Do you accept the concept that we all descended from a common ancestor? Whatever the actual mechanism.Which the fossil record does not support.

Darwin's understanding of inheritance was flawed and he built his theory on that flaw.

“It seems pretty clear that organic beings must be exposed during several generations to the new conditions of life to cause any appreciable amount of variation; and that when the organisation has once begun to vary, it generally continues to vary for many generations” (Darwin 1861, p. 7).

Navigation

Install the app

How to install the app on iOS

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature may not be available in some browsers.

More options

Style variation

You are using an out of date browser. It may not display this or other websites correctly.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

You should upgrade or use an alternative browser.

Paleontologist Explains What The Fossils Really Say

- Thread starter Viktor

- Start date

The creation geologist backs me up. All you have is evolutionist opinion, so no need for me to agree with your bullshit. You can't prove millions or so years as my radiocarbon dating disproved it.

Man, your assertions are just colossal bullshit lmao. I don't believe your scientists as evidence of humans and dinosaurs hurts evolution. All they have is papers biased atheist scientists wrote. That isn't evidence. Moreover, you have nothing to show millions of years while creationists have dino fossils with soft tissue and C14 remaining.

Creation geologist? What university offers that degree?

Colin norris

Platinum Member

- Apr 25, 2021

- 10,427

- 4,110

- 928

- Banned

- #123

Dr Gunther Bechly says Darwin was wrong

Bechly is the one who is wrong. That fact he said that proves evolution failed when installing intelligence into him and anyone who believes him.

I believe we come from common ancestors. Plural. I don't believe that evolution occurs in onesies and twosies. Because logic, statistics and the fossil record does not support that. Speciation occurs across the herd as an event. Such that there is a fairly rapid transition - i.e. one or two generations - from one species to another species with the original species dying out because that is what the fossil record shows with respect to speciation.Do you accept the concept that we all descended from a common ancestor? Whatever the actual mechanism.

I do not believe that....

"...organic beings must be exposed during several generations to the new conditions of life to cause any appreciable amount of variation; and that when the organisation has once begun to vary, it generally continues to vary for many generations” (Darwin 1861, p. 7)...

And if Darwin had known about genetics and genetic mutations, I don't believe he would have believed what he wrote in his book either.

"...organic beings must be exposed during several generations to the new conditions of life to cause any appreciable amount of variation; and that when the organisation has once begun to vary, it generally continues to vary for many generations” (Darwin 1861, p. 7)...

And if Darwin had known about genetics and genetic mutations, I don't believe he would have believed what he wrote in his book either.

The changes are recorded in the genome of every bird. There are many types of feathers, only one or two of which enables flight. Most birds preserve this multitude of types since the feathers that don't support flight are not needed on the body.So how long did this "slight" change from scales to feathers occur and where is the fossil record of that change to show the gradual changes from scales to feathers.

I think that is an absurdly short amount of time. We're talking about geology where a thousand years is instantaneous.I believe we come from common ancestors. Plural. I don't believe that evolution occurs in onesies and twosies. Because logic, statistics and the fossil record does not support that. Speciation occurs across the herd as an event. Such that there is a fairly rapid transition - i.e. one or two generations - from one species to another species with the original species dying out because that is what the fossil record shows with respect to speciation.

How does this show that these organic beings were exposed during several generations to new conditions of life before any appreciable amount of variation occurred and that once it began to vary, it continued to vary for many generations?The changes are recorded in the genome of every bird. There are many types of feathers, only one or two of which enables flight. Most birds preserve this multitude of types since the feathers that don't support flight are not needed on the body.

