I agree with most of these points and with your overall thrust. Just a few caveats:

Even when the mines were cleared from Haiphong Harbor, the port's capacity was still well below pre-mining levels due to the extensive damage caused by our Linebacker II bombing. As a result, Soviet aid received through the port in 1973 was only partially restored after the mines were gone.

Therefore, Chinese aid to North Vietnam actually eclipsed Soviet aid in 1973, even though China reduced its aid that year compared to 1972. In 1972, Chinese aid to North Vietnam was $2.23 billion, but in 1973 it was $1.55 billion. Soviet aid to North Vietnam in 1973 was $1.0 billion.

Haiphong Harbor's port capacity was finally restored in 1974. As a result, Soviet aid overtook Chinese aid in 1974, with Soviet aid rising to $1.7 billion that year, which amounted to a 70% increase over the previous year.

Soviet and Chinese aid to North Vietnam in 1973 ($2.55 billion) was 14% higher than our aid to South Vietnam in 1973 ($2.2 billion), and the disparity grew larger in 1974 and 1975, thanks to the back-stabbing anti-war majority in the U.S. Congress.

Congress slashed our aid to South Vietnam for 1974 and 1975, cutting aid from $2.2 billion in 1973 to $1.1 billion in 1974 and then to $700 million in 1975. When Congress passed the first cut in aid in 1973--for fiscal year 1974--the news naturally hurt morale in South Vietnam and boosted morale in Hanoi.

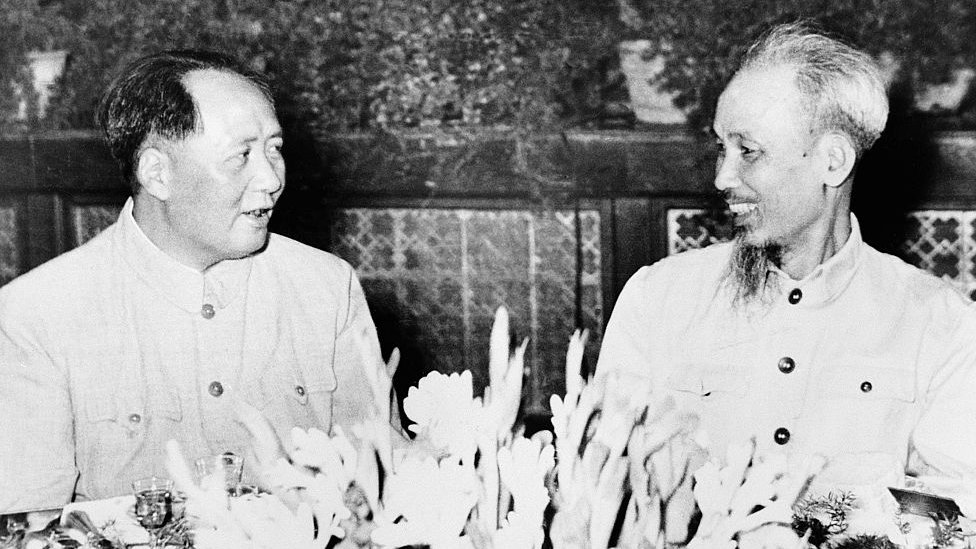

Another relevant fact is that the Soviets agreed to train leading North Vietnamese commanders in combined-arms tactics in Moscow in 1973, while we were forbidden from providing additional training to ARVN by the Paris Peace Accords. This crucial form of aid was never counted as part of the dollar value of Soviet aid. Dr. Michael Kort:

One of the key reasons the Easter Offensive failed is that General Giap did not understand h ow to coordinate what is known as combined arms operations: that is, the simultaneous use of different military arms–such as infantry, armor, and artillery– in an operation. This is essential in modern warfare given the great variety of available weapons, and after 1972 , as Veith notes, the PAVN “needed to become a modern army, and only the Soviets could train it in this type of warfare.” Therefore, in the fall of 1973, by which time the Paris Accords precluded the United States from providing any additional advising to the South Vietnamese, several leading North Vietnamese commanders went to the Soviet Union to train in this kind of warfare. Not coincidentally, this was only a few months after the North Vietnamese Politburo had voted to resume full-scale warfare to conquer the South. There is no way to measure the value of this aid in dollars; it does not appear on any ledger. What one can say given the conventional invasion Hanoi launched against South Vietnam in late 1974–an invasion spearheaded by armor, the “key to victory” according to Veith–is that this particular form of Soviet aid was invaluable. (The Vietnam War Reexamined, Cambridge University Press, 2018, p. 207)