TakeAStepBack

Gold Member

- Mar 29, 2011

- 13,935

- 1,742

- 245

[ame="http://www.amazon.com/gp/product/1591844495/ref=as_li_tf_tl?ie=UTF8&tag=misesinsti-20&linkCode=as2&camp=1789&creative=9325&creativeASIN=1591844495"]Currency Wars: The Making of the Next Global Crisis[/ame]

Book Description

Mises Daily: Tuesday, January 31, 2012 by Doug French

Looks like an excellent book. Doug French did a nice job putting this one and rothbard's book together here. I'll be picking this one up later today.

Book Description

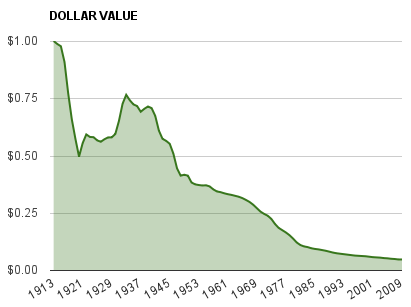

In 1971, President Nixon imposed national price controls and took the United States off the gold standard, an extreme measure intended to end an ongoing currency war that had destroyed faith in the U.S. dollar. Today we are engaged in a new currency war, and this time the consequences will be far worse than those that confronted Nixon.

Currency wars are one of the most destructive and feared outcomes in international economics. At best, they offer the sorry spectacle of countries' stealing growth from their trading partners. At worst, they degenerate into sequential bouts of inflation, recession, retaliation, and sometimes actual violence. Left unchecked, the next currency war could lead to a crisis worse than the panic of 2008.

Currency wars have happened before-twice in the last century alone-and they always end badly. Time and again, paper currencies have collapsed, assets have been frozen, gold has been confiscated, and capital controls have been imposed. And the next crash is overdue. Recent headlines about the debasement of the dollar, bailouts in Greece and Ireland, and Chinese currency manipulation are all indicators of the growing conflict.

As James Rickards argues in Currency Wars, this is more than just a concern for economists and investors. The United States is facing serious threats to its national security, from clandestine gold purchases by China to the hidden agendas of sovereign wealth funds. Greater than any single threat is the very real danger of the collapse of the dollar itself.

Baffling to many observers is the rank failure of economists to foresee or prevent the economic catastrophes of recent years. Not only have their theories failed to prevent calamity, they are making the currency wars worse. The U. S. Federal Reserve has engaged in the greatest gamble in the history of finance, a sustained effort to stimulate the economy by printing money on a trillion-dollar scale. Its solutions present hidden new dangers while resolving none of the current dilemmas.

While the outcome of the new currency war is not yet certain, some version of the worst-case scenario is almost inevitable if U.S. and world economic leaders fail to learn from the mistakes of their predecessors. Rickards untangles the web of failed paradigms, wishful thinking, and arrogance driving current public policy and points the way toward a more informed and effective course of action.

Mises Daily: Tuesday, January 31, 2012 by Doug French

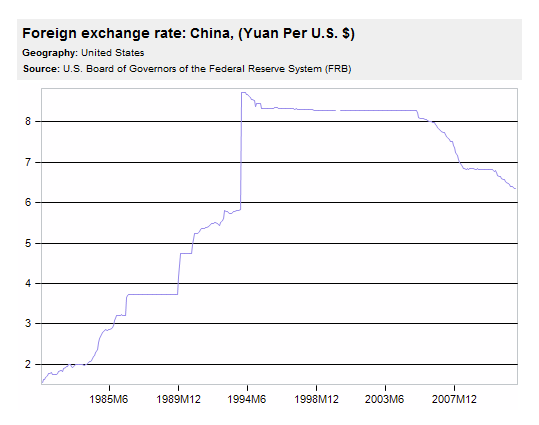

The talk is all about jobs, jobs, jobs in Washington and on the campaign trail as the unemployment rate continues to be elevated and long-term unemployment is higher than ever. Since getting government out of the way isn't an option, late last year congressional leaders decided to turn up the volume while crying that American workers are being damaged by China's undervalued currency — the renminbi (or yuan).

Bipartisan support was summoned to declare China a currency manipulator, triggering retaliatory tariffs on Chinese imports in hopes that China would allow the renminbi to rise against the dollar.

Scott Paul, who heads the Alliance for American Manufacturing, told American Public Media, "If we were able to revalue the yuan, it would make our exports substantially more competitive, not only in China but also globally."

But the Obama administration declined to finger China as a manipulator, causing a frustrated Mr. Paul to lament, "I'm disappointed that President Obama has now formally refused six times to cite China for its currency manipulation, a practice which has contributed to the loss of hundreds of thousands of American manufacturing jobs."

