Waiting for an invitation to arrive, going to a party where no one’s still alive. It’s a dead man’s party, who could ask for more? Everybody’s coming’, leave your body and soul at the door.” – Lyrics and photo from ‘Dead Man’s Party’ by Oingo Boingo from Wikipedia.

[Kindly punch this tune into your phone and listen to a little background music while reading the article].

The stark reality of death in the aftermath of battle necessitates burying the dead.

Burial work after the Battle of Gettysburg was quite the undertaking (pun intended), given the large number of dead (8,900) left on the field and an average of 50-100 men dying daily in the hospitals. An estimated 160,000 men descended on Gettysburg during the first four days of July 1863. One in three of these men were casualties. Thousands of wounded were crowded in every church, house, and barn for miles around. At the time of the battle, the population of Gettysburg numbered approximately 2,400 people. When the smoke cleared, the roll call of the dead greatly outnumbered the undead. One soldier referred to it as “being adrift in a carnival of death……truly it was a dead man’s party.”

Those who ventured out on the battlefield immediately after the carnage witnessed scenes straight out of a horror movie. Once seen, the horrors could not be unseen.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

As Lee’s army pulled out of Gettysburg through the night of July 4th, 1863, the townspeople and the Union burial parties ventured out to see the carnage. Death was everywhere. Debris littered the landscape for miles, and pieces of people and horses were far and wide. It was Independence Day 1863 in the United States, but for the people in Gettysburg – it was a Halloween horror show. The following paragraphs are derived from several eyewitness accounts and from the diaries of unnamed Union soldiers from New Jersey.

A Union soldier wrote, “The captain ordered us to stack arms and marched us out for burial detail. Like all things at this place, this was new to me. It was like going to a shindig for the dead. All over the fields, like sheaves bound by the reaper, dead bodies were everywhere. I kept thinking about how the dead all around greatly outnumbered the living. Their eyes were open, but they were stone dead. The fright was made intolerable when it got dark. Darkness plays tricks on your mind. My friend knew I was uneasy and took advantage of it. He lay down next to a corpse in the darkness and played dead. When I walked over, he sat up suddenly, sending me fleeing. Later he put his arm around me and dropped a severed limb in my lap. I was screaming mad. The whole place was unsettling. On several occasions, when we rolled a body over or picked one up an arm would raise, or the guts would spill out. I never wanted to be away from a place so much in my life.”

Reading these recollections conjures up images of zombies or a Stephen King horror movie. Another soldier wrote, “The dead lay wherever the battle had raged, or wherever their final steps had taken them. Some with faces bloated and blackened beyond recognition, many with glassy eyes staring up at you, others with faces downward and clenched hands filled with dirt, revealing the agony of their last moments. There were headless bodies and corpses with missing arms and legs and heads with faces torn off and heads with gaping holes showing brains. Several rebel soldiers lay impaled by shattered bones flying from the explosive disintegration of the men in front of them. Canister shot does terrible things to human bodies. The bodies were mangled in grotesque positions which often results from unbearable pain and suffering….and they were everywhere.”

Another wrote, “All around was the wreck the battle-storm left in its wake—broken caissons, dismounted guns, rifles bent and twisted by the storm of battle or dropped and scattered by severed hands; thousands of dead and bloated horses, torn and ragged equipment, and all the sorrowful wreck that the waves of battle left behind. But above all, hugging the earth like a fog, poisoning every breath, was the pestilential stench of decaying flesh.” The horror.

