Sixties Fan

Diamond Member

- Mar 6, 2017

- 56,702

- 10,781

- 2,140

- Thread starter

- #101

Today in Jewish History

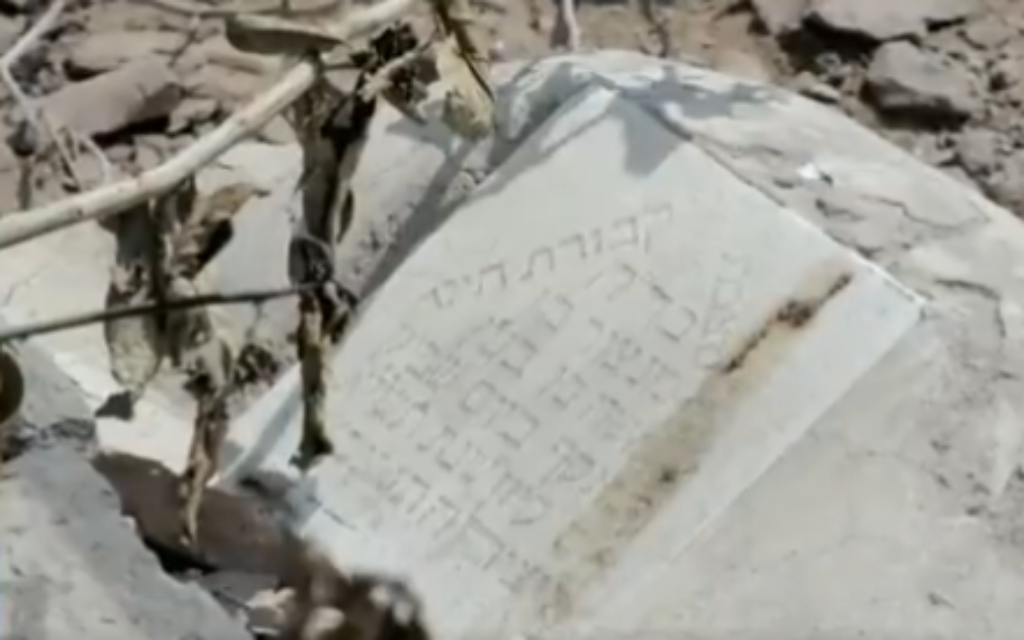

• Hebron Massacre (1929)Sixty-seven Jewish men, women and children were slaughtered, and scores wounded, raped and maimed, by their Arab neighbors in the city of Hebron, who rioted for three days amid cries of "Slaughter the Jews." The killings began on Friday afternoon, 17 Av, and most of the victims lost their lives on Shabbat, 18 Av. The survivors were forced to evacuate to Jerusalem, and the ancient Jewish community of Hebron, which had lived in relative peace in the city for hundreds of years, was not revived until after Israel's capture of Hebron in the 1967 Six Day war.