For the first time, scientists have tracked the source of a "fast radio burst" - a fleeting explosion of radio waves which, in this case, came from a galaxy six billion light-years away. The cause of the big flash, only the seventeenth ever detected, remains a puzzle, but spotting a host galaxy is a key moment in the study of such bursts. It also allowed the team to measure how much matter got in the way of the waves and thus to "weigh the Universe". Their findings are published in Nature.

Wake-up call

Fast radio bursts last only milliseconds but in that moment, whatever makes them blasts as much energy into space - in the form of radio waves - as our Sun emits in days or even weeks. To follow this particular signal home, an international team did rapid detective work with multiple telescopes and ultimately snapped an image of the source galaxy in visible light. Lead author Evan Keane had set up an alert system to trigger this flurry of activity, by running live data from the Parkes Radio Telescope in Australia directly into a supercomputer. "The goal was to reduce the lag from the thing hitting the dish, to us knowing that it hit the dish, from months - to nothing," he told the BBC.

Sure enough, when one of these mysterious bursts hit Parkes' famous 64m dish on April 18 2015, alarm bells rang and emails quickly circled the planet. By way of contrast, the first fast radio burst (FRB) ever detected struck the same dish in 2001 but was only reported in 2007. "A decade ago, we weren't really looking for them - and also our ability to handle the data and to search it in a reasonable time was significantly poorer," said Dr Keane, who now works for the Square Kilometre Array Organisation in Jodrell Bank, UK. "Whereas with this one, I was awoken by my phone going crazy a few seconds after it happened, saying: Evan, wake up! There was an FRB!"

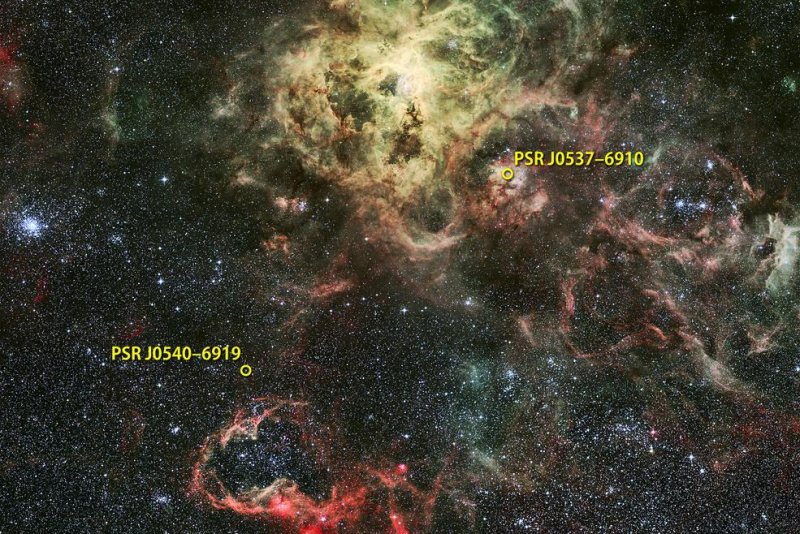

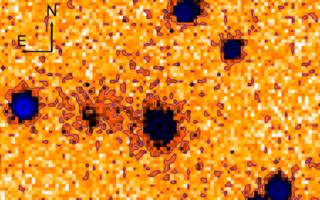

Two hours later, the six 22m dishes of the Australian Telescope Compact Array, a 400km drive from Parkes, were already homing in on the culpable corner of the sky. They caught an afterglow of the flash, which took six days to fade. It was much fainter than the burst itself but allowed the team to zoom in on the source of the burst with 1,000 times more precision than ever before. Knowing exactly where to look, they next went hunting in optical light using the Subaru Telescope in Hawaii, run by the National Astronomical Observatory of Japan. "Right where the Compact Array tells us there should be something, there is a galaxy," Dr Keane said. Close examination of the Subaru data showed the galaxy to be elliptical - an off-spherical blob of stars that is well past its prime, in galactic terms.

Cosmic weigh-in