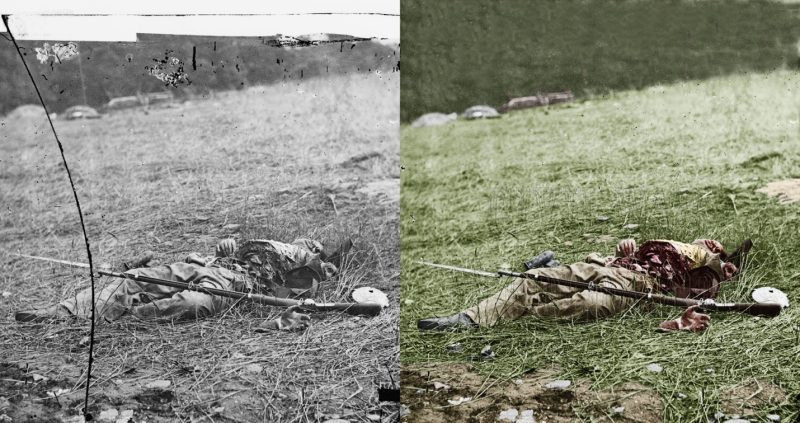

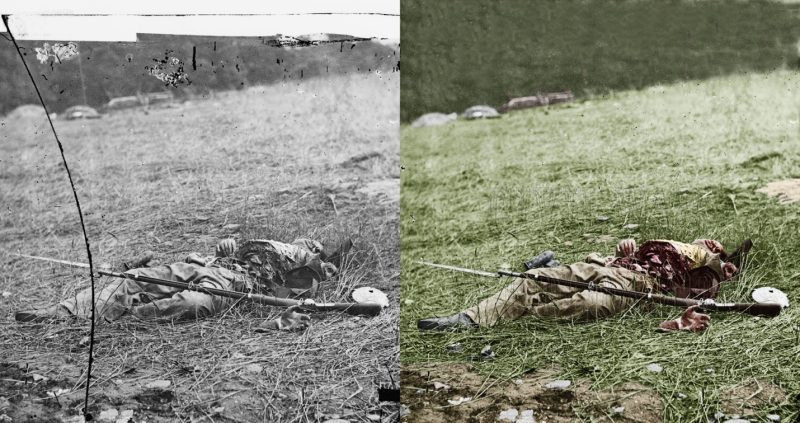

Original and colorized photo of a Union soldier blown apart by artillery lies dead on the ground at Gettysburg. Photo by Mathew Brady, taken from James F. Commons, Wikimedia

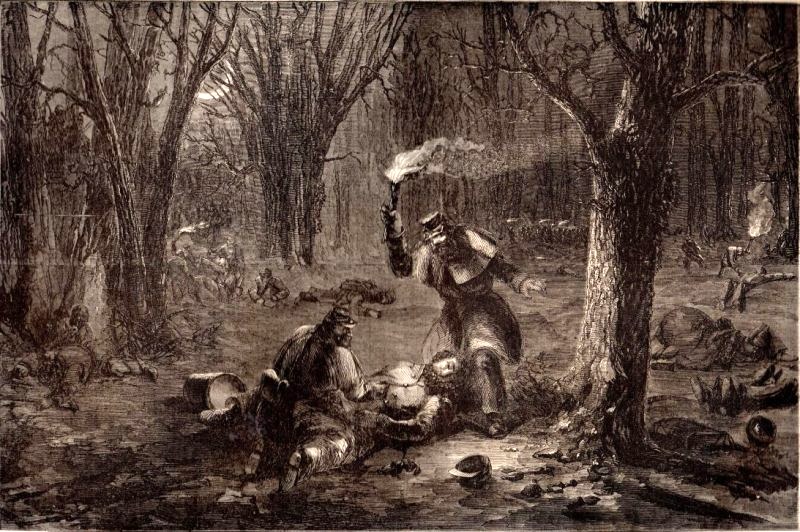

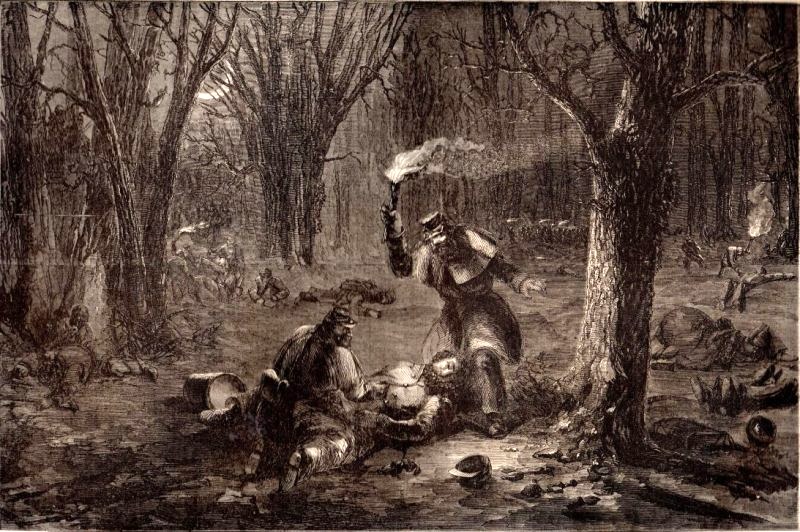

The first burial parties sent out at dusk on July 4th were instructed to stay out until midnight. They buried Union and Confederates alike wherever they had fallen. When night fell the soldiers used lanterns to find the dead. It was truly an eerie sight to see the lanterns moving about and adding depth to the darkness like giant fireflies in summer.

