Agnapostate

Rookie

- Banned

- #1

I've recently completed reading Robin Hahnel's Panic Rules, and one of his appendices contains a simple but sound model indicating that free trade necessarily increases global inequality and deliver's the lion's share of efficiency gains to wealthier nations, as opposed to fair trade, which can eliminate both income inequality and inefficiency. Such insight is especially welcome when advocates of trade liberalization often resort to (mis)quoting Smith and Ricardo and babbling on about comparative advantage.

Hahnel's Models of International Trade

First, suppose that there are two varieties of countries, some in the "North" and some in the "South." We also assume that the international trade markets between Northern and Southern countries are perfectly competitive. (A concession to free market theory.) All countries have 1,000 citizens who must consume one unit of corn annually. There are two methods of corn production. One uses pure labor and the other uses a combination of labor and machines. There is one method of machine construction that requires both labor and machines. These are the technologies:

5 units of labor + 0 machines yields 10 units of corn

2 units of labor + 1 machine yields 10 units of corn

1 unit of labor + 2 machines yields 10 machines

Now, machines function for one year and must be replaced annually. Since machines are created from other machines, a certain number must be placed aside and utilized for the purpose of machine production rather than corn production, which will obviously result in greater long-term efficiency. Northern countries begin with 200 machines, whereas Southern countries begin with only 50 machines.

We will examine three models, a model in which Northern and Southern countries are not permitted to trade with each other, called the autarkic model, and two models in which trade is permitted but to different extents, the free trade and fair trade models. Recall that equality is measured through labor expenditures, as greater labor expenditures function as greater impositions on each respective population.

The Autarkic Model

Due to Northern countries' high surplus of machines, it is clear that making corn through the use of machines and labor will be far more productive than corn production through the sole use of labor. Corn production through the sole use of labor is entirely unnecessary in a Northern country, as a result of their machine supply. Let X(1) be the number of times that corn is produced through the sole use of labor, X(2) be the number of times corn is produced through a combination of machines and labor, and X(3) the number of times machines are produced using other machines. The most efficient production plan for a Northern country would be the following.

A Northern Country's Optimal Production Plan Under Autarky

X(1) = 0 using M(1) = 0 and L(1) = 0 to get 0 C

X(2) = 100 using M(2) = 100 and L(2) = 200 to get 1,000 C

X(3) = 12.5 using M(3) = 25 and L(3) = 12.5 to get 125 M

Such a plan necessitates the following in terms of machinery:

M(1) + M(2) + M(3) = 0 + 100 + 25 = 125 machines

This would replace the 125 machines used in the optimal production plan.

This is the amount of labor that would be necessary:

L(1) + L(2) + L(3) = 0 + 200 +12.5 = 212.5 units of labor

The 1,000 units of corn would thus be acquired. Now, this plan minimizes labor expenditures, but it only uses 125 of the 200 machines available for production purposes. And if trade is prohibited, and this is the most efficient manner of corn production, efficiency cannot be maximized inasmuch as 75 machines lie dormant.

Now, as for Southern countries, their 50 machines are not sufficient to produce 1,000 bushels of corn, especially considering that machines must be replaced. Since they must replace machines, the maximum amount of corn production through machine use must be X(2) = 40, and machine production must be X(3) = 5. But this yields only 400 bushels of corn, a 60% shortage. Hence, Southern countries must also resort to the less efficient method of corn production through the use of pure labor, so X(1) = 60. This would result in this plan:

A Southern Country's Optimal Production Plan Under Autarky

X(1) = 60 using M(1) = 0 and L(1) = 300 to get 600 C

X(2) = 40 using M(2) = 40 and L(2) = 80 to get 400 C

X(3) = 5 using M(3) = 10 and L(3) = 5 to get 50 M

600 C + 400 C thus yields the necessary 1,000 bushels of corn for consumption, and uses this in machine-based production.

M(1) + M(2) + M(3) = 0 + 40 + 10 = 50 machines

Hence, all machines are replaced, and the minimum expenditure of labor involved is this:

L(1) + L(2) + L(3) = 200 + 80 +5 = 385 units of labor.