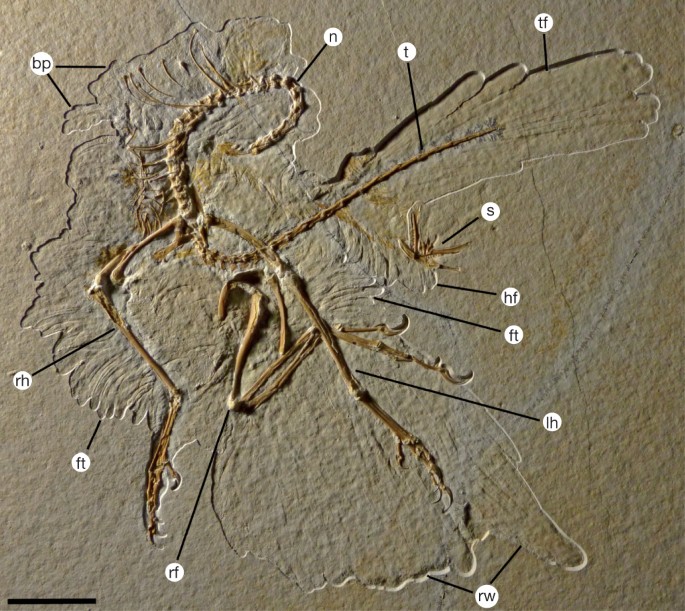

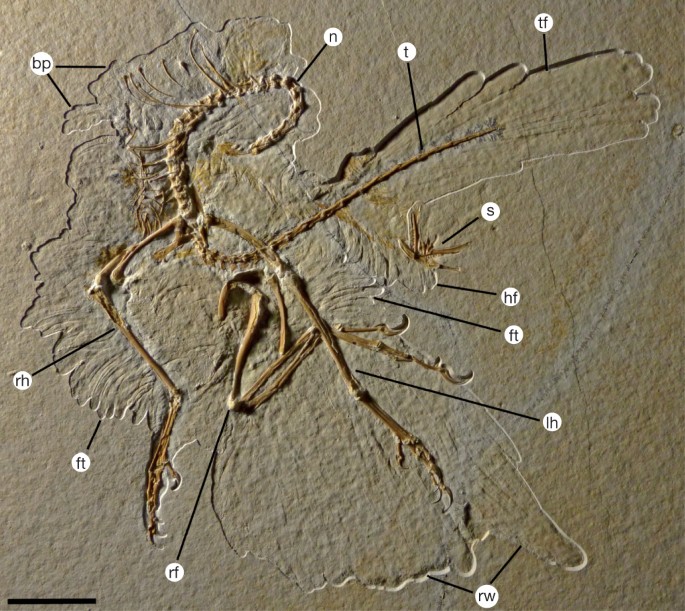

Discoveries of bird-like theropod dinosaurs and basal avialans in recent decades have helped to put the iconic ‘Urvogel’ Archaeopteryx1 into context2,3,4,5,6 and have yielded important new data on the origin and early evolution of feathers7. However, the biological context under which pennaceous feathers evolved is still debated. Here we describe a new specimen of Archaeopteryx with extensive feather preservation, not only on the wings and tail, but also on the body and legs. The new specimen shows that the entire body was covered in pennaceous feathers, and that the hindlimbs had long, symmetrical feathers along the tibiotarsus but short feathers on the tarsometatarsus. Furthermore, the wing plumage demonstrates that several recent interpretations8,9 are problematic. An analysis of the phylogenetic distribution of pennaceous feathers on the tail, hindlimb and arms of advanced maniraptorans and basal avialans strongly indicates that these structures evolved in a functional context other than flight, most probably in relation to display, as suggested by some previous studies10,11,12. Pennaceous feathers thus represented an exaptation and were later, in several lineages and following different patterns, recruited for aerodynamic functions. This indicates that the origin of flight in avialans was more complex than previously thought and might have involved several convergent achievements of aerial abilities.

Why? Do you understand how genes work?I think that is an absurdly short amount of time. We're talking about geology where a thousand years is instantaneous.

We aren't talking about geology. We are talking about biology.

I shows there are many small changes in the feather to bring it to the flight feathers we see today. Feathers didn't suddenly appear in the fossil record.How does this show that these organic beings were exposed during several generations to new conditions of life before any appreciable amount of variation occurred and that once it began to vary, it continued to vary for many generations?

I have a vague notion of genetics but I do know that when you talk fossils you are talking about geology.Why? Do you understand how genes work?

We aren't talking about geology. We are talking about biology.

james bond

Gold Member

- Oct 17, 2015

- 13,407

- 1,805

- 170

As usual, what the evo believers and atheists have are ad hominem attacks. It shows that you lost the argument. You have nothing to show millions of years that you claimed. Thus, now you want the limestone evidence again. It's on top of Mt. Everest. Go hike up there lol.Once again, that is a contradiction.

And when I talk about geology, I talk about geology. You see, geology does not give a damn about evolution, or the Bible, or anything else. It only cares about the planet, the rocks, and how the two of them developed. You are trying to mash them together, and that is a fail. Like trying to compare ERA stats in baseball, and saying a player is better or worse than a football quarterback because of their yards passed stats.

This is why you keep failing, because I am actually talking very little about evolution itself. I am discussing geology, and slightly into anthropology and paleontology. I am dismissing your claims based on the science of that alone, and not even going into biology, or actual evolution.