Night burials. One Union soldier wrote, “I was feeling my way around the battlefield after my lantern had suddenly gone out when I tripped and landed on a lump of cloth. When the lantern was relit and lifted, I realized I was laying on a corpse whose mouth was gaped wide open in agony, staring intensely into my face. It startled me so that I jumped up in fright and tripped over another corpse. I soon discovered the bodies of seventeen Union soldiers all around me. That sight is seared into my memory.”

In the first day or so after the battle, bodies were buried where they were found, regardless of blue or gray. However, in the subsequent days, when burials were more organized, burial parties consisted of three men. Two men carried the stretcher, and one man worked the pike pole to push the bodies onto the stretcher. Fence posts were used to scrape up bodies that were torn apart or badly decomposed. The dead were carried to a burial trench and laid out in lines or immediately placed in a trench. The heads of each soldier were placed in the same direction, and Confederate and Union soldiers were separated for burial.

The graves were shallow. Most graves were barely two feet deep. Trenches were typically constructed for 30 and 70 bodies. Some corpses were tied together for easier transportation or to offset the effects of rigor-mortis so that the bodies would be straight and flat, thus increasing the number of corpses per trench. According to local accounts, as weeks passed, it was not uncommon to see hands and feet sticking out of the ground after the rain washed the dirt from those shallow graves.

Private Robert Carter recollected that when “the bodies were slid into the trenches, (they) broke apart, to the horror and disgust of the whole party, and the stench still lingers in our nostrils. As many as ninety bodies were thus disposed of in one trench … most of them were tumbled in just as they fell with not a prayer, eulogy, or tear to distinguish them from the burial of animals.”

Time was crucial: The necessity of getting the bodies into the ground for health and sanitary reasons was coupled with the fact that the Union army was departing hurriedly in pursuit of General Lee’s retreat. The Union Army gradually pulled out of Gettysburg on July 5th & 6th, leaving local militia units and citizens to police up the battlefield. The departure of the army ushered in disorder. Occasionally at night, militia personnel had to chase off thieves, souvenir hunters, and deserters from pillaging the dead.

Once the military departed, only the citizens were left with the burial tasks. By July 11, 1863, most of the Union dead were interned.

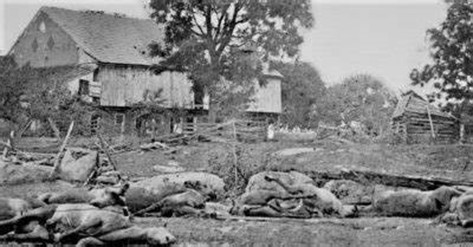

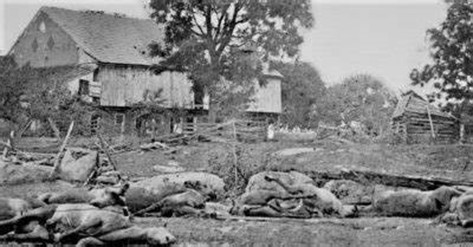

Note: Interestingly, that very day 50 miles south, General Meade and General Lee were at it again astride the Potomac River in Williamsport, MD. Two days later, Lee slipped across the river to safety in Virginia, and for historians and posterity, the Gettysburg campaign ended there. Meanwhile, back in the little town of Gettysburg, the wounded filled every dwelling, and the burials and searches continued. (Photo by Timothy H Sullivan, Library of Congress, depicting dead horses littering the farmhouse grounds).

The internment of the dead was more difficult in some areas of the battlefield. During the second, third, and fourth days of July, the Confederates had control of the town, so all the fields of battle from Day 1 were behind their positions. Apparently, the Confederates undertook no large-scale efforts to bury bodies. The decomposition of the bodies from the first two days of battle was much higher as they were exposed to the elements and animals longer. Most of these dead were inaccessible until the Confederates vanished during the darkness of July 4th. One of the more gruesome sights endured by the burial parties was Oak Hill. Stories from the aftermath of fighting there have lingered through the ages as a favorite ‘haunt’ among tourists.

Iverson’s Pits: The burial parties detailed out to the Oak Hill area of Seminary Ridge had quite the task. This was the scene of a virtual massacre days before. Hundreds of Confederate corpses had been subjected to searing July heat since July 1st and were not in good repair.