Again, labor expenditures are the inequalities that must be measured, since both Northern and Southern countries have the same levels of corn consumption. Now, the degree of global inequality as measured through labor expenditures must be defined as the ratio of the number of average work days in Southern countries divided by the ratio of the number of average work days in Northern countries. If Northerners and Southerners have equivalent average labor amounts, the ration will be 1, but the ration and according degree of inequality will rise through greater labor expenditures by Southern workers than Northern workers. Hence, since Southerners work an average of 0.385 units of labor, whereas Northerners work an average of 0.2125 units of labor, the degree of inequality is measured as 0.385/0.2125 = 1.81. Now, the cause of this inequality is clearly different initial access to machine technology. But there is no method of rectifying this inequality since Northern and Southern countries are not permitted to trade with each other.

The Free Trade Model

The free trade model involves opening international trade for exchange of corn and machines and permitting trade conditions to be determined by the law of supply and demand in the international marketplace.

Machines are desired because they allow countries to produce corn more efficiently and easily. Hence, corn is the ultimate goal, and machines function as means to that end, which means that the number of corn bushels anyone would be willing to trade for machines can be calculated thusly: Assume that 17 units of labor existed. Without machines, only labor could be utilized in the process of corn production, which would mean that 34 C could be produced with 17 L. If, however, 10 machines were available, they could be utilized as a more efficient method of corn production, although the ten machines would obviously have to be replaced. 1 unit of labor and two machines is sufficient for this purpose. 16 units of labor and 8 machines are left to produce corn through the machine technology. 16 L and 8 M will produce 80 bushels of corn. Hence, if machines are available, this permits production of 80 - 34 = 46 more units of corn than pure labor, which amounts to 46/10 = 4.6 more units of corn per machine than would have been possible through pure labor.

Now, paying more than 4.6 units of corn for a machine is obviously inadvisable, since any country that did so would end up with less corn than its labor expenditures were worth. However, if machine prices were below 4.6 units of corn, countries would purchase them indefinitely since they would expend less labor per unit of corn by doing so. Hence, the equilibrium price of a machine, P(M), is 4.6 units of corn, and left to pure market forces, machines would sell for 4.6 units of corn. Now, let us examine the process of Northern and Southern countries' optimal production and trade plans under this scheme.

A Northern Country's Optimal Production Plan Under Free Trade

X(1) = 0 using M(1) = 0 and L(1) = 0 to get 0 C

X(2) = 14.815 using M(2) = 14.815 and L(2) = 29.63 to get 148.15 C

X(3) = 25 using M(3) = 50 and L(3) = 25 to get 250 M

Now, each Northern country uses 29.63 + 25 = 54.63 units of labor, 14.815 + 50 = 64.815 machines, and produces 148.15 units of corn and 250 machines.

A Northern Country's Optimal Trade Plan Under Free Trade

Export 250 - 64.815 = 185.185 M

Import 1,000 - 148.15 = 851.85 C

Now, since 185.185(4.6) = 851.85, each Northern country will have almost precisely enough machines to export in order to import a sufficient corn supply.*

Each Southern country can obtain 1,000 bushels of corn most efficiently with this production/trade scheme.

A Southern Country's Optimal Production Plan Under Free Trade

X(1) = 0 using M(1) = 0 and L(1) = 0 to get 0 C

X(2) = 185.185 using M(2) = 185.185 and L(2) = 370.37 to get 1851.85 C

X(3) = 0 using M(3) = 0 and L(3) = 25 to get 250 M

Now, each Southern country uses 370.37 units of labor, 185.185 machines, and produces 1851.85 units of corn.

A Southern Country's Optimal Trade Plan Under Free Trade

Export 1851.85 - 1,000 = 851.85 C

Import 185.185 M

Now, considering that 851.85/4.6 = 185.185, each Southern country will have almost precisely enough corn to export in order to import a sufficient machine supply, as with the Northern countries with the relevant goods reversed.

