Both sides accuse the other.

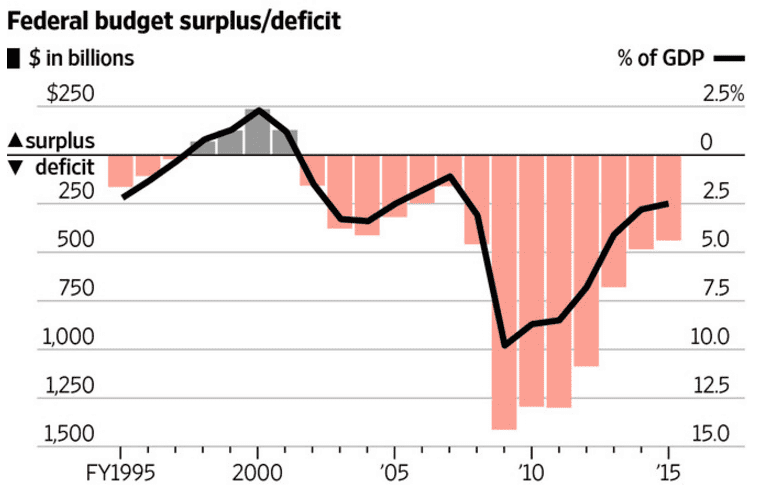

The Democrats accuse the Republicans of irresponsibly cutting taxes and spending but massively increasing the national debt.

The Republicans accuse the Democrats of irresponsibly increasing taxes and spending and massively increasing the national debt.

So which is it? Does cutting taxes and spending increase the debt? Or does more taxes and spending increase the debt?

And what is most important? Spending on what is considered important? Or the debt?

How much national debt can we stand?

And what, if anything, should be done about it? Can be done about it?

Macroeconomists are divided on the matter of debt and the role it plays in an economy and what be impacts of that role. There are strong arguments on each side of the matter. The questions posed in the OP, however, are not new; they are the very questions asked in every basic economics class.

I'm not going to discuss the answer personally; plenty of others have already done so. Read the linked paper, "

Government Debt," to get a comprehensive view of both sides of the topic and form whatever opinion most appeals to you.

Like everyone who thinks about politics and economics, I'm required sooner or later to take a position about the roles and impact of government debt. Because there is no clear consensus among economists, and because I have not invented any macroeconomic models of my own, nor have I the training needed to do so, and because I see the merit in both sides of the argument, I find it more useful to choose a stance based on what I know to be the body of consequences wrought by the nation's assuming greater and lesser amounts of debt and debt spending.

Some of the things I keep in mind when considering the matter are:

- The U.S. government is not an individual; therefore, debt assumed by the government plays a very different role than debt assumed by a person or company. First and foremost, unlike me and my firm, the government can print money to pay its debts. While it cannot do that with abandon, it can do it to some extent before the nation's creditors will deem it unacceptable. That a nation can do that, no matter how detrimental it may be to actually do that, is never far from the minds of creditors.

- By the same token some of the same rules that apply to you and me also apply to the government. For example, a dollar now is worth more than a dollar in the future; thus if the sum one must pay is fixed (either by interest rate or in total), it makes financial (as contrasted with economic) sense to pay for "whatever" we obtain/use/do now with dollars earned/collected in the future. Put another way, debt spending is what maximizes the taxpayers' money.

- Much of what the government buys doesn't have an immediate empirically measureable value. That's hugely different from what you, I and companies buy. For example, when a company spends X dollars to buy a piece of equipment, it can use the price of the equipment along with the annual revenue streams, interest on invested cash, debt on borrowings, etc. to calculate how much is too much to spend on the item, what is a good price to seek in negotiations, etc. The government, on the other hand, cannot necessarily so "cleanly" quantify the return on its expenditures.

In light of the preceding remarks, the nature and extent of debt the U.S. carries, or more precisely, what I think about it, has more to do with whether we need to carry/assume the debt we do in order to accomplish the things I feel we as a nation should or should not accomplish. Consequently, what I think about the national debt and its size does not depend purely on economic principles.

Do I think the current levels of debt the U.S. carries are problem today or will be in the next lustrum? Largely no. I will think it's a problem when the U.S. economy, and therefore revenue, actually stops growing. I think of it much as I consider financial position. If one earns $100K/year after taxes, how much debt can you reasonably handle? Could you afford a 30 year mortgage on a $600K home (assuming interest rates comparable to what the U.S. pays in its debt), for example? Clearly one can. That's another way in which the U.S.' debt is similar to yours or mine. The national debt is ~$18 trillion which is about six times the government's income.

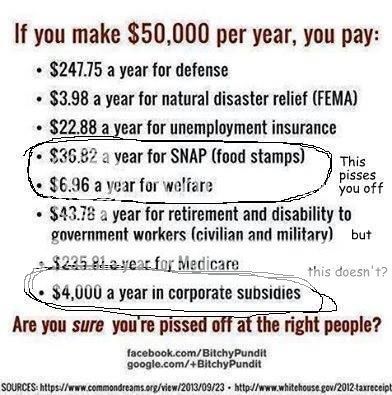

Let's take a simple example, one I'm using solely for the sake of the availability of data and to illustrate the nature of "hard to quantify" returns: food stamps. For each tax dollar spend on providing food stamps, the return to the U.S. economy is ~$1.70. Given that, does it make more sense to spend one's own money today or borrow someone else's money in order to provide a food stamp? It doesn't take a financial wizard to realize that even after paying interest on a borrowed dollar to buy a food stamp, that one is going to have a net gain not a net loss. Quite simply, there is no other use of that same dollar that can obtain guaranteed returns of ~70% or anything close to it. Thus it makes more sense to spend the dollar on a food stamp than on something else.

Of course, with food stamps, there's a limit. If "everyone" stops working, then nobody can be given a food stamp. However, as long as the proportion of the population needing food stamps is small enough (

i.e., the economy is growing, which is not what it'd do if "everyone" needed a food stamp), the government spending a dollar on a food stamp provides the best long term return on the use of that dollar. Therefore, if a food stamp were the only thing causing the country to borrow money, it'd make more sense to borrow the money and give the food stamp than it would to not so do.

So you see, my answer given above, that I'm okay with the debt as it and the nation stand now and for the foreseeable future, is what I think now. I may think something different a lustrum or decade from now. There is no single/simple answer that is the "right" answer for all time.