Xenophon

Gone and forgotten

Yet another little tale to pass the time...

A race horse that changed into a cart horse

For 11 years the Dowager Lady Tichborne had waited for her son to return from the dead. Now the miracle had happened. In her hands she held a letter that seemed to justify the waiting and her faith.

The letter from Australia appeared to be from her long-lost son, Sir Roger Charles Doughty Tichborne, heir to the Tichborne estates in Hampshire, England, and descendant of a family dating back 200 years before the Norman Conquest. Though the handwriting was crude and the language smacked more of London's East End and them Australian bush than the drawing room, Lady Tichborne was pathetically eager to be convinced that the letter came from Sir Roger.

She had last seen him in March 1854, after he had resigned his commission as an officer of the Sixth Dragoons. A love affair with his cousin Katherine had broken up, and he decided to set off on a long tour of South America and Mexico to get her completely out of his mind.

By the following month he had reached Rio de Janeiro, which he left aboard the Bella of Liverpool. The ship was never seen again. As the months wore on, all hope of survivors disappeared. The letters Roger had asked to be directed to Kingston, Jamaica, remained uncollected. Eventually, Lloyd's of London wrote off the Bella as lost and settled insurance claims.

Roger's French-born mother, Henriette, refused to abandon hope and after the death of her husband, Sir James, clung even more to the conviction that her son was still alive.

She placed advertisements in several newspapers in South America and Australia, offering a reward for information. One of them was seen by Arthur Orton. The youngest of 12 children, he had been forced to leave his overcrowded home in London's East End and go to sea. In 1849 he deserted his ship in Valparaiso and some time later returned to England, using the name Joseph M. Orton. In 1852 he departed again, this time for Australia.

There he was alleged to have been a member of a horse-stealing gang. He next turned up as a cattle slaughterer in Wagga Wagga, and it was there in 1865 that he read Lady Tichborne's advertisement and began his long deception.

Orton was about to file a bankruptcy petition when he confessed to his lawyer that he had property in England. He also hinted that he had been shipwrecked. The lawyer, who had also seen the advertisement, was interested.

After Orton was seen carving the initials "RCT" on trees, posts, and even on his pipe, it was hardly surprising that his lawyer should ask him: "Are you Roger Tichborne?" The impostor allowed himself to be persuaded to write to Lady Tichborne about his "inheritance."

Deeply involved

Orton was by now far too deeply involved to back out as he had already raised about 20,000 pounds on the strength of his "expectations." In 1866 he and his family set sail for England.

Soon after he arrived, he traveled to Hampshire and quietly tried to familiarize himself with his "home" surroundings and at the same time enlist the support of the Tichborne locals.

But he met with little success. The village blacksmith dismissed Orton's suggestion that he was Sir Roger: "If you are, you've changed from a race horse to a cart horse!"

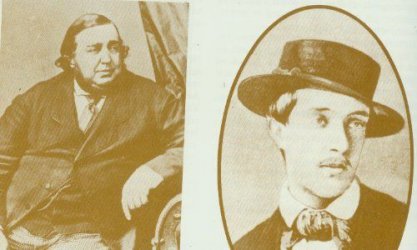

Sir Roger had weighed under 125 pounds, had a long, sallow face with straight dark hair, and had a tattoo on his left arm. Orton weighed 530 pounds and had a large, round face and wavy fair hair. He had no tattoo. In spite of this glaring disparity, Orton decided to meet Lady Tichborne. She was then living in Paris, and eventually, it was there, in Orton's hotel bedroom, that their meeting took place on a January afternoon. Orton said he was ill, and the room was kept darkened.

He spoke to her of his grandfather, whom the real Roger had never seen, wrongly said he had served in the ranks of the army, and referred to his school, Stonyhurst, as Winchester.

His blunders were glaring and, to anyone but a grief-stricken and self-deluding old woman, completely damning. But without hesitation she accepted him as her son. "He confuses everything as in a dream," she fondly observed.

The rest of the family, their friends, and servants refused to have anything to do with him, but this did not deter Orton. He began a legal action, claiming the Tichborne estates, worth between 20,000 and 25,000 pounds, from the trustees of the infant Sir Alfred Tichborne, posthumous son of Roger's younger brother. Before the case got to court, his case was drastically weakened by the sudden death of Lady Tichborne.

While he awaited the court hearing, Orton engaged as servants two men who had been in Roger's regiment. With their help he memorized many details of regimental life so well that 30 of the dead man's brother officers were willing to swear that he was Sir Roger despite his extraordinary change in appearance.

He produced more than 100 witnesses who testified that he was the real Sir Roger. None was really close to the family, but they made a powerful showing against the 17 who spoke against him.

Inevitably, it was his rough way of speaking that condemned him. "I would have won if only I could have kept my mouth shut," he said later.

The case went on for 102 days and cost the Tichborne family 90,000 pounds. After losing the action, Orton was charged with perjury. He was jailed for 14 years.

Loyal supporters

Amazingly, the discredited Orton still had supporters. Dr. Kenealy, the lawyer who defended him, tried to turn the case into a national issue, and his vehement defense led to his being disbarred for unprofessional conduct.

Orton completed 10 years of his i4-year sentence and, after his release, arranged a tour of public meetings in a vain attempt to regain sympathy. He also worked at a music hall and later in a saloon and a tobacconist's shop. With poverty facing him, he sold his "confession" to the newspaper People for 3,000 pounds. But he still died penniless.