Here comes the clincher: Labor expenditures in terms of average work time are 0.37037 in Southern countries, while they are 0.05463 in Northern countries. Hence, the degree of global inequality in terms of labor expenditures have risen from 1.81 under autarky to 0.37037/0.05463 = 6.78 under free trade. The reason for this is that the vast majority of efficiency gains under the free trade model are distributed to Northern countries rather than Southern countries.

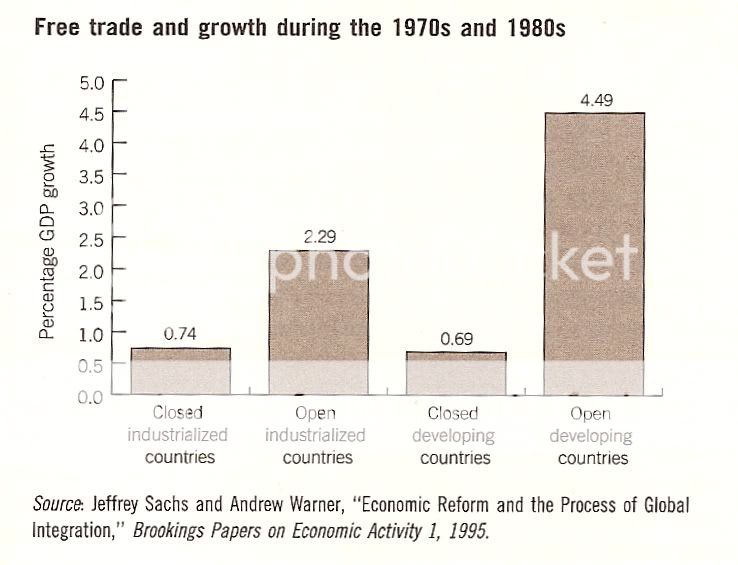

Increasing inequality is consistent with relevant research on the topic, such as Gini coefficient measurements of per capita income differences between countries. For instance, I have previously mentioned Walter Park and David Brat's research in A Global Kuznets Curve, which indicated that Gini coefficient measurements of GDP per capita increased during periods of neoliberal expansion.

Now, returning to the theoretical models, we have seen that under autarky, Northerners expend 212.5 units of labor, whereas Southerners expend 385 units of labor, which results in a total of 597.5 units of labor expended for the purpose of producing 2,000 units of corn. Under the free trade scheme, only 54.63 units of labor are expended in the North, while a lion's share of 370.73 units of labor are expended in the South, which brings a total of 425 units of labor to produce 2,000 units of corn. Recalling that all machines were replaced, free trade did indeed produce an efficiency gain of 597.5 - 425 = 172.5 units of labor saved in every Northern/Southern trade alliance. But Northern countries received 157.87 units of saved labor, reducing their work time from 212.5 to 54.63, whereas more unfortunate Southern countries only received 14.63 units of saved labor, which only reduced their average work time from 385 to 370.37.

Moreover, following the principle of charity, we gave the international free market every benefit of the doubt, by assuming that they reached their equilibrium price, for instance, by assuming that they were competitive, and by not assuming that the North held some monopolistic advantage, assumptions that would probably be too generous to the free market in the real world.

Clearly, the free market scheme suffers from some problems in that it imposes deleterious labor expenditures and conditions on the "lesser" countries, while efficiency gains are primarily enjoyed by the "greater" countries.

The Fair Trade Model

A solution is found through permitting Northern countries to trade machines to Southern countries in return for 0.5882 units of corn per machine, which has the effect of eliminating efficiency in the world economy, not negatively impacting Northern countries, and offering considerable benefit to Southern countries, whose labor expenditures would not be greater than those of Northern countries.

Since our terms of trade are P(M)/P(C) = 0.5882, this is the optimal production/trade scheme for Northern countries.

A Northern Country's Optimal Production Plan Under Free Trade

X(1) = 0 using M(1) = 0 and L(1) = 0 to get 0 C

X(2) = 93.75 using M(2) = 93.75 and L(2) = 187.5 to get 937.5 C

X(3) = 25 using M(3) = 50 and L(3) = 25 to get 250 M

Thus, each Northern country uses 187.5 + 25 = 212.5 units of labor, 93.75 + 50 = 143.75 machines, and produces 937.5 units of corn and 250 machines.

