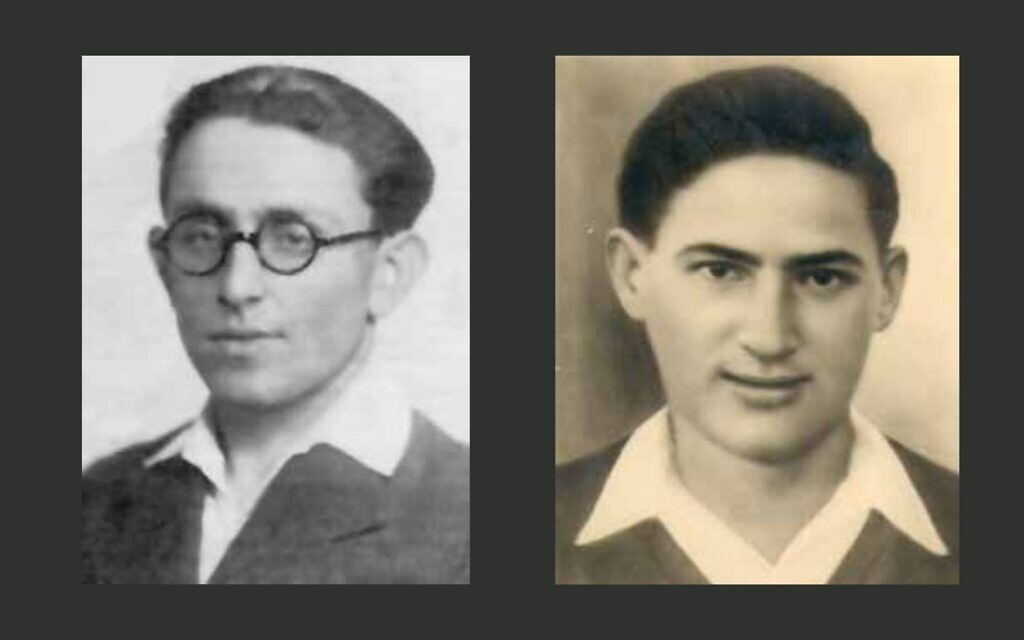

Trotsky’s life before the revolution is more instructive of the networks of Jewish Bolsheviks. Arrested in 1906, he was sent into exile by the tsarist state. He escaped and made his way to Vienna, where he became friends with Adolph Joffe. Joffe came from a family of Jewish Crimean Karaites and became an editor of Pravda. Close friends for the rest of their lives, they opposed the more lenient attitude of their fellow Jews Kamanev and Zinoviev on the Central Committee in 1917, opposing the inclusion of other socialist parties in the government that emerged after the revolution. Trotsky was expelled from the Central Committee in 1927 along with Zinoviev. He went into exile in 1929 and was assassinated on Stalin’s orders in 1940. Joffe committed suicide in 1927; his wife Maria and daughter Nadezhda were arrested and sent to labor camps and were not released until after Stalin’s death in 1953.

Late in life, as many thousands of Jews were being executed in the purges by Stalin, not as Jews but as leading communists, Trotsky penned several thoughts on Jewish issues. He said that in his early days, “I rather leaned toward the prognosis that the Jews of different countries would be assimilated and that the Jewish question would thus disappear.” He argued, “Since 1925 and above all since 1926, antisemitic demagogy – well camouflaged, unattackable – goes hand in hand with symbolic trials.” He accused the USSR of insinuating that Jews were “internationalists” during show trials.

The Central Committee of the USSR is instructive as an indicator of the prominence of Jews in leadership positions. In the Sixth Congress of the Bolshevik Russian Social Democratic Labor Party and its Central Committee elected in August 1917, we find that five of the committee’s 21 members were Jewish. This included Trotsky, Zinoviev, Moisei Uritsky, Sverdlov and Grigori Sokolnikov. Except for Sverdlov, they were all from Ukraine. The next year they were joined by Kamenev and Radek. Jews made up 20% of the central committees until 1921, when there were no Jews on this leading governing body.

