Taz

Gold Member

- Jul 8, 2014

- 22,876

- 2,119

- 190

- Banned

- #621

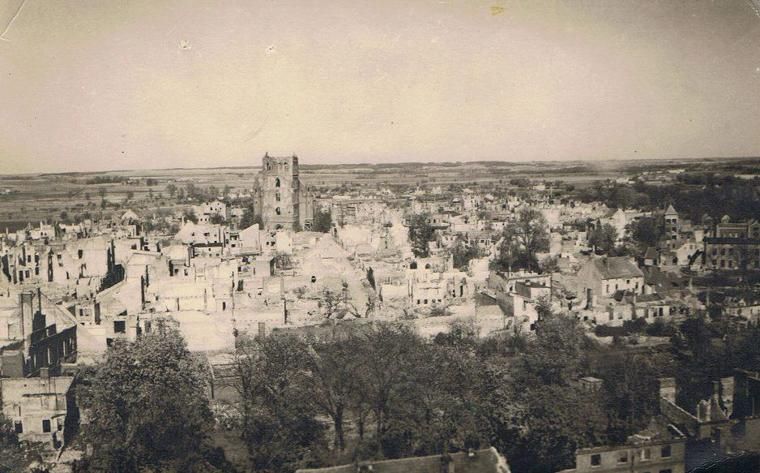

My white people have invented pretty much everything. Gone to the moon...Those are the best 3?That’s it? Not much there, brah.C'mon, what's the best thing a Pole ever invented? Name 3.

Dual Roter helicopter - Frank Piasecki.

First successful handheld movie camera - Aeroscope by Kazimierz Proczynski.

Television pioneered by 3 people of Polish heritage, Jan Szczepanik, Paul Nipkow, and Julian Ochorowicz.

Well, you only asked for 3, doof.

What has your ethnic heritage invented?

TopGaN

TopGaN