Womans studies is usually a base degree to other subjects like woman's health,...

As for your corporate tax thing, hey dumbass what is the corporate tax rates in Eastern Europe... Close to 0%...

The effective rates in France are below 10%...

I suppose if you got an education you might have known that...

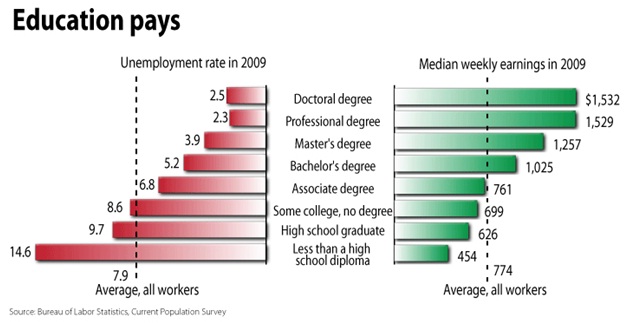

Is College Worth Your Time and Money

Problem with your research is you actually quote none of it. I find this surprising from someone who has some much education behind him.

You would get seriously marked down in exams or paper for just pulling those facts right out of your ass.

Inequality and Ability:

Using data from the NLS, Murnane et al. (1995) report that basic cognitive skills learned prior to high school had a much larger impact on the wages for 24-year-old men and women in 1986 than in 1978 in the United States. The cognitive measures they use are basic skills such as following directions, facility with fractions and decimals, and interpretation of line graphs. In other research, Ferguson (1993) finds that adding basic skills into the wage regression wipes out the estimated growth in the return to schooling during the 1980s in the United States. Using the AFQT score as a measure of ability, Ferguson shows that the return to basic skills rises during the 1980s and converges within all education groups. . . .

In contrast to the literature summarized in Section 2, these results are the first to show that a measure for mental ability is becoming increasingly important within sectors over time. The addition of IQ also serves to wipe out the limited increase in the return to education in the professional sector, as well as decreasing the estimated increase in the return to education in the service sector: the return to education in the service sector increases from 9% to 11% instead of 9% to 14% without IQ. However, the inclusion of IQ into the analysis does not meaningfully affect the size or trend of the residual variance within each of the three occupational sectors. . . .

The addition of IQ into the analysis reduces the returns to education, particularly for 1992, so that there is virtually no appreciable increase in the return to education in either sector after controlling for IQ. The increasing return to education found in Table 6 is now picked up by the increasing return to IQ in the professional and service sectors. . . .

The results show that ‘‘residual inequality’’ is increasing over time due to an increasing emphasis on mental ability and/or the general unobservable skill within each occupation. Consequently, the trend in residual inequality is being driven by technology not only dispersing the variances of abilities, but more importantly it is increasingly emphasizing general skills versus sector-specific skills over time.

I'm loaded for bear on papers dealing with labor market dynamics. Here's one that you might like:

The College Wage Premium, Overeducation, and the Expansion of Higher Education in the UK

Although there is little evidence that, on average, the college premium has shown any significant trend changes in recent years, despite the large increase in the flow of graduates into the labour market, we have shown that there seems to have been a marked fall in returns for recent cohorts across almost all subjects for both men and women. Breaking this down further into graduates in high SOC jobs compared to low we see that the fall is entirely confined to the latter. Indeed, we find that for men, and especially for women, there is a large increase in the proportion with maths and engineering degrees getting graduate jobs and that, conditional on this, the return is rising. This would be consistent with the falling numbers in the flow of such graduates.

Here's another one. Note the same pattern is found in Hong Kong as was found in the UK - graduates from earlier cohorts earned larger returns on their educations than do recent cohorts.

Shrinking Earnings Premium for University Graduates in Hong Kong: The Effect of Quantity or Quality?

In 1989, the Hong Kong government embarked on a program to increase the provision of first-year first-degree places from 7 percent of the 17–20 age cohort to 18 percent. The number of university students doubled in five years. Since university places are tightly controlled by the government, the expansion program represents an exogenous increase in supply of university graduates to the labor market. This paper shows that the increase in supply has brought about a decline in the earnings premium for college workers. Moreover, the decline is more substantial among younger workers than among older workers. We also find that locally educated university graduates used to earn significantly more than did overseas graduates. Their earnings advantage, however, had declined between 1986 and 2001, particularly among the younger age group. These observations suggest that the decline in the university earnings premium is probably more the result of declining quality of university graduates than of a labor market crowding effect.

Sorting out the reasons for the declining college premium has implications for public policy. If the crowding effect is the major cause, this means the demand for college workers is rather inelastic, so that the labor market cannot accommodate a large increase in supply of college workers without reducing their wage. In that case, policy makers may have to re-think whether Hong Kong should continue its policy of expanding post-secondary education. If declining quality of university graduates is the major cause, then the policy focus should fall on how to improve the quality of higher education.

