R

rdean

Guest

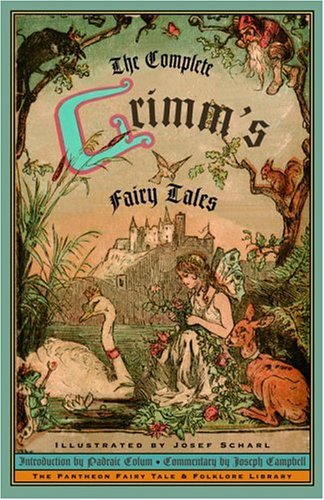

Well, there may be no evidence supporting the Grand Canyon being carved from Noah's Flood or Samson weakened merely from having his locks shorn, but those children's fables are certainly entertaining and they could make great Disney movies.