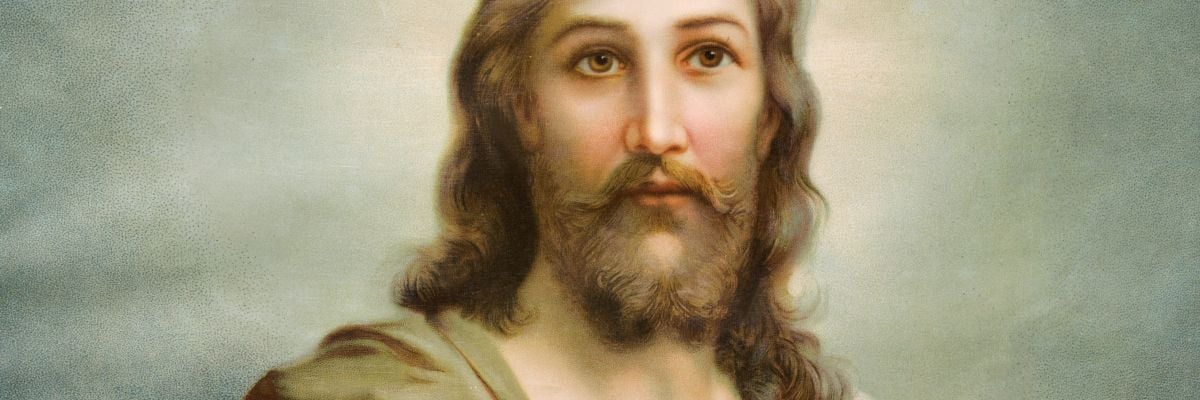

The central tenets of Christianity are that Jesus was God in human form, died on the Cross, was physically resurrected and then ascended to Heaven. From a logical viewpoint, I have the following questions:

1. If Jesus was a human being, he would have had 64 chromosomes, 32 from his mother and 32 from his father. The only exception would be if he was cloned from his mother. In that case wouldn't he have been female?

2. After Jesus died on the Cross, was he physically resurrected as a human being? If so, how did he ascend to Heaven? Is Heaven a physical place? Do other human beings live there as well? If not, why not?

1. If Jesus was a human being, he would have had 64 chromosomes, 32 from his mother and 32 from his father. The only exception would be if he was cloned from his mother. In that case wouldn't he have been female?

2. After Jesus died on the Cross, was he physically resurrected as a human being? If so, how did he ascend to Heaven? Is Heaven a physical place? Do other human beings live there as well? If not, why not?