Here’s what happened: On July 1, 1863, the men of General Alfred Iverson’s North Carolina Brigade had arrived at Gettysburg and were preparing to outflank the Union First Corps at Oak Hill. This spot was the northernmost point of Seminary Ridge. They were formed into their line of battle and advanced toward a line of trees about 300 yards away.

Colorized photo by Alexander Gardner, Library of Congress, ‘Confederates gathered for burial in Gettysburg’

To their left front was a low stone wall, but no one paid it any attention. They believed that they were about to crash through the woods and roll up the flank of the Yankees on the other side. Suddenly, Federal soldiers rose and delivered a withering volley of fire into the unsuspecting rebels. Hundreds of North Carolinians fell in straight lines just as they had marched. Within minutes more than 900 of Iverson’s brigade lay dying in the grass. Those few who could still stand fled the field, leaving their wounded comrades behind.

As the battlefield migrated southeast of town, the Confederate army’s focus was elsewhere; hence no formal burial parties were dispatched to bury all these men. When the armies departed, the decomposition of the dead at Oak Hill was further along than most. Days after the battle ended, the decomposed bodies of the fallen were interred in rows of hastily dug trenches — virtually in the same spots where they fell. As time passed, the graves settled, visibly marking the field with sunken rows where the trenches had been dug.

Afterward, locals dubbed the grim spot “Iverson’s Pits.” For years, the people who worked the farm claimed the area was haunted, and several workers, terrorized by sightings, refused to venture anywhere near the area after sunset. Supernatural sightings of ghostly manifestations were common. According to Gettysburg folklore, sightings of Civil War soldiers walking around have been ongoing since the battle and persist to this day. Tourists can still see areas of sunken ground (Iverson’s Pits) that denote the locations of the burial trenches. Today, the Oak Hill area comprises Gettysburg’s most enduring ghost stories.

Photo of Gen. Iverson. After Gettysburg, Iverson endured the blame for the massacre & was dismissed from the Confederate Army and sent home in disgrace.

After Lee’s retreat, the Union held the field and were concerned mostly with the burial of their own. Most of the Confederate dead were placed in mass trenches. On Little Round Top, the terrain was not conducive to digging, so the Confederate bodies were piled into a valley and partially covered with rocks and brush. In the weeks and months to follow, locals recalled many ghoulish sightings of decomposed soldiers popping up in various locations – likely scattered about by animals. Finding decomposed corpses lying out in the open weeks after the fight probably enhanced the eerie stories for generations to come.

All and all, the task of burying the dead was daunting. Over the first twelve days of work, the total number of Confederates buried was roughly 4,803, with Union burials estimated at 3,905. The incredible loss of life from the U.S. Civil War affected all Americans, but the faces of death were especially engrained in the memory of those who lingered on battlefields after the last shots rang out. Sadly, the scenes of horror and burial parties played out again and again on numerous carnivals of death until the guns fell silent in the spring of 1865.

My wife's old boss's dad was captured at Gettysburg and was tasked burying the dead.

From his account the above is accurate.....In fact he escaped from the burial detail and made his way back to Virginia.

[Kindly punch this tune into your phone and listen to a little background music while reading the article].

The stark reality of death in the aftermath of battle necessitates burying the dead.

Burial work after the Battle of Gettysburg was quite the undertaking (pun intended), given the large number of dead (8,900) left on the field and an average of 50-100 men dying daily in the hospitals. An estimated 160,000 men descended on Gettysburg during the first four days of July 1863. One in three of these men were casualties. Thousands of wounded were crowded in every church, house, and barn for miles around. At the time of the battle, the population of Gettysburg numbered approximately 2,400 people. When the smoke cleared, the roll call of the dead greatly outnumbered the undead. One soldier referred to it as “being adrift in a carnival of death……truly it was a dead man’s party.”

Those who ventured out on the battlefield immediately after the carnage witnessed scenes straight out of a horror movie. Once seen, the horrors could not be unseen.

Courtesy of the Library of Congress.

As Lee’s army pulled out of Gettysburg through the night of July 4th, 1863, the townspeople and the Union burial parties ventured out to see the carnage. Death was everywhere. Debris littered the landscape for miles, and pieces of people and horses were far and wide. It was Independence Day 1863 in the United States, but for the people in Gettysburg – it was a Halloween horror show. The following paragraphs are derived from several eyewitness accounts and from the diaries of unnamed Union soldiers from New Jersey.

