Ringo

Gold Member

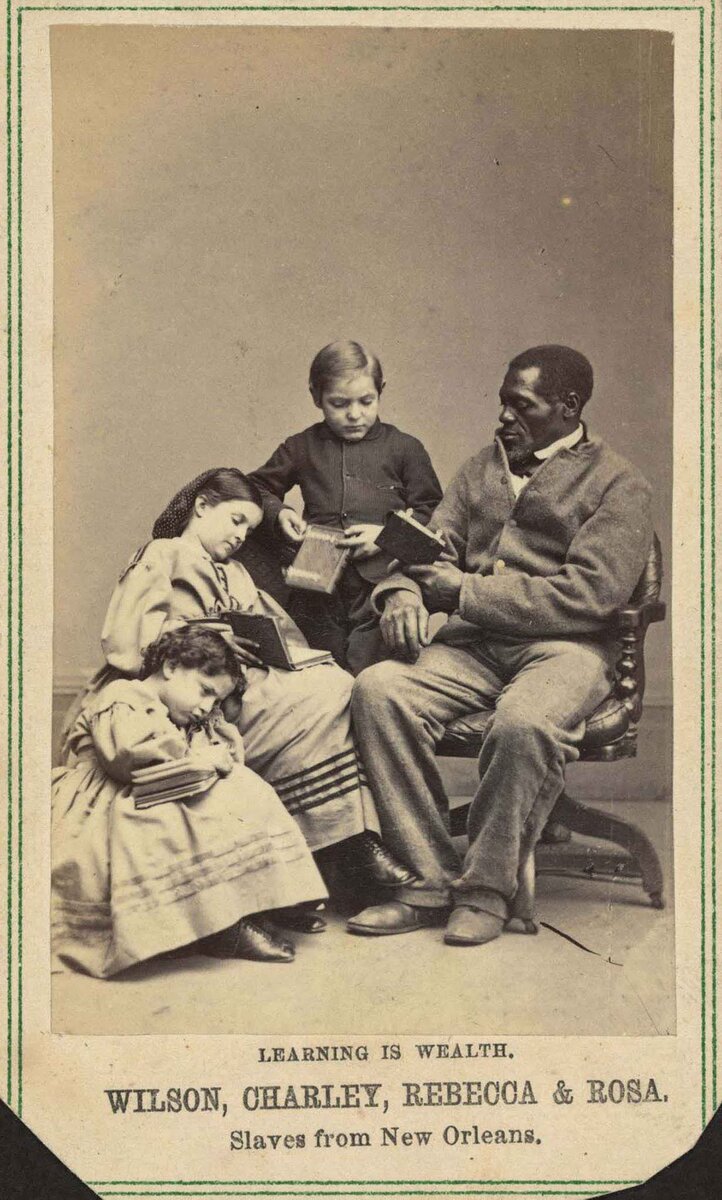

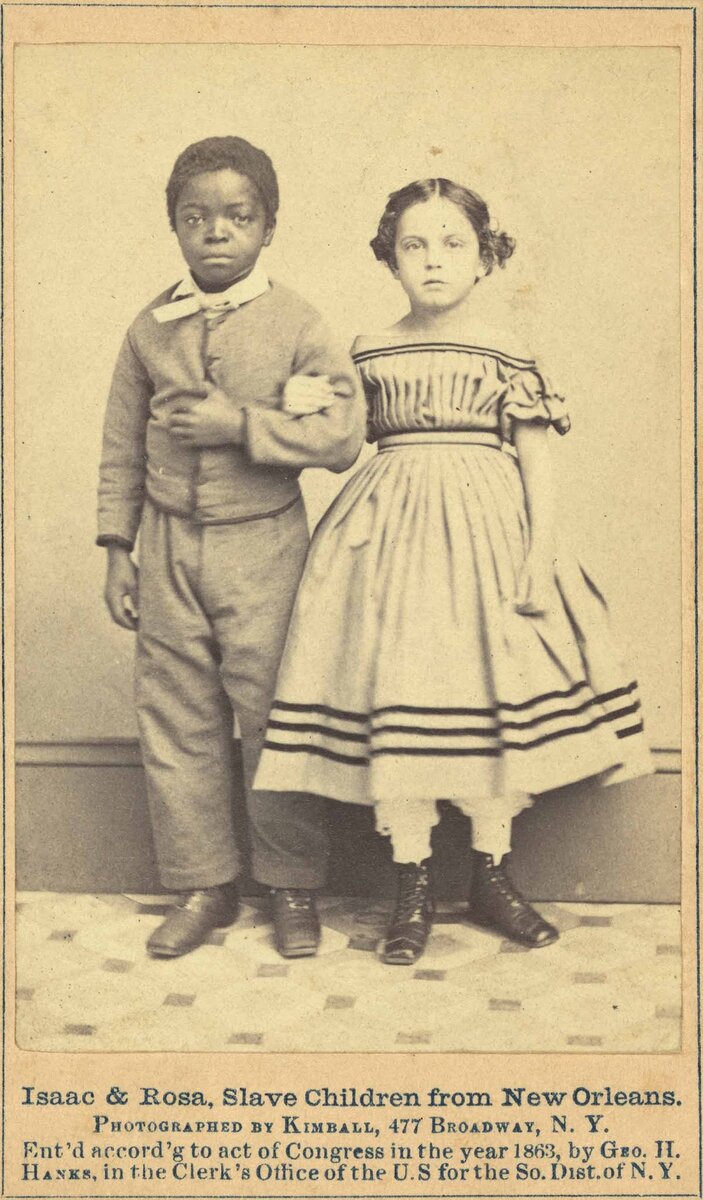

The children, a dark-skinned boy and a completely white girl with short, curly curls, looked on, scowling, as if not too trusting of the photographer. Other pictures surprised the public just as much: cute, but maybe too serious little kids with typically European features. That's why society was so shocked by their stories: These kids had one thing in common: they were freed slaves from the South.

On January 30, 1864, as the American Civil War was drawing to a close, the Harper Weekly began a series of publications under the slogan "Freed Slaves - White and Black. The publication had several purposes: first, to demonstrate to North Americans what the struggle was for, and second, to announce a fundraiser - the freed from slavery needed to establish a new life.

Source: RareHistoricalPhotos

Probably the editor who decided to carry out this action understood that the pictures would cause a bomb effect. Many people did not realize that slavery was not just a question of skin color. The existence of white slaves whose appearance was not unlike that of the masters raised many questions, and certainly not all of them were decent. Moreover, the fathers of light-skinned children traditionally remained in the shadows: only the slave mothers were known - pretty mulatto women whose dramatic stories turned out to be remarkably similar.