The high percentage of Jews in governing circles in these early years matched their percentage in urban environments, politburo member Sergo Ordzhonikidze told the 15th Congress of the party, according to Solzhenitsyn. Most Jews lived in towns and cities due to urbanization and laws that had kept them off the land.

Jewish membership in top circles continued to decline in the 1920s. By the 11th Congress, only Lazar Kaganovich was elected to the Central Committee in 1922 alongside 26 other members. Subsequently few Jews served in these leadership positions. In 1925 there were four Jews out of 63 members. Like the rest of their comrades, almost all of them were killed in the purges. Others elected in 1927 and 1930 were shot as well, including Grigory Kaminsky, who came from a family of blacksmiths in Ukraine. With the exception of Lev Mekhlis and Kaganovich, few senior communist Jews survived the purges.

During the 1936 Moscow Trials, numerous defendants were Jewish. Of one group of 16 high-profile communists at a show trial, besides Kamenev and Zinoviev, names like Yefim Dreitzer, Isak Reingold, Moissei and Nathan Lurye and Konon Berman-Yurin ring out as Jewish. In a twisted irony, some of these Bolsheviks who had played a prominent role executing others, such as NKVD Director Genrikh Yagoda, were themselves executed. Solzhenitsyn estimates that Jews in leading positions went from a high of 50% in some sectors to 6%. Many Jewish officers in the Red Army also suffered in the purges. Millions of Jews would remain in Soviet territories, but they would never again obtain such prominent positions in the USSR.

In a July 1940 letter, Trotsky imagined that future military events in the Middle East “may well transform Palestine into a bloody trap for several hundred thousand Jews.” He was wrong; it was the Soviet Union that was a bloody trap for many of those Jews who had seen salvation in communism and thought that by total assimilation and working for a zealous greater good they would succeed.

Instead, many ended up being murdered by the system they helped create.

WITH 100 years of hindsight it is still difficult to understand what attracted so many Jews to communism in the Russian empire. Were their actions infused with Jewishness, a sense of Jewish mission like the tikkun olam and “light unto the nations” values we hear about today, or were their actions strictly pragmatic as a minority group struggling to be part of larger society? The answer lies somewhere in the middle.

Many Jews made pragmatic economic choices to leave for the New World when facing discrimination and poverty. Others chose to express themselves as Jews first, either through Jewish socialist groups or Zionism. Still others struggled for equality in the empire, so they could remain Jews and be equal. One group sought a radical solution to their and society’s predicament, a communist revolution, and one that would not include other voices such as the Bund or Mensheviks, but solely that of their party. They had no compunction at murdering their coreligionists. They were not more or less ethical than their non-Jewish peers. How can we explain their disproportionate presence in the leadership of the revolution? It would be as if the Druse minority in Israel made up half of Benjamin Netanyahu’s cabinet, or Armenians were half of Emmanuel Macron’s government in France.

Perhaps the only way to understand some of it is to recognize that at Nelson Mandela’s 1963 Rivonia trial in South Africa five of the 13 arrested were Jewish, as were around one quarter of the 1960s Freedom Riders in the US. The 20th century was a century of Jewish activism, often for non-Jewish causes and often without an outwardly “Jewish” context. The Freedom Riders didn’t go as a “Jewish voice for African- Americans,” they went as activists for civil rights.

We prize minorities today who act for social justice as minorities, but the 20th century required a more nuanced approach. The situation Jews were born into in the 19th-century Pale of Settlement has no parallel with today’s Jewish experience. But despite economic hardship there was a spark in this community amidst unique circumstances of radical change that impelled it forward to leadership in numerous sectors in Russia and abroad.

(full article online)

A hundred years after the Bolsheviks swept to power, historians and contemporaries still struggle to understand the prominent role played by Jews.

www.jpost.com

elderofziyon.blogspot.com