A Northern Country's Optimal Trade Plan Under Free Trade

Export 250 - 143.75 = 106.25 M

Import 1,000 - 937.5 = 62.5 C

Now, since 106.25(0.5882) = 62.5, each Northern country will have almost precisely enough machines to export in order to import a sufficient corn supply.

Continuing to use the formula P(M)/P(C) = 0.5882, a Southern country can maximize efficiency using this production plan.

A Southern Country's Optimal Production Plan Under Fair Trade

X(1) = 0 using M(1) = 0 and L(1) = 0 to get 0 C

X(2) = 106.25 using M(2) = 106.25 and L(2) = 212.5 to get 1062.5 C

X(3) = 0 using M(3) = 0 and L(3) = 0 to get 0 M

Each Southern country will use 212.5 units of labor, 106.25 machines, and will produce 1062.5 units of corn.

This is the most efficient trade scheme under fair trade.

A Southern Country's Optimal Trade Plan Under Fair Trade

Export 1062.5 - 1,000 = 62.5 C

Import 106.25 M

Naturally, as 62.5/(0.5882) = 106.25, each Southern country will have almost precisely enough corn to export in order to import a sufficient machine supply.

Fair trade has also permitted Southern countries to efficiently use the 75 additional machines that would have otherwise been dormant and unused in the North in an autarkic scheme. The same global efficiency gain is made as under free trade, 597.5 - 425 = 172.5 units of labor. But 100% of the efficiency gain is granted to the Southern countries, which reduces their labor expenditures from an average work time of 385 to 212.5, while not leaving the Northern countries any worse off than they were under autarky, as they also have an average work time of 212.5, reducing the ratio of global inequality from 1.81 under autarky and 6.78 under free trade to 1 under fair trade, eliminating inequality.

Hence, we find that the fair trade model is superior to either the autarkic or free trade models, since it has the effect of improving efficiency levels while not imposing negative social opportunity costs on countries in the same manner that the free trade model would.

There is obvious value in delivering greater efficiency gains to those in greatest need of it in the way of marginal utility. Northern countries with a large surplus in efficiency gains can do little with them in the way of necessities, and thus divert their additional assets to commodities, which provide far less utility than do necessities. Hence, if necessities are given to Southern countries before commodities are to Northern countries, this would be in line with acknowledging the diminishing rate of marginal utility that rising surpluses bring to the wealthy.

As Hahnel notes, the model can be used to calculate the effects of technical changes on global efficiency and international inequality, and leads one to the conclusion that one reason for the increase of global inequality is because technical change occurs more rapidly in capital-intensive sectors than labor-intensive sectors.

Hahnel's Models of International Trade

First, suppose that there are two varieties of countries, some in the "North" and some in the "South." We also assume that the international trade markets between Northern and Southern countries are perfectly competitive. (A concession to free market theory.) All countries have 1,000 citizens who must consume one unit of corn annually. There are two methods of corn production. One uses pure labor and the other uses a combination of labor and machines. There is one method of machine construction that requires both labor and machines. These are the technologies:

5 units of labor + 0 machines yields 10 units of corn

2 units of labor + 1 machine yields 10 units of corn

1 unit of labor + 2 machines yields 10 machines

Now, machines function for one year and must be replaced annually. Since machines are created from other machines, a certain number must be placed aside and utilized for the purpose of machine production rather than corn production, which will obviously result in greater long-term efficiency. Northern countries begin with 200 machines, whereas Southern countries begin with only 50 machines.

We will examine three models, a model in which Northern and Southern countries are not permitted to trade with each other, called the autarkic model, and two models in which trade is permitted but to different extents, the free trade and fair trade models. Recall that equality is measured through labor expenditures, as greater labor expenditures function as greater impositions on each respective population.