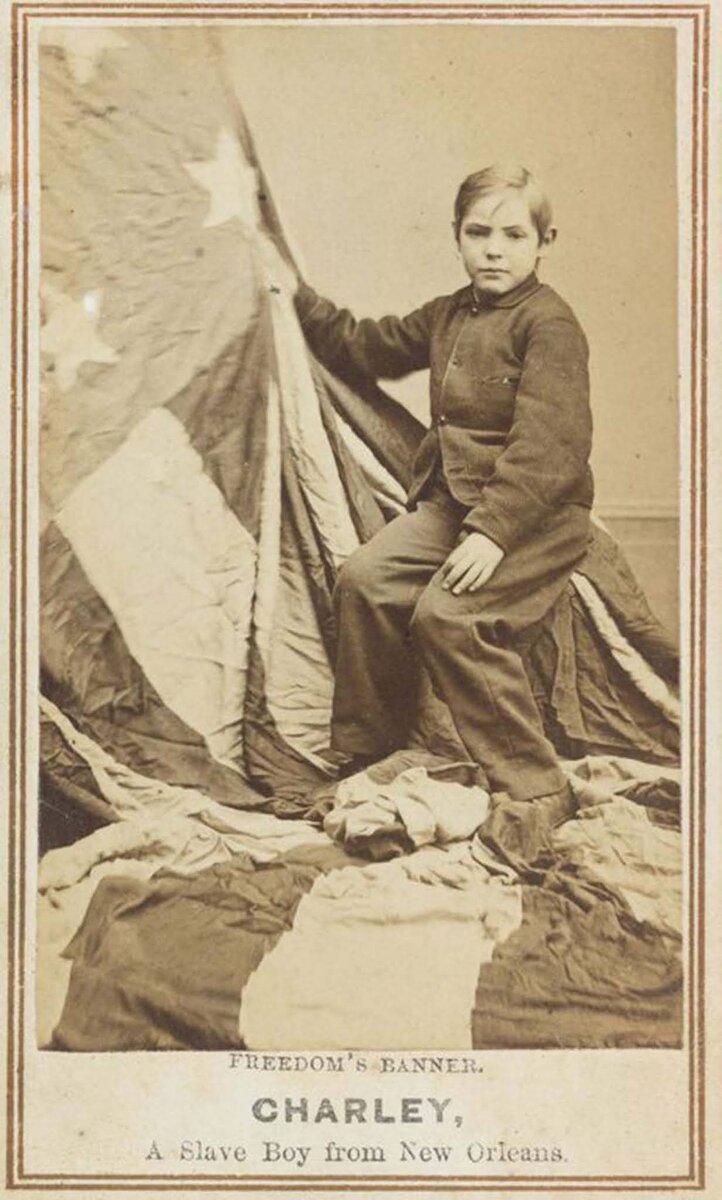

This time, however, reporters were not ashamed to bring the truth to light, in discreet terms so as not to offend readers' modesty by describing the origins of the babies. "Charlie Taylor of New Orleans was eight years old," the lines below the picture of a neatly combed boy with a firm chin read, "this white child was twice sold into slavery.

A note about Charlie revealed the twists and turns of his fate: first Alexander Weathers, the boy's father and owner, sold him and his mother to a slave trader named Harrison, who gave the "goods" he had received to Mr. Thornhill, who had fled when the Army of the North began to invade Louisiana. After his release, Charlie was sent