A Union soldier wrote, “The captain ordered us to stack arms and marched us out for burial detail. Like all things at this place, this was new to me. It was like going to a shindig for the dead. All over the fields, like sheaves bound by the reaper, dead bodies were everywhere. I kept thinking about how the dead all around greatly outnumbered the living. Their eyes were open, but they were stone dead. The fright was made intolerable when it got dark. Darkness plays tricks on your mind. My friend knew I was uneasy and took advantage of it. He lay down next to a corpse in the darkness and played dead. When I walked over, he sat up suddenly, sending me fleeing. Later he put his arm around me and dropped a severed limb in my lap. I was screaming mad. The whole place was unsettling. On several occasions, when we rolled a body over or picked one up an arm would raise, or the guts would spill out. I never wanted to be away from a place so much in my life.”

Reading these recollections conjures up images of zombies or a Stephen King horror movie. Another soldier wrote, “The dead lay wherever the battle had raged, or wherever their final steps had taken them. Some with faces bloated and blackened beyond recognition, many with glassy eyes staring up at you, others with faces downward and clenched hands filled with dirt, revealing the agony of their last moments. There were headless bodies and corpses with missing arms and legs and heads with faces torn off and heads with gaping holes showing brains. Several rebel soldiers lay impaled by shattered bones flying from the explosive disintegration of the men in front of them. Canister shot does terrible things to human bodies. The bodies were mangled in grotesque positions which often results from unbearable pain and suffering….and they were everywhere.”

Another wrote, “All around was the wreck the battle-storm left in its wake—broken caissons, dismounted guns, rifles bent and twisted by the storm of battle or dropped and scattered by severed hands; thousands of dead and bloated horses, torn and ragged equipment, and all the sorrowful wreck that the waves of battle left behind. But above all, hugging the earth like a fog, poisoning every breath, was the pestilential stench of decaying flesh.” The horror.

Original and colorized photo of a Union soldier blown apart by artillery lies dead on the ground at Gettysburg. Photo by Mathew Brady, taken from James F. Commons, Wikimedia

The first burial parties sent out at dusk on July 4th were instructed to stay out until midnight. They buried Union and Confederates alike wherever they had fallen. When night fell the soldiers used lanterns to find the dead. It was truly an eerie sight to see the lanterns moving about and adding depth to the darkness like giant fireflies in summer.

Night burials. One Union soldier wrote, “I was feeling my way around the battlefield after my lantern had suddenly gone out when I tripped and landed on a lump of cloth. When the lantern was relit and lifted, I realized I was laying on a corpse whose mouth was gaped wide open in agony, staring intensely into my face. It startled me so that I jumped up in fright and tripped over another corpse. I soon discovered the bodies of seventeen Union soldiers all around me. That sight is seared into my memory.”

In the first day or so after the battle, bodies were buried where they were found, regardless of blue or gray. However, in the subsequent days, when burials were more organized, burial parties consisted of three men. Two men carried the stretcher, and one man worked the pike pole to push the bodies onto the stretcher. Fence posts were used to scrape up bodies that were torn apart or badly decomposed. The dead were carried to a burial trench and laid out in lines or immediately placed in a trench. The heads of each soldier were placed in the same direction, and Confederate and Union soldiers were separated for burial.

The graves were shallow. Most graves were barely two feet deep. Trenches were typically constructed for 30 and 70 bodies. Some corpses were tied together for easier transportation or to offset the effects of rigor-mortis so that the bodies would be straight and flat, thus increasing the number of corpses per trench. According to local accounts, as weeks passed, it was not uncommon to see hands and feet sticking out of the ground after the rain washed the dirt from those shallow graves.

Private Robert Carter recollected that when “the bodies were slid into the trenches, (they) broke apart, to the horror and disgust of the whole party, and the stench still lingers in our nostrils. As many as ninety bodies were thus disposed of in one trench … most of them were tumbled in just as they fell with not a prayer, eulogy, or tear to distinguish them from the burial of animals.”

Time was crucial: The necessity of getting the bodies into the ground for health and sanitary reasons was coupled with the fact that the Union army was departing hurriedly in pursuit of General Lee’s retreat. The Union Army gradually pulled out of Gettysburg on July 5th & 6th, leaving local militia units and citizens to police up the battlefield. The departure of the army ushered in disorder. Occasionally at night, militia personnel had to chase off thieves, souvenir hunters, and deserters from pillaging the dead.

Once the military departed, only the citizens were left with the burial tasks. By July 11, 1863, most of the Union dead were interned.