During the debates and on the campaign trail Republican presidential contender Mitt Romney has said repeatedly he would cite China for manipulating its currency the first day he takes office.

Reasonable people tend to tune out the Washington noise — rightly believing most of it is meaningless grandstanding. But the continued hectoring in China's direction is likely not so harmless. Combined with the Federal Reserve's stated policy to keep interest rates at virtually zero until the end of 2014, these are the sounds of Currency War III (CWIII) in its initial stages.

The big picture is that governments inevitably reduce the value of their currencies to their intrinsic value. But in the meantime, politicians are looking for votes, and governments look for advantage over competing governments. It is not just rockets and bombs that are fired; war is raged on the economic front, with currency manipulation as the primary weapon.

Before chronicling CWI and CWII, Rickards tells of participating in a war-games exercise at the Applied Physics Lab located between DC and Baltimore. There were no simulated missile launches or ground assaults in this mock battle; the only weapons used were financial — currencies, stocks, bonds, and derivatives.

Almost all the participants had military and think-tank backgrounds, with the only Wall Street types being the author and a couple of guys he recruited.

When the Russian team floated the idea for a gold-backed currency, threatening the dollar's status, one of Rickards's teammates, described by the author as "our Harvard guy," couldn't grasp the implications of the Russian move. "Gold is irrelevant to trade and international monetary policy," sniffed the Ivy Leaguer. "It's just a dumb idea and a waste of time."

Despite it being a war-games exercise, the administrative cell even declared Russia's gold move "illegal." Rickards reminded the participants that it was not so long ago that the world had gold-backed currencies and the move was then reconsidered and deemed merely "ill-advised."

When the Drudge Report featured Vladimir Putin calling for a gold-backed alternative to the dollar the following morning, Rickards and his guys were vindicated, but the academics remained unconvinced of gold's relevance.

The author explains that while currency wars are fought on the world stage, they begin with a domestic economy lacking in growth, with high unemployment, a weak banking sector, and worsening public finances. With economic growth stymied, time and time again, countries look to depreciate their currencies to promote export growth and investment.

Many historians mistakenly describe much of the period from 1870 to 1914 as a deflationary dark age. Rickards doesn't fall into that trap. He explains that this period of the classical gold standard was marked by gently falling prices leading to increased productivity, raised living standards, and the first glimpses of globalization.

The classical gold standard, besides being self-equilibrating, operated like a club, with members strictly adhering to the unwritten but well-understood rules. Free-market forces prevailed; government interventions were minimal; exchange rates were stable; and there was no US central bank to mess up monetary matters.

This monetary tranquility was jarred with the creation of the Federal Reserve in 1913. In Currency Wars, Rickards leans to the standard story that the Panic of 1907 gave rise to the Fed's creation, but, as Murray Rothbard explained in his History of Money and Banking in the United States: The Colonial Era to World War II,the Federal Reserve Act was just a part of the wave of legislation brought about by the Progressive movement.

Big business was tired of competing and continually innovating to stay ahead of falling prices. Business would much rather use the power of government to establish and maintain cartels in an effort to ensure high profits. The plan was "to transform the economy from roughly laissez-faire to centralized and coordinated statism," wrote Rothbard.

And while Rickards is right in noting that America has a long history of hating central banks, a movement by the Washington and financial elites to form what was to become the Federal Reserve System was actually started with the Indianapolis Monetary Convention in 1896. The 1907 panic added fuel to the fire, but much of the political groundwork was already laid.

What Rickards calls Currency War I began with the German hyperinflation in 1921 and ended with France breaking with gold in 1936 at the same time England was devaluing the pound sterling. In between were continuous monetary fireworks.

Austrian-leaning moviegoers who've seen Woody Allen's Oscar-nominated Midnight in Paris and wonder how or why an amazing collection of literary and creative US expatriates ended up in Paris in the mid-1920s won't be surprised to learn that there is an economic answer. Rickards explains that the French franc collapsed in 1923 allowing Ernest Hemingway, Scott and Zelda Fitzgerald, and Gertrude Stein to afford comfortable lifestyles in Paris converting their dollars from home.

The classic gold standard was long gone, replaced by a deeply flawed gold-exchange standard that allowed centrals banks to inflate, causing the boom of the 1920s and therefore the required correction of the 1930s exacerbated by government policy. FDR started his term in office by closing banks and then confiscating the people's gold. The language of FDR's order is chilling, giving citizens until May 1, 1933, to deliver to the Federal Reserve System "all gold coin, gold bullion and gold certificates now owned by them" with the threat of a $10,000 fine or ten years in prison.