to school, where he learned to read and write...Her son's successes certainly pleased his mother, but her heart still ached, for she knew nothing of her other children - her daughter had been sold to Texas, where she was lost, and the other boy might have been living with his father in Virginia.

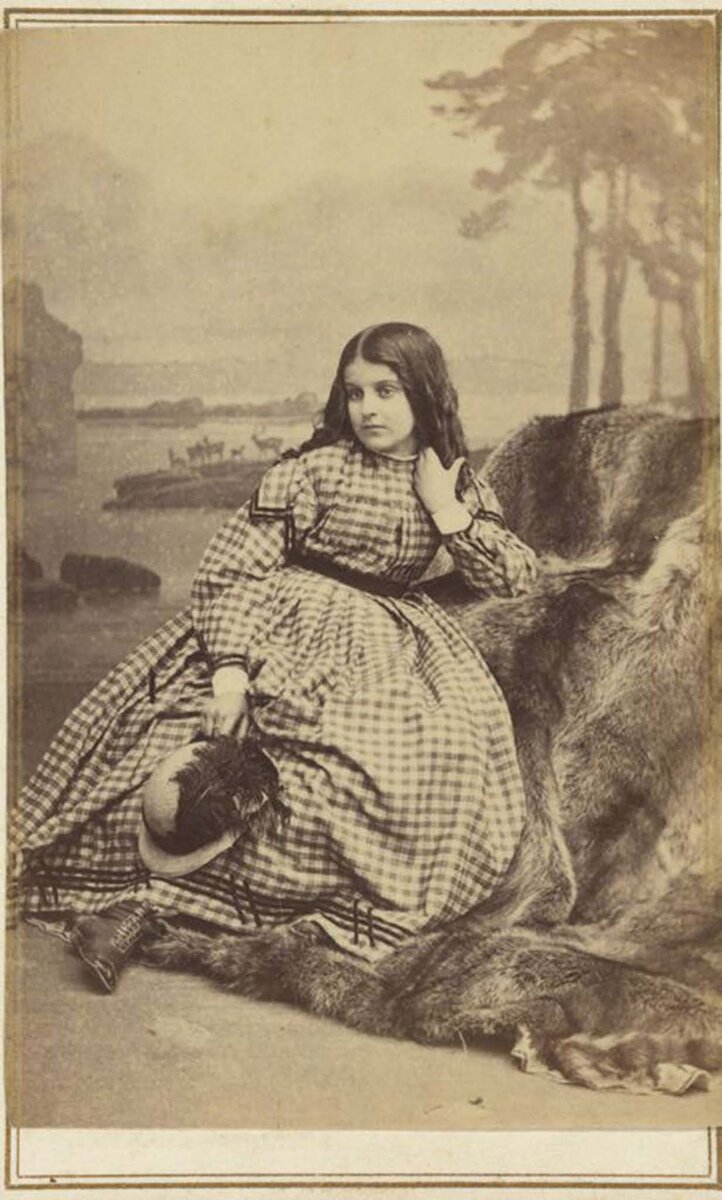

A different, but no less sad story might have been told by eleven-year-old Rebecca Huger, in whose features, too, no hint of African blood could be found. A slave in her father's house, she served her half-sister, a child of "proper" descent. Released along with her mother and grandmother, the girl also went to school, which gave hope that her future would turn out to be happy.