The Autarkic Model

Due to Northern countries' high surplus of machines, it is clear that making corn through the use of machines and labor will be far more productive than corn production through the sole use of labor. Corn production through the sole use of labor is entirely unnecessary in a Northern country, as a result of their machine supply. Let X(1) be the number of times that corn is produced through the sole use of labor, X(2) be the number of times corn is produced through a combination of machines and labor, and X(3) the number of times machines are produced using other machines. The most efficient production plan for a Northern country would be the following.

A Northern Country's Optimal Production Plan Under Autarky

X(1) = 0 using M(1) = 0 and L(1) = 0 to get 0 C

X(2) = 100 using M(2) = 100 and L(2) = 200 to get 1,000 C

X(3) = 12.5 using M(3) = 25 and L(3) = 12.5 to get 125 M

Such a plan necessitates the following in terms of machinery:

M(1) + M(2) + M(3) = 0 + 100 + 25 = 125 machines

This would replace the 125 machines used in the optimal production plan.

This is the amount of labor that would be necessary:

L(1) + L(2) + L(3) = 0 + 200 +12.5 = 212.5 units of labor

The 1,000 units of corn would thus be acquired. Now, this plan minimizes labor expenditures, but it only uses 125 of the 200 machines available for production purposes. And if trade is prohibited, and this is the most efficient manner of corn production, efficiency cannot be maximized inasmuch as 75 machines lie dormant.

Now, as for Southern countries, their 50 machines are not sufficient to produce 1,000 bushels of corn, especially considering that machines must be replaced. Since they must replace machines, the maximum amount of corn production through machine use must be X(2) = 40, and machine production must be X(3) = 5. But this yields only 400 bushels of corn, a 60% shortage. Hence, Southern countries must also resort to the less efficient method of corn production through the use of pure labor, so X(1) = 60. This would result in this plan:

A Southern Country's Optimal Production Plan Under Autarky

X(1) = 60 using M(1) = 0 and L(1) = 300 to get 600 C

X(2) = 40 using M(2) = 40 and L(2) = 80 to get 400 C

X(3) = 5 using M(3) = 10 and L(3) = 5 to get 50 M

600 C + 400 C thus yields the necessary 1,000 bushels of corn for consumption, and uses this in machine-based production.

M(1) + M(2) + M(3) = 0 + 40 + 10 = 50 machines

Hence, all machines are replaced, and the minimum expenditure of labor involved is this:

L(1) + L(2) + L(3) = 200 + 80 +5 = 385 units of labor.

Again, labor expenditures are the inequalities that must be measured, since both Northern and Southern countries have the same levels of corn consumption. Now, the degree of global inequality as measured through labor expenditures must be defined as the ratio of the number of average work days in Southern countries divided by the ratio of the number of average work days in Northern countries. If Northerners and Southerners have equivalent average labor amounts, the ration will be 1, but the ration and according degree of inequality will rise through greater labor expenditures by Southern workers than Northern workers. Hence, since Southerners work an average of 0.385 units of labor, whereas Northerners work an average of 0.2125 units of labor, the degree of inequality is measured as 0.385/0.2125 = 1.81. Now, the cause of this inequality is clearly different initial access to machine technology. But there is no method of rectifying this inequality since Northern and Southern countries are not permitted to trade with each other.

The Free Trade Model

The free trade model involves opening international trade for exchange of corn and machines and permitting trade conditions to be determined by the law of supply and demand in the international marketplace.

Machines are desired because they allow countries to produce corn more efficiently and easily. Hence, corn is the ultimate goal, and machines function as means to that end, which means that the number of corn bushels anyone would be willing to trade for machines can be calculated thusly: Assume that 17 units of labor existed. Without machines, only labor could be utilized in the process of corn production, which would mean that 34 C could be produced with 17 L. If, however, 10 machines were available, they could be utilized as a more efficient method of corn production, although the ten machines would obviously have to be replaced. 1 unit of labor and two machines is sufficient for this purpose. 16 units of labor and 8 machines are left to produce corn through the machine technology. 16 L and 8 M will produce 80 bushels of corn. Hence, if machines are available, this permits production of 80 - 34 = 46 more units of corn than pure labor, which amounts to 46/10 = 4.6 more units of corn per machine than would have been possible through pure labor.

