CMike

Zionist, proud to be

- Oct 25, 2009

- 9,219

- 1,171

- 190

And the lies go on...

History & Overview of the USS Liberty Incident | Jewish Virtual Library

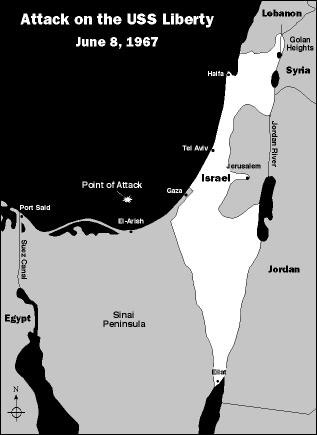

A U.S. spy plane was sent to the area as soon as the NSA learned of the attack on the Liberty and recorded the conversations of two Israeli Air Force helicopter pilots, which took place between 2:30 and 3:37 p.m. on June 8. The orders radioed to the pilots by their supervisor at the Hatzor base instructing them to search for Egyptian survivors from the “Egyptian warship” that had just been bombed were also recorded by the NSA. “Pay attention. The ship is now identified as Egyptian,” the pilots were informed. Nine minutes later, Hatzor told the pilots the ship was believed to be an Egyptian cargo ship. At 3:07, the pilots were first told the ship might not be Egyptian and were instructed to search for survivors and inform the base immediately the nationality of the first person they rescued. It was not until 3:12 that one of the pilots reported that he saw an American flag flying over the ship at which point he was instructed to verify if it was indeed a U.S. vessel.6

History & Overview of the USS Liberty Incident | Jewish Virtual Library

A U.S. spy plane was sent to the area as soon as the NSA learned of the attack on the Liberty and recorded the conversations of two Israeli Air Force helicopter pilots, which took place between 2:30 and 3:37 p.m. on June 8. The orders radioed to the pilots by their supervisor at the Hatzor base instructing them to search for Egyptian survivors from the “Egyptian warship” that had just been bombed were also recorded by the NSA. “Pay attention. The ship is now identified as Egyptian,” the pilots were informed. Nine minutes later, Hatzor told the pilots the ship was believed to be an Egyptian cargo ship. At 3:07, the pilots were first told the ship might not be Egyptian and were instructed to search for survivors and inform the base immediately the nationality of the first person they rescued. It was not until 3:12 that one of the pilots reported that he saw an American flag flying over the ship at which point he was instructed to verify if it was indeed a U.S. vessel.6