Baron

Platinum Member

Hey, neocon morons, not you will babble how Russians have to deal with Ukrainian Nazi animals

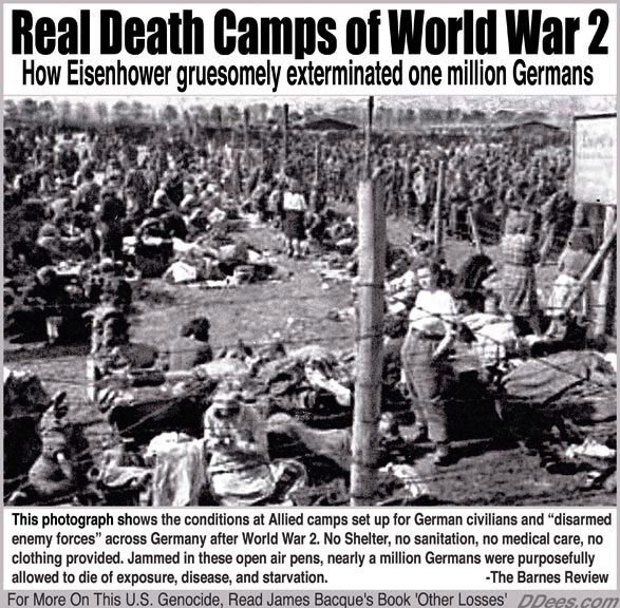

Call it callousness, call it reprisal, call it a policy of hostile neglect: a million Germans taken prisoner by Eisenhower’s armies died in captivity after the surrender.

In the spring of 1945, Adolph Hitler’s Third Reich was on the brink of collapse, ground between the Red Army, advancing westward towards Berlin, and the American, British, and Canadian armies, under the overall command of General Dwight Eisenhower, moving eastward over the Rhine. Since the D-Day landings in Normandy the previous June, the westward Allies had won back France and the Low Countries, and some Wehrmacht commanders were already trying to negotiate local surrenders. Other units, though, continued to obey Hitler’s orders to fight to the last man. Most systems, including transport, had broken down, and civilians in panic flight fromt he advancing Russians roamed at large.

“Hungry and frightened, lying in grain fields within fifty feet of us, awaiting the appropriate time to jump up with their hands in the air”; that’s how Captain H. F. McCullough of the 2nd Anti-Tank Regiment Division described the chaos of the German surrender at the end of the Second World War. In a day and a half, according to Field Marshall Bernard Montgomery, 500,000 Germans surrendered to his 21st Army Group in Northern Germany. Soon after V-E Day–May 8, 1945–the British-Canadian catch totalled more that 2 million. Virtually nothing about their treatment survives in the archives in Ottawa or London, but some skimpy evidence from the International Committee of the Red Cross, the armies concerned, and the prisoners themselves indicates that almost all continued in fair health. In any case, most were quickly released and sent home, or else transferred to the French to help in the post-war work of reconstruction. The French army had itself taken fewer than 300,000 prisoners.

Like the British and Canadians, the Americans suddenly faced astounding numbers of surrendering German troops: the final tally of prisoners taken by the U.S. army in Europe (excluding Italy and North Africa) was 5.25 million. But the Americans responded very differently.

Among the early U.S captives was one Corporal Helmut Liebich, who had been working in an anti-aircraft experimental group at Peenemunde on the Baltic. Liebich was captured by the Americans on April 17, near Gotha in Central Germany. Forty-two years later, he recalled vividly that there were no tents in the Gotha camp, just barbed wire fences around a field soon churned to mud. The prisoners received a small ration of food on the first day but it was then cut in half. In order to get it, they were forced to run a gauntlet. Hunched ocer, they ran between lines of American guards who hit them with sticks as they scurried towards their food. On April 27, they were transferred to the U.S. camp at Heidesheim farther wet, where there was no food at all for days, then very little. Exposed, starved, and thirsty, the men started to die. Liebich saw between ten and thirty bodies a day being dragged out of his section, B, which at first held around 5,200 men.. He saw one prisoner beat another to death to get his piece of bread. One night when it rained, Liebich saw the sides of the holes in which they were sheltered, dug in soft sandy earth, collapse on men who were too weak to struggle out. They smothered before anyone could get to them. Liebich sat down and wept. “I could hardly believe men could be so cruel to each other.”

Typhus broke out in Heidesheim about the beginning of May. Five days after V-E Day, on May 13, Liebich was transferred to another U.S. POW camp, at Bingen-Rudesheim in the Rhineland near Bad Kreuznach, where he was told that the prisoners numbered somewhere between 200,000 and 400,000, all without shelter, food, water, medicine, or sufficient space.

Soon he fell sick with dysentery and typhus. he was moved again, semiconscious and delirious, in an open-topped railway car with about sixty other prisoners: northwest down the Rhine, with a detour through Holland, where the Dutch stood on bridges to smash stones down on the heads of the prisoners. Sometimes the American guards fired warning shots near the Dutch to keep them off. After three nights, his fellow prisoners helped him stagger into the hug camp at Rheinberg, near the border with the Netherlands, again without shelter or food.