Citizens received $20.67 per ounce from the government, only to watch their new president move the price up to $35 an ounce over three months — a 70 percent devaluation.

Rickards places Currency War II from 1967 to 1987. In between CWI and CWII was the Bretton Woods era, described by the author as a period of "currency stability, low inflation, low unemployment, high growth and rising income."

But as Henry Hazlitt and Jacques Rueff predicted, the phony gold-standard scheme created by John Maynard Keynes unraveled, setting the stage for CWII.

CWII began with a number of crises in the British sterling, and then a flight from the dollar into gold, with French president Charles de Gaulle calling for a return to the gold standard. The French president "helpfully offered to send the French navy to the United States to ferry the gold back to France."

This all led up to Richard Nixon preempting Hoss and Little Joe on August 15, 1971, telling the nation he was closing the gold window. The president blamed international speculators for having to interrupt America's favorite TV program, but money printing and budget deficits were to blame. Nixon also instituted a 10 percent surtax on all imports, effectively devaluing the dollar in the trade arena.

The devaluation was to spur employment, but within two years the United States was mired in recession. The United States suffered three recessions from 1973 to 1981, while purchasing power dropped by half from 1977 to 1981. Suddenly, "stagflation" was on the tip of everyone's tongue.

Paul Volcker took over as Fed chairman and quickly hiked interest rates, looking to stop the price inflation. The price of gold collapsed along with the inflation rate, and the dollar strengthened. According to Rickards, both Volcker and Ronald Reagan should be given credit for the dollar's turnaround.

But dollar strength finally got in the way of export jobs and the Plaza Accord of September 1985 was an attempt to drive down the greenback's value primarily against the yen and the mark. And it worked, from 1985 to 1988; the dollar fell 40 percent against the French franc, was cut in half against the yen, and fell 20 percent against the mark.

However, the devaluation did little for the US economy, and by 1987 monetary authorities met in Paris at the Louvre. The Louvre Accord was hatched to stop the dollar's fall. The Bank of Japan's willingness to expand its money supply to depreciate the yen would fuel one of the biggest stock-market bubbles of all time, with the Nikkei stock average roaring from around 10,000 in 1985 to a peak of 38,957.44 on December 29, 1989. More than two decades hence, that market still hasn't recovered.

Currency War III has just begun, and the author contends that, in addition to national issuers of currency, participants also include the IMF, the World Bank, the United Nations, hedge funds, global corporations, and private family offices of the super rich. After 40 years of massive money printing and explosion of derivatives, CWIII will be fought on a massive scale, with a real risk of a collapse of the entire monetary system.

So how's this currency war to end all currency wars going to turn out? The author paints a scary picture, using complexity theory and behavioral economics. Although the framework is different, the results follow Ludwig von Mises's outline of the three stages of inflation.

In Mises's stage one, government prints all the money it can, because prices don't rise nearly as much as money supply. In stage two, the demand for money falls, which intensifies price inflation. Finally, in stage three, prices go up faster than money supply. A shortage of money develops, and people urge government to print more; when the government does this, prices and money supply spiral upwards.

Rickards develops hypothetical thresholds wherein the dollar is repudiated. Up to an uncertain number, people can begin to repudiate the dollar to no effect on prices or the dollar's value. But once a critical threshold is passed, the collapse is triggered — as Hemingway once wrote about how bankruptcy happens — first slowly, then all at once.

A small change in preferences among just a few people could lead to a collapse, because the financial framework is a weakly constructed Keynesian contraption of fiat money and government deficits. Any one of thousands of events could trigger the collapse, and, as the author notes, the last straw will not be known until after the fact.

Rickards explores four potential outcomes for the dollar: multiple reserve currencies, special drawing rights, gold, and chaos. For those interested in how much the price of gold would have to be, under various gold-coverage ratios to different monetary aggregates, this part of the book is especially interesting, reminding me of what Murray Rothbard used to say to those claiming there wasn't enough gold in the world to have a gold standard. "You could have a gold standard with a single ounce," he said. It's not about the amount; it's about price.

Rickards comes to a price of $7,500 an ounce, far above today's price. But as the author points out, the change in the value of the dollar "has already occurred in substance. It simply has not been recognized by markets, central banks or economists."

Inevitably, chaos is the most likely outcome of the latest currency war, and while the author sketches out possible scenarios for how it might play out, no one really knows. Suffice it to say, it won't be pretty. Unfortunately, a currency war is neither a spectator sport nor a game. We all have to participate, and do our best to survive.

Looks like an excellent book. Doug French did a nice job putting this one and rothbard's book together here. I'll be picking this one up later today.

Last edited:

What?!! Is that a joke?

What?!! Is that a joke?