Now, paying more than 4.6 units of corn for a machine is obviously inadvisable, since any country that did so would end up with less corn than its labor expenditures were worth. However, if machine prices were below 4.6 units of corn, countries would purchase them indefinitely since they would expend less labor per unit of corn by doing so. Hence, the equilibrium price of a machine, P(M), is 4.6 units of corn, and left to pure market forces, machines would sell for 4.6 units of corn. Now, let us examine the process of Northern and Southern countries' optimal production and trade plans under this scheme.

A Northern Country's Optimal Production Plan Under Free Trade

X(1) = 0 using M(1) = 0 and L(1) = 0 to get 0 C

X(2) = 14.815 using M(2) = 14.815 and L(2) = 29.63 to get 148.15 C

X(3) = 25 using M(3) = 50 and L(3) = 25 to get 250 M

Now, each Northern country uses 29.63 + 25 = 54.63 units of labor, 14.815 + 50 = 64.815 machines, and produces 148.15 units of corn and 250 machines.

A Northern Country's Optimal Trade Plan Under Free Trade

Export 250 - 64.815 = 185.185 M

Import 1,000 - 148.15 = 851.85 C

Now, since 185.185(4.6) = 851.85, each Northern country will have almost precisely enough machines to export in order to import a sufficient corn supply.*

Each Southern country can obtain 1,000 bushels of corn most efficiently with this production/trade scheme.

A Southern Country's Optimal Production Plan Under Free Trade

X(1) = 0 using M(1) = 0 and L(1) = 0 to get 0 C

X(2) = 185.185 using M(2) = 185.185 and L(2) = 370.37 to get 1851.85 C

X(3) = 0 using M(3) = 0 and L(3) = 25 to get 250 M

Now, each Southern country uses 370.37 units of labor, 185.185 machines, and produces 1851.85 units of corn.

A Southern Country's Optimal Trade Plan Under Free Trade

Export 1851.85 - 1,000 = 851.85 C

Import 185.185 M

Now, considering that 851.85/4.6 = 185.185, each Southern country will have almost precisely enough corn to export in order to import a sufficient machine supply, as with the Northern countries with the relevant goods reversed.

Here comes the clincher: Labor expenditures in terms of average work time are 0.37037 in Southern countries, while they are 0.05463 in Northern countries. Hence, the degree of global inequality in terms of labor expenditures have risen from 1.81 under autarky to 0.37037/0.05463 = 6.78 under free trade. The reason for this is that the vast majority of efficiency gains under the free trade model are distributed to Northern countries rather than Southern countries.

Increasing inequality is consistent with relevant research on the topic, such as Gini coefficient measurements of per capita income differences between countries. For instance, I have previously mentioned Walter Park and David Brat's research in A Global Kuznets Curve, which indicated that Gini coefficient measurements of GDP per capita increased during periods of neoliberal expansion.

This paper studies the inequality of nations, treating the country as the unit of analysis. First, measures of inequality are computed for 1960 to 1988. The international distribution of income has become more unequal over time. Secondly, the contribution of R&D investments and spillovers to global inequality is studied. Cross-country differences in R&D significantly account for the changes in the global distribution of income. National R&D investments have both a divergence and a convergence effect and, on net, the empirical results indicate that world R&D has a convergence effect. Controlling for R&D, the paper finds an inverted-U relationship between global inequality and global development.

Now, returning to the theoretical models, we have seen that under autarky, Northerners expend 212.5 units of labor, whereas Southerners expend 385 units of labor, which results in a total of 597.5 units of labor expended for the purpose of producing 2,000 units of corn. Under the free trade scheme, only 54.63 units of labor are expended in the North, while a lion's share of 370.73 units of labor are expended in the South, which brings a total of 425 units of labor to produce 2,000 units of corn. Recalling that all machines were replaced, free trade did indeed produce an efficiency gain of 597.5 - 425 = 172.5 units of labor saved in every Northern/Southern trade alliance. But Northern countries received 157.87 units of saved labor, reducing their work time from 212.5 to 54.63, whereas more unfortunate Southern countries only received 14.63 units of saved labor, which only reduced their average work time from 385 to 370.37.

Moreover, following the principle of charity, we gave the international free market every benefit of the doubt, by assuming that they reached their equilibrium price, for instance, by assuming that they were competitive, and by not assuming that the North held some monopolistic advantage, assumptions that would probably be too generous to the free market in the real world.

Clearly, the free market scheme suffers from some problems in that it imposes deleterious labor expenditures and conditions on the "lesser" countries, while efficiency gains are primarily enjoyed by the "greater" countries.

The Fair Trade Model

A solution is found through permitting Northern countries to trade machines to Southern countries in return for 0.5882 units of corn per machine, which has the effect of eliminating efficiency in the world economy, not negatively impacting Northern countries, and offering considerable benefit to Southern countries, whose labor expenditures would not be greater than those of Northern countries.

Since our terms of trade are P(M)/P(C) = 0.5882, this is the optimal production/trade scheme for Northern countries.

A Northern Country's Optimal Production Plan Under Free Trade

X(1) = 0 using M(1) = 0 and L(1) = 0 to get 0 C

X(2) = 93.75 using M(2) = 93.75 and L(2) = 187.5 to get 937.5 C

X(3) = 25 using M(3) = 50 and L(3) = 25 to get 250 M

Thus, each Northern country uses 187.5 + 25 = 212.5 units of labor, 93.75 + 50 = 143.75 machines, and produces 937.5 units of corn and 250 machines.

A Northern Country's Optimal Trade Plan Under Free Trade

Export 250 - 143.75 = 106.25 M

Import 1,000 - 937.5 = 62.5 C

Now, since 106.25(0.5882) = 62.5, each Northern country will have almost precisely enough machines to export in order to import a sufficient corn supply.

Continuing to use the formula P(M)/P(C) = 0.5882, a Southern country can maximize efficiency using this production plan.

A Southern Country's Optimal Production Plan Under Fair Trade

X(1) = 0 using M(1) = 0 and L(1) = 0 to get 0 C

X(2) = 106.25 using M(2) = 106.25 and L(2) = 212.5 to get 1062.5 C

X(3) = 0 using M(3) = 0 and L(3) = 0 to get 0 M

Each Southern country will use 212.5 units of labor, 106.25 machines, and will produce 1062.5 units of corn.

This is the most efficient trade scheme under fair trade.

A Southern Country's Optimal Trade Plan Under Fair Trade

Export 1062.5 - 1,000 = 62.5 C

Import 106.25 M

Naturally, as 62.5/(0.5882) = 106.25, each Southern country will have almost precisely enough corn to export in order to import a sufficient machine supply.

Fair trade has also permitted Southern countries to efficiently use the 75 additional machines that would have otherwise been dormant and unused in the North in an autarkic scheme. The same global efficiency gain is made as under free trade, 597.5 - 425 = 172.5 units of labor. But 100% of the efficiency gain is granted to the Southern countries, which reduces their labor expenditures from an average work time of 385 to 212.5, while not leaving the Northern countries any worse off than they were under autarky, as they also have an average work time of 212.5, reducing the ratio of global inequality from 1.81 under autarky and 6.78 under free trade to 1 under fair trade, eliminating inequality.

Hence, we find that the fair trade model is superior to either the autarkic or free trade models, since it has the effect of improving efficiency levels while not imposing negative social opportunity costs on countries in the same manner that the free trade model would.

There is obvious value in delivering greater efficiency gains to those in greatest need of it in the way of marginal utility. Northern countries with a large surplus in efficiency gains can do little with them in the way of necessities, and thus divert their additional assets to commodities, which provide far less utility than do necessities. Hence, if necessities are given to Southern countries before commodities are to Northern countries, this would be in line with acknowledging the diminishing rate of marginal utility that rising surpluses bring to the wealthy.

As Hahnel notes, the model can be used to calculate the effects of technical changes on global efficiency and international inequality, and leads one to the conclusion that one reason for the increase of global inequality is because technical change occurs more rapidly in capital-intensive sectors than labor-intensive sectors.