Ancient Jerusalem: The Village, the Town, the City

Ancient Jerusalem made such an enormous impact on Western civilization that it’s hard to fathom how small its population really was.

Excerpt:

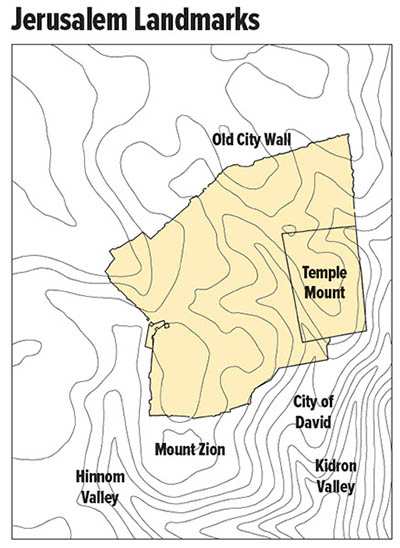

The first period that Geva considers in his study is from the 18th–11th centuries B.C.E. (Middle Bronze Age II to Iron Age I, in archaeological terms), the period before the arrival of the Israelites. Jerusalem was then confined to the small spur south of the Temple Mount known today as the City of David. As Geva reminds us, even then Jerusalem “was the center of an important territorial entity.”

From this period, the area includes a massive fortification system that has recently been excavated. Overall, however, the area comprises only about 11–12 acres. Geva estimates the population of the city during this period at between 500 and 700 “at most.” (Previously other prominent scholars had estimated Jerusalem’s population in this period as 880–1,100, 1,000, 2,500, 3,000; still this is hardly what we would consider a metropolis.)

The shaded area reflects the current walled Old City of Jerusalem.

The next period Geva considers is the period of the United Monarchy, the time of King David and King Solomon and a couple centuries thereafter (1000 B.C.E. down to about the eighth century B.C.E.). In David’s time, the borders of the city did not change from the previous period.

However, King Solomon expanded the confines of the city northward to include the Temple Mount. This increased the size of the city to about 40 acres, but the increase in population was not proportionate since much of this expansion was taken up with the Temple and royal buildings. “It is likely that Jerusalem attracted new inhabitants of different social classes,” Geva tells us. “Some of these people came to reside in the city as a consequence of their official and religious capacities, while others came to seek a livelihood in its developing economy.” Geva estimates the population of the city at this time at about 2,000. (Previously, other scholars had estimated the number of people living in the city at this time as 2,000, 2,500 or 4,500–5,000.)

In the mid-eighth century B.C.E., the area usually referred to as the Western Hill was added to the city of Jerusalem. This area is well documented archaeologically. With this addition, more than a hundred acres were added to the city, and the population of the city increased proportionately. According to some scholars, this increase may have been at least in part due to the influx of refugees from the north after the Assyrian conquest of the northern kingdom of Israel in 721 B.C.E.

By the end of the First Temple period (the First Temple was destroyed by the Babylonians in 586 B.C.E.), the walled city of Jerusalem covered 160 acres. By that time, settlement also extended northward outside the city walls, all of which expanded the city further. At its height, the population of Jerusalem at the end of the eighth century B.C.E., according to Geva, was 8,000.

As a result of the siege of Jerusalem by the Assyrian monarch Sennacherib in 701 B.C.E., Jerusalem’s population declined to about 6,000, and so it remained until the Babylonians destroyed the city in 586 B.C.E. and forced much of its population into exile in Babylon.

Other population estimates of Jerusalem during the nearly 200 years before the Babylonian destruction vary widely—partially because they focus on different time periods. Geva’s estimate is carefully grounded in archaeological data.

After the Babylonian destruction, the few inhabitants who remained in the city (or who returned) lived primarily in the old area of the City of David. After the Persians wrested control of Jerusalem from the Babylonians and even after Jerusalem became the capital of the Persian province of Yehud, Jerusalem continued to be confined to the spur known as the City of David with an estimated population of about a thousand people on 40 acres. (Geva calls it “minute.” Israel Finkelstein of Tel Aviv University puts the number even lower: 400 to 500.)

continued