Rebecca Huger. Source: RareHistoricalPhotos

Like Charlie and Rebecca, other children were photographed: and, of course, what shocked Harper Weekly readers was the most contrasting couple, Isaac White and Rose Downs. They were different in appearance, but their slave past left its mark on each of their lives.

The magazine did not tell us about eight-year-old Isaac's family, but about six-year-old Rose we know that her father joined the Army of the North and that her mother, a "fair mulatto," lived in poverty and worked hard to feed her five children (two white daughters and three "darker" sons).

The campaign launched in the 1860s is said to have been successful: at the very least, articles soliciting donations and pictures of children being sold off raised money to build several schools.

However, despite the obvious absurdity of the "one drop of black blood rule," the principle that a person with at least one black ancestor was considered black, attitudes toward African Americans, both white and dark, in the United States left much to be desired for a long time. It was not until a century later, in 1960, that the first African-American girl, Ruby Bridges, went to the same school as white children, causing incredible protests: teachers refused to teach her, classmates refused to study with her, and their parents threatened to kill her.

On January 30, 1864, as the American Civil War was drawing to a close, the Harper Weekly began a series of publications under the slogan "Freed Slaves - White and Black. The publication had several purposes: first, to demonstrate to North Americans what the struggle was for, and second, to announce a fundraiser - the freed from slavery needed to establish a new life.

Source: RareHistoricalPhotos

Probably the editor who decided to carry out this action understood that the pictures would cause a bomb effect. Many people did not realize that slavery was not just a question of skin color. The existence of white slaves whose appearance was not unlike that of the masters raised many questions, and certainly not all of them were decent. Moreover, the fathers of light-skinned children traditionally remained in the shadows: only the slave mothers were known - pretty mulatto women whose dramatic stories turned out to be remarkably similar.

This time, however, reporters were not ashamed to bring the truth to light, in discreet terms so as not to offend readers' modesty by describing the origins of the babies. "Charlie Taylor of New Orleans was eight years old," the lines below the picture of a neatly combed boy with a firm chin read, "this white child was twice sold into slavery.

A note about Charlie revealed the twists and turns of his fate: first Alexander Weathers, the boy's father and owner, sold him and his mother to a slave trader named Harrison, who gave the "goods" he had received to Mr. Thornhill, who had fled when the Army of the North began to invade Louisiana. After his release, Charlie was sent to school, where he learned to read and write...Her son's successes certainly pleased his mother, but her heart still ached, for she knew nothing of her other children - her daughter had been sold to Texas, where she was lost, and the other boy might have been living with his father in Virginia.

A different, but no less sad story might have been told by eleven-year-old Rebecca Huger, in whose features, too, no hint of African blood could be found. A slave in her father's house, she served her half-sister, a child of "proper" descent. Released along with her mother and grandmother, the girl also went to school, which gave hope that her future would turn out to be happy.

Rebecca Huger. Source: RareHistoricalPhotos

Like Charlie and Rebecca, other children were photographed: and, of course, what shocked Harper Weekly readers was the most contrasting couple, Isaac White and Rose Downs. They were different in appearance, but their slave past left its mark on each of their lives.

The magazine did not tell us about eight-year-old Isaac's family, but about six-year-old Rose we know that her father joined the Army of the North and that her mother, a "fair mulatto," lived in poverty and worked hard to feed her five children (two white daughters and three "darker" sons).

The campaign launched in the 1860s is said to have been successful: at the very least, articles soliciting donations and pictures of children being sold off raised money to build several schools.

However, despite the obvious absurdity of the "one drop of black blood rule," the principle that a person with at least one black ancestor was considered black, attitudes toward African Americans, both white and dark, in the United States left much to be desired for a long time. It was not until a century later, in 1960, that the first African-American girl, Ruby Bridges, went to the same school as white children, causing incredible protests: teachers refused to teach her, classmates refused to study with her, and their parents threatened to kill her.

Last edited: