It doesn't state that human investors are risk-anything. (Finance tries to avoid actual biology as much as possible) However - the market operates in a way that makes it appear the players are - on average - risk neutral.

MPT doesn't say anything about what the correct expected return of the market overall is - as I've pointed out - this is a parameter required by MPT, not a parameter that MPT computes.

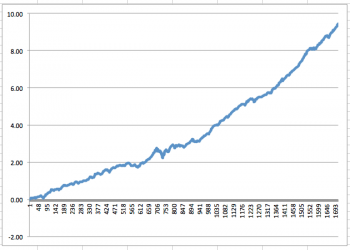

To put the absurdity of relying on past returns to predict future returns, take a look at SPY returns for the past year:

SPDR S&P 500 ETF Chart - Yahoo! Finance

If you look at it, you'll see lots of ups and down - but the clear overall trend is upward. The total increase is a little over 20%. There is a period of decline - during the fall of 2012 - but the prices recover and the market is again at pre-decline levels by February.

So based on this evidence, we should be able to conclude that although the price of the S&P 500 goes up and down, over any period that is at least 6 months long, it will at least retain its value, and on average, it will return 20%. Although we're only looking at one year of data - we can stagger 6 month samples so that we have as many samples as we like - and we could make a nice chart that shows the odds of winning or losing X dollars over certain intervals - and using all that, we should be able to convince people, like yourself, that the S&P 500 will always retain its value over 6 month periods.

Now do you see how absurd it is to base your expected 30 year return on barely more than 3X30 years of data? That's only 50% better than basing your expected 6 month return on a years worth of data, is it?

In fact if you look at the stock chart from a single day of a stock that did well on that day, you might conclude - using your method of reasoning - that the stock will go up and down but always retain or beat its value over 1 hour periods.

That's like saying "How do we know Western society works? We only have 200 years of data?" Perhaps we should crawl through the wormhole and measure the infinite multiverses, then we will have enough statistical data to see if the foundations of Western society are real.

If financial markets operate as if they are risk neutral, then why aren't the average returns the risk-free rate?

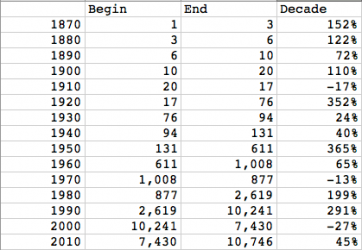

As for the past predicting the future, I do not believe that markets are efficient all the time, but I do believe they are efficient over long periods of time. In an efficient market, higher risk assets should earn more than lower risk assets over long periods of time. That's what theory says and that's what has happened in the past. Both theory and history tell us that those with long time frames are compensated for taking on risk. Thus, we should invest SS in the stock market like other pension funds and insurance companies, as do other national retirement schemes like in Europe and Canada.

The past 1 year of history has shown that 6 month periods the S&P 500 doesn't lose value. Do you dispute this claim?

If financial markets operate as if they are risk neutral, then why aren't the average returns the risk-free rate?