But please tell me, where are all these lime volcanos? Or these massive "lime floods", because there is no evidence of either of those events happening ever.

That is the difference. I use actual hard observation and science, you are believing fairy stories that are completely made up and have no basis in reality.

And you reject my assertations as "bullshit", yet ignore the fact once again that your reference lied to you. When faced with the fact they lied, you still believe them and what they say, and reject actual hard evidence that you were lied to.

As I said, take this claim down to the religion area. It does not belong here.

OTOH, I showed dinosaurs are less than 50,000 years old as C14 is still remaining in their fossils.

What other fossils were in the dinosaur level that shows what animals lived with it? It means they lived together. There were squirrels, platypus, beavers, badgers, snakes, reptiles, frogs, fish, and more. Most surprising was they found birds with them -- parrots, penguins, owls, sandpipers, albatross, flamingos, loons, ducks, cormorants and avocets. That said, the evo paleontologists purposely disregarded them, i.e. they lied by omission. Thus, if a human fossil were ever to be found in the same level, then I think they would lie again. Your evo paleontologist make up their own findings to fit evolution. Obviously, if they contradicted the fairy tale of evolution, then they would be ostracized. How did this ever happen?

ETA: Listen, if I ever found out that my whole life was a lie, then that may set off a heart attack and that would be it. A life cut down before its time. However, I started to go by the Bible in 2012 and discovered science backs up the Bible. My story can't change while evolution's changes or is made to fit its main story line, i.e. there was no creation. What's weird is people ended up disbelieving God with no solid evidence. Nothing pops into existence by abiogeneis (disproved by Pasteur's swan neck experiment) nor an explanation of why. There is no evidence as the evidence disproves evolution lmao.

Last edited:

Have you seen the fossil sequence of small changes with your own eyes?I shows there are many small changes in the feather to bring it to the flight feathers we see today. Feathers didn't suddenly appear in the fossil record.

That is incorrect. Geology is the science that deals with the earth's physical structure and substance, its history, and the processes that act on it. Paleontology is the branch of science concerned with fossil animals and plants.I have a vague notion of genetics but I do know that when you talk fossils you are talking about geology.

Mushroom

Gold Member

Most birds preserve this multitude of types since the feathers that don't support flight are not needed on the body.

Since when do Emu's and Penguins fly?

False analysis, however the birds I mentioned have feathers for the same reason most late dinosaurs did. Temperature regulation.

Mushroom

Gold Member

Have you seen the fossil sequence of small changes with your own eyes?

Hell, just look at humans. We are still evolving even to this day.

Mushroom

Gold Member

So how long did this "slight" change from scales to feathers occur and where is the fossil record of that change to show the gradual changes from scales to feathers.

Here is the fascinating thing, the timeline keeps getting pushed back.

I am old enough to remember the shockwaves when some were first speculating that birds had evolved from dinosaurs, and that some dinosaurs had feathers. And each decade, paleontologists keep looking back more and more, and seeing that the evidence for feathers existed much earlier than they ever thought.

For over a century, it was believed that birds largely evolved after dinosaurs died out. But it was around 1976 that this belief started to change, and they realized that the earliest birds were dinosaurs. And that many of the ones we are most familiar with actually had feathers. Including at least some relatives of the T. Rex.

BackAgain

Neutronium Member & truth speaker #StopBrandon

If you want to know what the fossils say, ask Joe Brandon and Nancy Pelousy. They were there.

BackAgain

Neutronium Member & truth speaker #StopBrandon

My last comment got a downvote! Yeah. Yeah. I know. I mean, I was shocked, too! Especially since I can PROVE it!

Scientists have studied Joe Brandon’s ancient fossilized footprints for several years and concluded that even back then, he had a severe cognitive deficit.

Scientists have studied Joe Brandon’s ancient fossilized footprints for several years and concluded that even back then, he had a severe cognitive deficit.

Yes, sticking with feathers, you can see them get more complex over time.Have you seen the fossil sequence of small changes with your own eyes?

Similar threads

- Replies

- 12

- Views

- 182

- Replies

- 12

- Views

- 341

New Topics

-

Now here's something you don't see everyday....White people brawl!

- Started by 1srelluc

- Replies: 0

-

Canada announces new ‘Same Day Suicides’ as euthanasia numbers reach over 75K…

- Started by excalibur

- Replies: 0

-

-

Zone1 Record Number Of Bibles Sold In 2025 in the USA and the UK

- Started by SaxonJackson

- Replies: 4

-