupt Rand Paul. Its primary aspirations include creating a startup-friendly economy, digitizing Germany’s monolithic reams of bureaucratic paperwork (no small feat), and, yes, radically reduce income taxes, which currently top off at 45% for the highest earners.

The platform has propelled the party back from the dead. Having been kicked out of the Germany’s parliament, or Bundestag, in 2013, the FDP came roaring back with 10% of the vote in Sunday’s election.

The secret to Germany’s happiness and success: Its values are the opposite of Silicon Valley’s

The platform has propelled the party back from the dead. Having been kicked out of the Germany’s parliament, or Bundestag, in 2013, the FDP came roaring back with 10% of the vote in Sunday’s election.

The secret to Germany’s happiness and success: Its values are the opposite of Silicon Valley’s