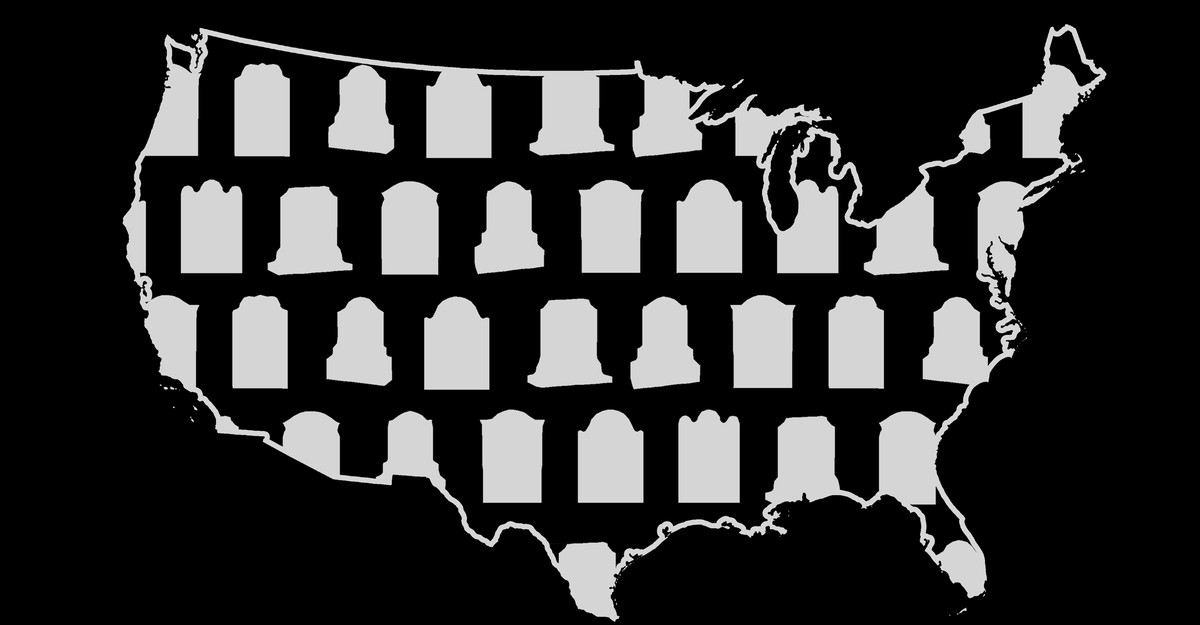

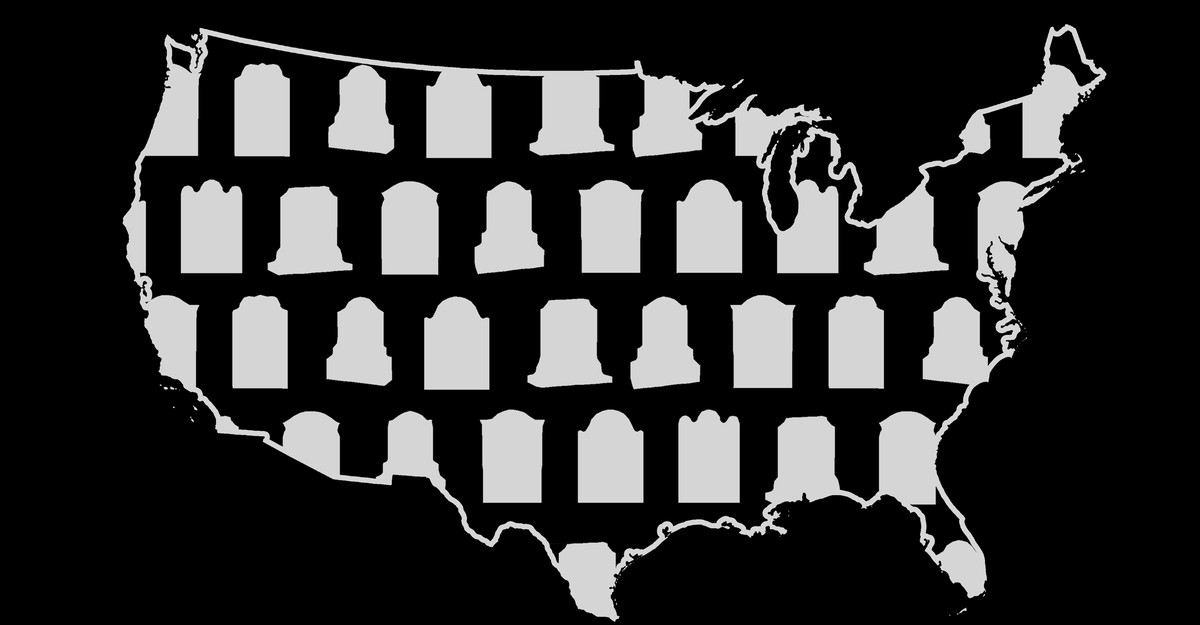

We’ve starved our public-health sector. The Costa Rica model demonstrates what happens when you put it first.

www.newyorker.com

From the piece:

"Life expectancy tends to track national income closely. Costa Rica has emerged as an exception. Searching a newer section of the cemetery that afternoon, I found only one grave for a child. Across all age cohorts, the country’s increase in health has far outpaced its increase in wealth. Although Costa Rica’s per-capita income is a sixth that of the United States—and its per-capita health-care costs are a fraction of ours—life expectancy there is approaching eighty-one years. In the United States, life expectancy peaked at just under seventy-nine years, in 2014, and has declined since."

Why?

Here is why.

"So when did Costa Rica’s results diverge from others’? That started in the early nineteen-seventies: the country adopted a national health plan, which broadened the health-care coverage provided by its social-security system, and a rural health program, which brought the kind of medical services that the cities had to the rest of the country. Atenas finally got a primary-care clinic. “With two or three doctors,” Salas recalled. “With five nurses. With social workers. For everything.” In 1973, the social-security administration was charged with upgrading the hospital system, including in Alajuela and other rural regions. In this early period, the country spent more of its G.D.P. on the health of its people than did other countries of similar income levels—and, indeed, more than some richer ones. But what set Costa Rica apart wasn’t simply the amount it spent on health care. It was how the money was spent: targeting the most readily preventable kinds of death and disability.

That may sound like common sense. But medical systems seldom focus on any overarching outcome for the communities they serve. We doctors are reactive. We wait to see who arrives at our office and try to help out with their “chief complaint.” We move on to the next person’s chief complaint: What seems to be the problem? We don’t ask what our town’s most important health needs are, let alone