Now that paper didn't control for cognitive ability but when considered in conjunction with the findings of this paper, a fuller picture does emerge:

Ability, Educational Ranks, and Labor Market Trends: The Effects of Shifts in the Skill Composition of Educational Groups

This paper uses educational ranks – cohort-specific relative rankings in educational attainment – as a control for changes in the composition of educational groups.5 This approach assumes that individuals in different cohorts with the same educational rank, i.e. those in the same place in their cohort’s educational attainment distribution, have about the same level of ability. Thus, the ability (or unobserved skill) of high school graduates in 1940 was more like that of college graduates in 1996 than their counterpart high school graduates.

As mentioned above, accounting for these changes in the composition of educational groups profoundly changes our picture of the U.S. labor market. Increases in the college/high school differential are considerably smaller but more concentrated among younger workers, and it is more difficult to argue that the earnings of less educated groups have deteriorated. . . .

Interestingly, when the data are sorted by educational quintile, a remarkably different pattern emerges.27 For example, between 1969 and 1989 high school graduates and dropouts experienced declines in their weekly earnings of 2.4 and 8.7 percent, respectively, while the weekly earnings of those in the lowest three quintiles rose by an average of 8.5 percent. These findings suggest that changes in the composition of the less educated may explain their widely documented declines in earnings. Changes in composition also appear to affect differences between educational groups. For example, the log difference between college and high school graduates increased by 8.2 percentage points between 1969 and 1989, while the difference between the highest and middle quintiles decreased by 5.4 percentage points. Consistent with the finding in Table 1 of increasing differences in ability (or unobserved skill) between college and high school graduates, accounting for changes in composition appear to explain much of the recent increase in earnings differentials between college and high school graduates. . . .

One might wonder whether the strong results for the effects of changes in the composition of educational groups on weekly earnings education differentials hold for other outcomes, such as employment and annual earnings. In fact, the effects of including educational ranks are considerably stronger for these outcomes. For annual employment, education differentials are slightly negative once educational ranks are included suggesting that employment differentials are more closely related to a person’s educational rank than their educational attainment. Moreover, accounting for changes in composition of educational groups results in change in the 1969-1989 college/high school annual employment differential switching from a 1.3 percentage point increase to a 0.9 percentage point decrease.

Similarly, the results for annual earnings are quite strong. For example, the difference in annual earnings between college graduates and high school dropouts increases by 32.6 percentage points between 1959 and 1989. After accounting for changes in the composition of educational groups, this increase falls to a dramatically smaller 11.5 percentage points. Without question, accounting for changes in the composition of educational groups generates a very different picture of the U.S. labor market.

In both Hong Kong and the United Kingdom, and the US too, college graduates from earlier generations earned larger rewards for their education than does the present generation and this last paper fills in the blanks, colleges are now drawing deeper into the intellectual talent pool in order to fill their classrooms. When colleges only skimmed off the top of the talent barrel, then high intelligence and college education became synonymous. When colleges end up pulling the top 60% of the high schools class instead of the top 6% then the linkage between high intelligence and college degree is broken.

The issue that you and I are addressing is how much labor market reward is generated by the black box of college education. The UK data showed that math and engineering graduates do well for themselves because they're a small proportion of total graduates and both have skills desired by the market. This attribute is even observed in the GRE test data for those students who think about applying to

graduate school:

Those who do not go on to graduate school are drawn atypically from the upper tail of the GRE quantitative distribution and the lower tail of the GRE verbal distribution, both of which are expected to raise their earnings. On the other hand, those who go on to graduate school are drawn disproportionately from the lower tail of the quantitative GRE distribution and from the upper tail of the GRE verbal distribution, both of which lower their opportunity costs of graduate school.

All those psychology classes and art history classes and sociology classes, well, they're not really doing much for students in terms of increasing their labor market skills and returns to wages. Some specific skills are rewarded and that's what research is picking up as the residual effect after controlling for cognitive ability. Now sure, an art history major who gets hired by an art museum will earn a return on her studies of art history, but if she is hired to be an advertising copywriter, the advertising agency isn't hiring her for her knowledge of art, they're hiring her based on her documented ability to be admitted into college, having the perseverance to complete the degree and on her class rank and the reputation of her college. She's bought herself a credential. The employer only cares about her ABILITY, not her education. The credential signals information about ability.

Actually my proof is really simple... Why do employers ask for degrees when they can just give people an IQ test and start them on minimum wage and have them running their company...

Because Civil Rights legislation has made it illegal to do so. Companies don't like getting sued for discrimination, which is what happens when they hire by IQ tests. This was decided by the Supreme Court back in the 1970s. College degrees are a proxy measure of intelligent. What a 2 hour test can determine is now measured by a very expensive degree which takes 4 years of time to acquire.