Note: Interestingly, that very day 50 miles south, General Meade and General Lee were at it again astride the Potomac River in Williamsport, MD. Two days later, Lee slipped across the river to safety in Virginia, and for historians and posterity, the Gettysburg campaign ended there. Meanwhile, back in the little town of Gettysburg, the wounded filled every dwelling, and the burials and searches continued. (Photo by Timothy H Sullivan, Library of Congress, depicting dead horses littering the farmhouse grounds).

The internment of the dead was more difficult in some areas of the battlefield. During the second, third, and fourth days of July, the Confederates had control of the town, so all the fields of battle from Day 1 were behind their positions. Apparently, the Confederates undertook no large-scale efforts to bury bodies. The decomposition of the bodies from the first two days of battle was much higher as they were exposed to the elements and animals longer. Most of these dead were inaccessible until the Confederates vanished during the darkness of July 4th. One of the more gruesome sights endured by the burial parties was Oak Hill. Stories from the aftermath of fighting there have lingered through the ages as a favorite ‘haunt’ among tourists.

Iverson’s Pits: The burial parties detailed out to the Oak Hill area of Seminary Ridge had quite the task. This was the scene of a virtual massacre days before. Hundreds of Confederate corpses had been subjected to searing July heat since July 1st and were not in good repair.

Here’s what happened: On July 1, 1863, the men of General Alfred Iverson’s North Carolina Brigade had arrived at Gettysburg and were preparing to outflank the Union First Corps at Oak Hill. This spot was the northernmost point of Seminary Ridge. They were formed into their line of battle and advanced toward a line of trees about 300 yards away.

Colorized photo by Alexander Gardner, Library of Congress, ‘Confederates gathered for burial in Gettysburg’

To their left front was a low stone wall, but no one paid it any attention. They believed that they were about to crash through the woods and roll up the flank of the Yankees on the other side. Suddenly, Federal soldiers rose and delivered a withering volley of fire into the unsuspecting rebels. Hundreds of North Carolinians fell in straight lines just as they had marched. Within minutes more than 900 of Iverson’s brigade lay dying in the grass. Those few who could still stand fled the field, leaving their wounded comrades behind.

As the battlefield migrated southeast of town, the Confederate army’s focus was elsewhere; hence no formal burial parties were dispatched to bury all these men. When the armies departed, the decomposition of the dead at Oak Hill was further along than most. Days after the battle ended, the decomposed bodies of the fallen were interred in rows of hastily dug trenches — virtually in the same spots where they fell. As time passed, the graves settled, visibly marking the field with sunken rows where the trenches had been dug.

Afterward, locals dubbed the grim spot “Iverson’s Pits.” For years, the people who worked the farm claimed the area was haunted, and several workers, terrorized by sightings, refused to venture anywhere near the area after sunset. Supernatural sightings of ghostly manifestations were common. According to Gettysburg folklore, sightings of Civil War soldiers walking around have been ongoing since the battle and persist to this day. Tourists can still see areas of sunken ground (Iverson’s Pits) that denote the locations of the burial trenches. Today, the Oak Hill area comprises Gettysburg’s most enduring ghost stories.

Photo of Gen. Iverson. After Gettysburg, Iverson endured the blame for the massacre & was dismissed from the Confederate Army and sent home in disgrace.

After Lee’s retreat, the Union held the field and were concerned mostly with the burial of their own. Most of the Confederate dead were placed in mass trenches. On Little Round Top, the terrain was not conducive to digging, so the Confederate bodies were piled into a valley and partially covered with rocks and brush. In the weeks and months to follow, locals recalled many ghoulish sightings of decomposed soldiers popping up in various locations – likely scattered about by animals. Finding decomposed corpses lying out in the open weeks after the fight probably enhanced the eerie stories for generations to come.

All and all, the task of burying the dead was daunting. Over the first twelve days of work, the total number of Confederates buried was roughly 4,803, with Union burials estimated at 3,905. The incredible loss of life from the U.S. Civil War affected all Americans, but the faces of death were especially engrained in the memory of those who lingered on battlefields after the last shots rang out. Sadly, the scenes of horror and burial parties played out again and again on numerous carnivals of death until the guns fell silent in the spring of 1865.

My wife's old boss's dad was captured at Gettysburg and was tasked burying the dead.

From his account the above is accurate.....In fact he escaped from the burial detail and made his way back to Virginia.

Last edited: