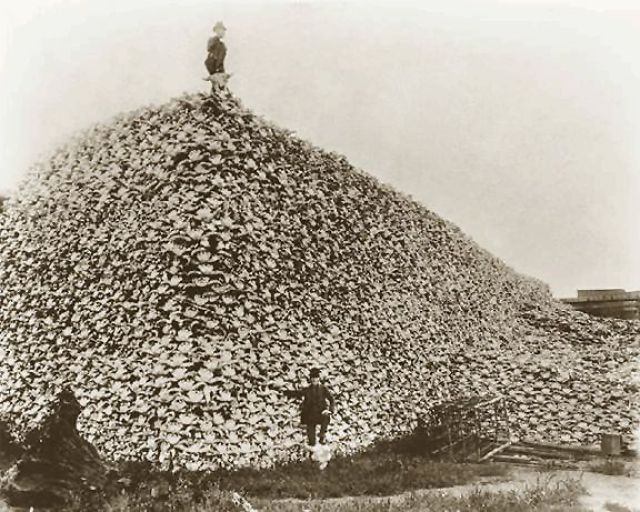

This is not Auschwitz. Not Buchenwald. Not Majdanek. This was OUR America ... Bones of slain Native Americans

Do you have a source or authentication for that picture?

This is taken from a common source of pictures and photographs.

Those that are lower are from special ones.

Do you have doubts that the bones of a hundred million make up such a mountain? Of course not. It would be a mountain of monstrous size and height ...

Photo Intelligence of the Native Americans' campsite

The moment of encirclement by the military of the settlement of Wounded Knee

The bodies of slaughtered Native Americans

Frozen corps of slaughtered Native Americans

U.S. Soldiers putting Lakota corpses in common grave

T

he Wounded Knee Massacre (also called the Battle of Wounded Knee) was a domestic massacre of several hundred Lakota Indians, mostly women and children, by soldiers of the United States Army. It occurred on December 29, 1890,[5] near Wounded Knee Creek (Lakota: Čhaŋkpé Ópi Wakpála) on the Lakota Pine Ridge Indian Reservation in the U.S. state of South Dakota, following a botched attempt to disarm the Lakota camp.

The previous day, a detachment of the U.S. 7th Cavalry Regiment commanded by Major Samuel M. Whitside intercepted Spotted Elk's band of Miniconjou Lakota and 38 Hunkpapa Lakota near Porcupine Butte and escorted them 5 miles (8.0 km) westward to Wounded Knee Creek, where they made camp. The remainder of the 7th Cavalry Regiment, led by Colonel James W. Forsyth, arrived and surrounded the encampment. The regiment was supported by a battery of four Hotchkiss mountain guns.[6]

On the morning of December 29, the U.S. Cavalry troops went into the camp to disarm the Lakota. One version of events claims that during the process of disarming the Lakota, a deaf tribesman named Black Coyote was reluctant to give up his rifle, claiming he had paid a lot for it. Simultaneously, an old man was performing a ritual called the Ghost Dance. Black Coyote's rifle went off at that point, and the U.S. army began shooting at the Native Americans. The Lakota warriors fought back, but many had already been stripped of their guns and disarmed.

By the time the massacre was over, between 250 and 300 men, women, and children of the Lakota had been killed and 51 were wounded (4 men and 47 women and children, some of whom died later); some estimates placed the number of dead at 300.

Twenty-five soldiers also died, and thirty-nine were wounded (six of the wounded later died).

Twenty soldiers were awarded the Medal of Honor.

In 2001, the National Congress of American Indians passed two resolutions condemning the military awards and called on the U.S. government to rescind them.

The Wounded Knee Battlefield, site of the massacre, has been designated a National Historic Landmark by the U.S. Department of the Interior.

In 1990, both houses of the U.S. Congress passed a resolution on the historical centennial formally expressing "deep regret" for the massacre.

The Christen killers

The Gnadenhutten Massacre, 1782. (Credit: Archive Photos/Getty Images)

In the South, the War of 1812 bled into the Mvskoke Creek War of 1813-1814, also known as the Red Stick War. An inter-tribal conflict among Creek Indian factions, the war also engaged U.S. militias, along with the British and Spanish, who backed the Indians to help keep Americans from encroaching on their interests. Early Creek victories inspired General

Andrew Jackson to retaliate with 2,500 men, mostly Tennessee militia, in early November 1814. To avenge the Creek-led massacre at Fort Mims, Jackson and his men slaughtered 186 Creeks at Tallushatchee. “We shot them like dogs!” said

Davy Crockett.

In desperation, Mvskoke Creek women killed their children so they would not see the soldiers butcher them. As one woman started to kill her baby, the famed Indian fighter, Andrew Jackson, grabbed the child from the mother. Later, he delivered the Indian baby to his wife Rachel, for both of them to raise as their own.

Jackson went on to win the Red Stick War in a decisive battle at Horseshoe Bend. The subsequent treaty required the Creek to cede more than 21 million acres of land to the United States.

“Trail of Tears.” And as whites pushed ever westward, the Indian-designated territory continued to shrink.

President Lincoln sent soldiers, who defeated the Dakota; and after a series of mass trials, more than 300 Dakota men were sentenced to death.

While Lincoln commuted most of the sentences, on the day after Christmas at Mankato, military officials hung 38 Dakotas at once—the largest mass execution in American history. More than 4,000 people gathered in the streets to watch, many bringing picnic baskets. The 38 were buried in a shallow grave along the Minnesota River, but physicians dug up most of the bodies to use as medical cadavers.

November 29, 1864, a former Methodist minister, John Chivington, led a surprise attack on peaceful Cheyennes and Arapahos on their reservation at Sand Creek in southeastern Colorado. His force consisted of 700 men, mainly volunteers in the First and Third Colorado Regiments. Plied with too much liquor the night before, Chivington and his men boasted that they were going to kill Indians. Once a missionary to Wyandot Indians in Kansas, Chivington declared, “Damn any man who sympathizes with Indians!…I have come to kill Indians, and believe it is right and honorable to use any means under God’s heavens to kill Indians.”

That fateful cold morning, Chivington led his men against 200 Cheyennes and Arapahos. Cheyenne Chief Black Kettle had tied an American flag to his lodge pole as he was instructed, to indicate his village was at peace. When Chivington ordered the attack, Black Kettle tied a white flag beneath the American flag, calling to his people that the soldiers would not kill them. As many as 160 were massacred, mostly women and children.

Custer’s Campaigns

At this time, a war hero from the Civil War emerged in the West.

George Armstrong Custer rode in front of his mostly Irish Seventh Cavalry to the Irish drinking tune, “Gary Owen.” Custer wanted fame, and killing Indians—especially peaceful ones who weren’t expecting to be attacked—represented opportunity.

General Philip Sheridan, Custer and his Seventh attacked the Cheyennes and their Arapaho allies on the western frontier of Indian Territory on November 29, 1868, near the Washita River. After slaughtering 103 warriors, plus women and children, Custer dispatched to Sheridan that “a great victory was won,” and described, “One, the Indians were asleep. Two, the women and children offered little resistance. Three, the Indians are bewildered by our change of policy.”

Custer later led the Seventh Cavalry on the northern Plains against the Lakota, Arapahos and Northern Cheyennes. He boasted, “The Seventh can handle anything it meets,” and “there are not enough Indians in the world to defeat the Seventh Cavalry.”

Expecting another great surprise victory, Custer attacked the largest gathering of warriors on the high plains on

June 25, 1876—near Montana’s Little Big Horn river. Custer’s death at the hands of Indians making their own last stand only intensified propaganda for military revenge to bring “peace” to the frontier.

Chief Sitting Bull was killed while being arrested, the U.S. Army’s Seventh Cavalry massacred 150 to 200 ghost dancers at

Wounded Knee, South Dakota.

For their mass murder of disarmed Lakota, President

Benjamin Harrison awarded about 20 soldiers the Medal of Honor.

Resilience

Three years after Wounded Knee, Professor Frederick Jackson Turner announced at a small gathering of historians in Chicago that the “frontier had closed,” with his famous thesis arguing for American exceptionalism. James Earle Fraser’s famed sculpture “End of the Trail,” which debuted in 1915 at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, exemplified the idea of a broken, vanishing race. Ironically, just over 100 years later, the resilient American Indian population has survived into the 21st century and swelled to more than 5 million people

A painting depicting the Trail of Tears, when Native Americans were forced by law to leave their homelands and move to designated territory in the west. (Credit: Al Moldvay/The Denver Post via Getty Images)

From 1830 to 1840, the U.S. army removed 60,000 Indians—Choctaw, Creek, Cherokee and others—from the East in exchange for new territory west of the Mississippi. Thousands died along the way of what became known as the

“Trail of Tears.” And as whites pushed ever westward, the Indian-designated territory continued to shrink.

President Lincoln sent soldiers, who defeated the Dakota; and after a series of mass trials, more than 300 Dakota men were sentenced to death.

While Lincoln commuted most of the sentences, on the day after Christmas at Mankato, military officials hung 38 Dakotas at once—the largest mass execution in American history. More than 4,000 people gathered in the streets to watch, many bringing picnic baskets. The 38 were buried in a shallow grave along the Minnesota River, but physicians dug up most of the bodies to use as medical cadavers.

November 29, 1864, a former Methodist minister, John Chivington, led a surprise attack on peaceful Cheyennes and Arapahos on their reservation at Sand Creek in southeastern Colorado. His force consisted of 700 men, mainly volunteers in the First and Third Colorado Regiments. Plied with too much liquor the night before, Chivington and his men boasted that they were going to kill Indians. Once a missionary to Wyandot Indians in Kansas, Chivington declared, “Damn any man who sympathizes with Indians!…I have come to kill Indians, and believe it is right and honorable to use any means under God’s heavens to kill Indians.”

That fateful cold morning, Chivington led his men against 200 Cheyennes and Arapahos. Cheyenne Chief Black Kettle had tied an American flag to his lodge pole as he was instructed, to indicate his village was at peace. When Chivington ordered the attack, Black Kettle tied a white flag beneath the American flag, calling to his people that the soldiers would not kill them. As many as 160 were massacred, mostly women and children.

Custer’s Campaigns

At this time, a war hero from the Civil War emerged in the West.

George Armstrong Custer rode in front of his mostly Irish Seventh Cavalry to the Irish drinking tune, “Gary Owen.” Custer wanted fame, and killing Indians—especially peaceful ones who weren’t expecting to be attacked—represented opportunity.

General Philip Sheridan, Custer and his Seventh attacked the Cheyennes and their Arapaho allies on the western frontier of Indian Territory on November 29, 1868, near the Washita River. After slaughtering 103 warriors, plus women and children, Custer dispatched to Sheridan that “a great victory was won,” and described, “One, the Indians were asleep. Two, the women and children offered little resistance. Three, the Indians are bewildered by our change of policy.”

Custer later led the Seventh Cavalry on the northern Plains against the Lakota, Arapahos and Northern Cheyennes. He boasted, “The Seventh can handle anything it meets,” and “there are not enough Indians in the world to defeat the Seventh Cavalry.”

Expecting another great surprise victory, Custer attacked the largest gathering of warriors on the high plains on

June 25, 1876—near Montana’s Little Big Horn river. Custer’s death at the hands of Indians making their own last stand only intensified propaganda for military revenge to bring “peace” to the frontier.

Chief Sitting Bull was killed while being arrested, the U.S. Army’s Seventh Cavalry massacred 150 to 200 ghost dancers at

Wounded Knee, South Dakota.

For their mass murder of disarmed Lakota, President

Benjamin Harrison awarded about 20 soldiers the Medal of Honor.

Resilience

Three years after Wounded Knee, Professor Frederick Jackson Turner announced at a small gathering of historians in Chicago that the “frontier had closed,” with his famous thesis arguing for American exceptionalism. James Earle Fraser’s famed sculpture “End of the Trail,” which debuted in 1915 at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, exemplified the idea of a broken, vanishing race. Ironically, just over 100 years later, the resilient American Indian population has survived into the 21st century and swelled to more than 5 million people.

Execution of Dakota Sioux Indians in Mankato, Minnesota, 1862. (Credit: Library of Congress/Photo12/UIG/Getty Images)

Annuities and provisions promised to Indians through government treaties were slow in being delivered, leaving Dakota Sioux people, who were restricted to reservation lands on the Minnesota frontier, starving and desperate. After a raid of nearby white farms for food turned into a deadly encounter, Dakotas continued raiding, leading to the Little Crow War of 1862, in which 490 settlers, mostly women and children, were killed.

President Lincoln sent soldiers, who defeated the Dakota; and after a series of mass trials, more than 300 Dakota men were sentenced to death.

While Lincoln commuted most of the sentences, on the day after Christmas at Mankato, military officials hung 38 Dakotas at once—the largest mass execution in American history. More than 4,000 people gathered in the streets to watch, many bringing picnic baskets. The 38 were buried in a shallow grave along the Minnesota River, but physicians dug up most of the bodies to use as medical cadavers.

November 29, 1864, a former Methodist minister, John Chivington, led a surprise attack on peaceful Cheyennes and Arapahos on their reservation at Sand Creek in southeastern Colorado. His force consisted of 700 men, mainly volunteers in the First and Third Colorado Regiments. Plied with too much liquor the night before, Chivington and his men boasted that they were going to kill Indians. Once a missionary to Wyandot Indians in Kansas, Chivington declared, “Damn any man who sympathizes with Indians!…I have come to kill Indians, and believe it is right and honorable to use any means under God’s heavens to kill Indians.”

That fateful cold morning, Chivington led his men against 200 Cheyennes and Arapahos. Cheyenne Chief Black Kettle had tied an American flag to his lodge pole as he was instructed, to indicate his village was at peace. When Chivington ordered the attack, Black Kettle tied a white flag beneath the American flag, calling to his people that the soldiers would not kill them. As many as 160 were massacred, mostly women and children.

Custer’s Campaigns

At this time, a war hero from the Civil War emerged in the West.

George Armstrong Custer rode in front of his mostly Irish Seventh Cavalry to the Irish drinking tune, “Gary Owen.” Custer wanted fame, and killing Indians—especially peaceful ones who weren’t expecting to be attacked—represented opportunity.

General Philip Sheridan, Custer and his Seventh attacked the Cheyennes and their Arapaho allies on the western frontier of Indian Territory on November 29, 1868, near the Washita River. After slaughtering 103 warriors, plus women and children, Custer dispatched to Sheridan that “a great victory was won,” and described, “One, the Indians were asleep. Two, the women and children offered little resistance. Three, the Indians are bewildered by our change of policy.”

Custer later led the Seventh Cavalry on the northern Plains against the Lakota, Arapahos and Northern Cheyennes. He boasted, “The Seventh can handle anything it meets,” and “there are not enough Indians in the world to defeat the Seventh Cavalry.”

Expecting another great surprise victory, Custer attacked the largest gathering of warriors on the high plains on

June 25, 1876—near Montana’s Little Big Horn river. Custer’s death at the hands of Indians making their own last stand only intensified propaganda for military revenge to bring “peace” to the frontier.

Chief Sitting Bull was killed while being arrested, the U.S. Army’s Seventh Cavalry massacred 150 to 200 ghost dancers at

Wounded Knee, South Dakota.

For their mass murder of disarmed Lakota, President

Benjamin Harrison awarded about 20 soldiers the Medal of Honor.

Resilience

Three years after Wounded Knee, Professor Frederick Jackson Turner announced at a small gathering of historians in Chicago that the “frontier had closed,” with his famous thesis arguing for American exceptionalism. James Earle Fraser’s famed sculpture “End of the Trail,” which debuted in 1915 at the Panama-Pacific International Exposition in San Francisco, exemplified the idea of a broken, vanishing race. Ironically, just over 100 years later, the resilient American Indian population has survived into the 21st century and swelled to more than 5 million people.

November 29, 1864, a former Methodist minister, John Chivington, led a surprise attack on peaceful Cheyennes and Arapahos on their reservation at Sand Creek in southeastern Colorado. His force consisted of 700 men, mainly volunteers in the First and Third Colorado Regiments. Plied with too much liquor the night before, Chivington and his men boasted that they were going to kill Indians. Once a missionary to Wyandot Indians in Kansas, Chivington declared, “Damn any man who sympathizes with Indians!…I have come to kill Indians, and believe it is right and honorable to use any means under God’s heavens to kill Indians.”

That fateful cold morning, Chivington led his men against 200 Cheyennes and Arapahos. Cheyenne Chief Black Kettle had tied an American flag to his lodge pole as he was instructed, to indicate his village was at peace. When Chivington ordered the attack, Black Kettle tied a white flag beneath the American flag, calling to his people that the soldiers would not kill them. As many as 160 were massacred, mostly women and children.