................

..................

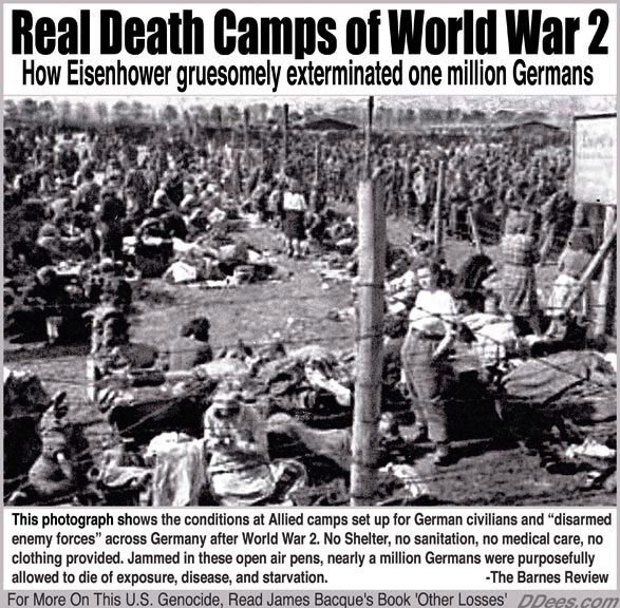

Call it callousness, call it reprisal, call it a policy of hostile neglect: a million Germans taken prisoner by Eisenhower’s armies died in captivity after the surrender.

In the spring of 1945, Adolph Hitler’s Third Reich was on the brink of collapse, ground between the Red Army, advancing westward towards Berlin, and the American, British, and Canadian armies, under the overall command of General Dwight Eisenhower, moving eastward over the Rhine. Since the D-Day landings in Normandy the previous June, the westward Allies had won back France and the Low Countries, and some Wehrmacht commanders were already trying to negotiate local surrenders. Other units, though, continued to obey Hitler’s orders to fight to the last man. Most systems, including transport, had broken down, and civilians in panic flight fromt he advancing Russians roamed at large.

“Hungry and frightened, lying in grain fields within fifty feet of us, awaiting the appropriate time to jump up with their hands in the air”; that’s how Captain H. F. McCullough of the 2nd Anti-Tank Regiment Division described the chaos of the German surrender at the end of the Second World War. In a day and a half, according to Field Marshall Bernard Montgomery, 500,000 Germans surrendered to his 21st Army Group in Northern Germany. Soon after V-E Day–May 8, 1945–the British-Canadian catch totalled more that 2 million. Virtually nothing about their treatment survives in the archives in Ottawa or London, but some skimpy evidence from the International Committee of the Red Cross, the armies concerned, and the prisoners themselves indicates that almost all continued in fair health. In any case, most were quickly released and sent home, or else transferred to the French to help in the post-war work of reconstruction. The French army had itself taken fewer than 300,000 prisoners.

Like the British and Canadians, the Americans suddenly faced astounding numbers of surrendering German troops: the final tally of prisoners taken by the U.S. army in Europe (excluding Italy and North Africa) was 5.25 million. But the Americans responded very differently.

Among the early U.S captives was one Corporal Helmut Liebich, who had been working in an anti-aircraft experimental group at Peenemunde on the Baltic. Liebich was captured by the Americans on April 17, near Gotha in Central Germany. Forty-two years later, he recalled vividly that there were no tents in the Gotha camp, just barbed wire fences around a field soon churned to mud. The prisoners received a small ration of food on the first day but it was then cut in half. In order to get it, they were forced to run a gauntlet. Hunched ocer, they ran between lines of American guards who hit them with sticks as they scurried towards their food. On April 27, they were transferred to the U.S. camp at Heidesheim farther wet, where there was no food at all for days, then very little. Exposed, starved, and thirsty, the men started to die. Liebich saw between ten and thirty bodies a day being dragged out of his section, B, which at first held around 5,200 men.. He saw one prisoner beat another to death to get his piece of bread. One night when it rained, Liebich saw the sides of the holes in which they were sheltered, dug in soft sandy earth, collapse on men who were too weak to struggle out. They smothered before anyone could get to them. Liebich sat down and wept. “I could hardly believe men could be so cruel to each other.”

Typhus broke out in Heidesheim about the beginning of May. Five days after V-E Day, on May 13, Liebich was transferred to another U.S. POW camp, at Bingen-Rudesheim in the Rhineland near Bad Kreuznach, where he was told that the prisoners numbered somewhere between 200,000 and 400,000, all without shelter, food, water, medicine, or sufficient space.

Soon he fell sick with dysentery and typhus. he was moved again, semiconscious and delirious, in an open-topped railway car with about sixty other prisoners: northwest down the Rhine, with a detour through Holland, where the Dutch stood on bridges to smash stones down on the heads of the prisoners. Sometimes the American guards fired warning shots near the Dutch to keep them off. After three nights, his fellow prisoners helped him stagger into the hug camp at Rheinberg, near the border with the Netherlands, again without shelter or food.

................

..................