Even in death, Orton was able to inspire the belief of one unknown person, for there is an inscription on his grave: "Sir Roger Charles Doughty Tichborne; born 5 January 1829; died 1 April 1898."

A race horse that changed into a cart horse

For 11 years the Dowager Lady Tichborne had waited for her son to return from the dead. Now the miracle had happened. In her hands she held a letter that seemed to justify the waiting and her faith.

The letter from Australia appeared to be from her long-lost son, Sir Roger Charles Doughty Tichborne, heir to the Tichborne estates in Hampshire, England, and descendant of a family dating back 200 years before the Norman Conquest. Though the handwriting was crude and the language smacked more of London's East End and them Australian bush than the drawing room, Lady Tichborne was pathetically eager to be convinced that the letter came from Sir Roger.

She had last seen him in March 1854, after he had resigned his commission as an officer of the Sixth Dragoons. A love affair with his cousin Katherine had broken up, and he decided to set off on a long tour of South America and Mexico to get her completely out of his mind.

By the following month he had reached Rio de Janeiro, which he left aboard the Bella of Liverpool. The ship was never seen again. As the months wore on, all hope of survivors disappeared. The letters Roger had asked to be directed to Kingston, Jamaica, remained uncollected. Eventually, Lloyd's of London wrote off the Bella as lost and settled insurance claims.

Roger's French-born mother, Henriette, refused to abandon hope and after the death of her husband, Sir James, clung even more to the conviction that her son was still alive.

She placed advertisements in several newspapers in South America and Australia, offering a reward for information. One of them was seen by Arthur Orton. The youngest of 12 children, he had been forced to leave his overcrowded home in London's East End and go to sea. In 1849 he deserted his ship in Valparaiso and some time later returned to England, using the name Joseph M. Orton. In 1852 he departed again, this time for Australia.

There he was alleged to have been a member of a horse-stealing gang. He next turned up as a cattle slaughterer in Wagga Wagga, and it was there in 1865 that he read Lady Tichborne's advertisement and began his long deception.

Orton was about to file a bankruptcy petition when he confessed to his lawyer that he had property in England. He also hinted that he had been shipwrecked. The lawyer, who had also seen the advertisement, was interested.

After Orton was seen carving the initials "RCT" on trees, posts, and even on his pipe, it was hardly surprising that his lawyer should ask him: "Are you Roger Tichborne?" The impostor allowed himself to be persuaded to write to Lady Tichborne about his "inheritance."

Deeply involved

Orton was by now far too deeply involved to back out as he had already raised about 20,000 pounds on the strength of his "expectations." In 1866 he and his family set sail for England.

Soon after he arrived, he traveled to Hampshire and quietly tried to familiarize himself with his "home" surroundings and at the same time enlist the support of the Tichborne locals.

But he met with little success. The village blacksmith dismissed Orton's suggestion that he was Sir Roger: "If you are, you've changed from a race horse to a cart horse!"

Sir Roger had weighed under 125 pounds, had a long, sallow face with straight dark hair, and had a tattoo on his left arm. Orton weighed 530 pounds and had a large, round face and wavy fair hair. He had no tattoo. In spite of this glaring disparity, Orton decided to meet Lady Tichborne. She was then living in Paris, and eventually, it was there, in Orton's hotel bedroom, that their meeting took place on a January afternoon. Orton said he was ill, and the room was kept darkened.

He spoke to her of his grandfather, whom the real Roger had never seen, wrongly said he had served in the ranks of the army, and referred to his school, Stonyhurst, as Winchester.

His blunders were glaring and, to anyone but a grief-stricken and self-deluding old woman, completely damning. But without hesitation she accepted him as her son. "He confuses everything as in a dream," she fondly observed.

The rest of the family, their friends, and servants refused to have anything to do with him, but this did not deter Orton. He began a legal action, claiming the Tichborne estates, worth between 20,000 and 25,000 pounds, from the trustees of the infant Sir Alfred Tichborne, posthumous son of Roger's younger brother. Before the case got to court, his case was drastically weakened by the sudden death of Lady Tichborne.

While he awaited the court hearing, Orton engaged as servants two men who had been in Roger's regiment. With their help he memorized many details of regimental life so well that 30 of the dead man's brother officers were willing to swear that he was Sir Roger despite his extraordinary change in appearance.

He produced more than 100 witnesses who testified that he was the real Sir Roger. None was really close to the family, but they made a powerful showing against the 17 who spoke against him.

Inevitably, it was his rough way of speaking that condemned him. "I would have won if only I could have kept my mouth shut," he said later.

The case went on for 102 days and cost the Tichborne family 90,000 pounds. After losing the action, Orton was charged with perjury. He was jailed for 14 years.

Loyal supporters

Amazingly, the discredited Orton still had supporters. Dr. Kenealy, the lawyer who defended him, tried to turn the case into a national issue, and his vehement defense led to his being disbarred for unprofessional conduct.

Orton completed 10 years of his i4-year sentence and, after his release, arranged a tour of public meetings in a vain attempt to regain sympathy. He also worked at a music hall and later in a saloon and a tobacconist's shop. With poverty facing him, he sold his "confession" to the newspaper People for 3,000 pounds. But he still died penniless.

Even in death, Orton was able to inspire the belief of one unknown person, for there is an inscription on his grave: "Sir Roger Charles Doughty Tichborne; born 5 January 1829; died 1 April 1898."