make a concerted effort to tackle them. If we were oriented toward public health, we would have been in touch with all our patients, if not everyone in the communities we serve, to schedule appointments for vaccination against the coronavirus, the No. 3 killer in the past year. We would have coördinated with public-health officials to prevent cardiovascular disease, the No. 1 killer, by jointly taking aim at high blood pressure and cholesterol, smoking, and dietary salt intake. We would have made a priority of preventing disease, rather than just treating it. But we haven’t."

It continues:

"

I saw this reliability throughout our visits. Because everyone was enrolled with an ebais, everyone was contacted individually about a covid vaccination appointment—most at their neighborhood clinic and a few at home. One woman I met explained that she’d learned about her appointment by phone. I asked her what would happen if the ebais folks didn’t call. She looked at me puzzled. Maybe something was lost in translation. She repeated that she knew what week they would call, and they called. I persisted: What if they didn’t? She’d wait a couple of days and call herself, she said. It was no big deal

. She asked me how things worked where I was from. I could only sigh."

If that happened here...the health department would be sued for calling someone.

Finally...

"She wants all the members of her teams to understand that their priority is “the relationship with the community, not just between the physician and patient.” This, she said, is the foundation of the ebaissystem. There are critical services that have to reach everyone in the community at every stage of life, she explained. Children have regular pediatric visits, starting from the first days of life. Pregnant women have their prenatal and postnatal checks. All adults have tests and follow-up visits to prevent and treat everything from iron deficiency to H.I.V. It’s all free. If people don’t show up for their appointments, she makes sure their team finds out why and figures out what can be done."

I'm set for retirement in less than a decade. Costa Rica may be a good place to spend my sunset years....

www.theatlantic.com

www.theatlantic.com