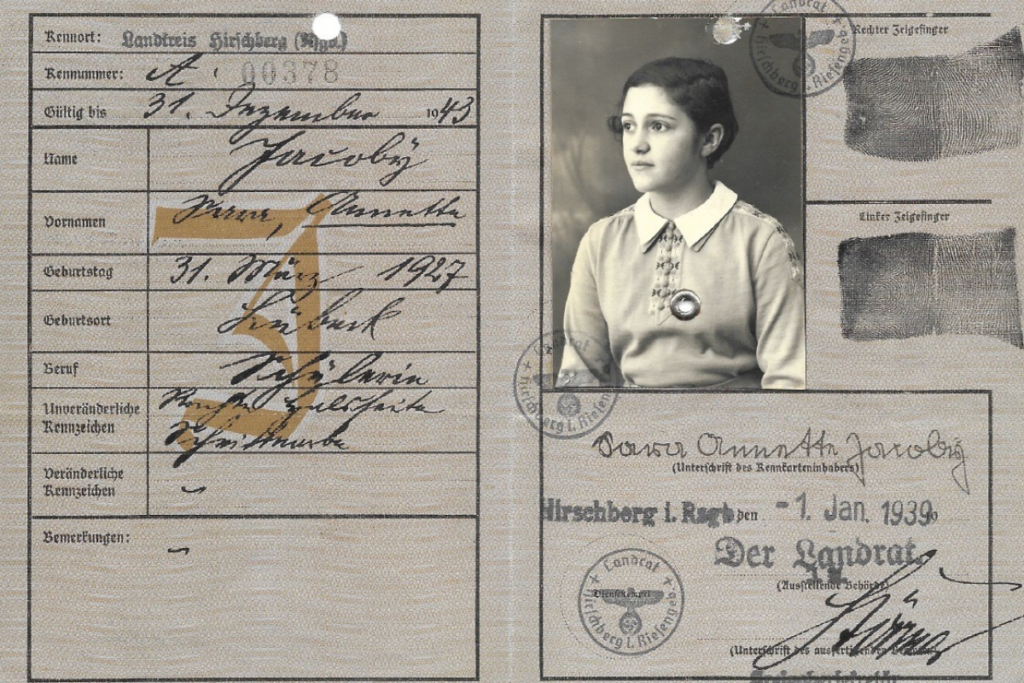

Oma was forced to flee from her homeland Germany with her parents in 1939, leaving behind family, friends and the land she had grown up in. They settled in a village called Livingstone, near the Victoria Falls in Northern Rhodesia (now Zambia), a destination chosen by dropping a pencil on an open map of territories that were still accepting refugees. They quickly realized that their lives were going to look very different, and although it was jarring – the Rosenthal china and piano they insisted on bringing to Africa were instantly useless – they had to adapt and accept their new reality.

Back in Germany, life had been becoming increasingly unbearable under Hitler’s rule. Its culmination came when my Oma was hidden in a village orphanage to protect her after her father was arrested during

Kristallnacht. Her mother somehow persuaded the authorities to release him, and the family left for Africa shortly after. Even in Africa, away from threat of persecution, it was difficult for them to ever return to feeling completely safe. This experience, and her later journey to England in her 20s where she again had to assimilate into a new culture in order to be accepted, led to the development of my Oma’s mantra:

Adapt, always adapt.This mantra represents who Oma was to the core, someone with a fiercely positive outlook on life in spite of the traumatic events she lived through. She felt neither safe nor able to openly celebrate her heritage, and yet she continued to see life as being made up of adventures. She managed to balance day-to-day survival with deeper appreciation for and enjoyment of life. I think of my Oma, and I remember her light, her joy and her optimism. I feel so grateful to have had the privilege of learning from her.

I didn’t know that

joining the Jewish Society would be something I would find so intimidating, and I didn’t know that there were so many complicated fears and anxieties involved in being Jewish. I also didn’t know that I would meet so many wonderful people, people that are kind, welcoming and understanding. I only discovered this last part because I followed Oma’s example, and kept going with optimism.

I still have fears that I’m not Jewish enough, that I’m not understanding references to what seem to be universal experiences. I’m still calling my mum, asking her for advice and reassurance. I didn’t grow up with Hanukkah, or Passover, and I’ve never been to a Bar/Bat Mitzvah. But I’m learning to adapt, both at home and at university, where I’m starting to make a second home. There is so much beauty and love within being Jewish, I feel so comforted by the culture my Oma was forced to hide. Every time I learn about a new holiday or practice, I am genuinely excited to adopt it into my life – with the exception of Yom Kippur and some elements of Passover – I

really love bread.

(full article online)

When I started university last September, I knew that I wanted to join the Jewish Society, and that I wanted to use it as an opportunity to get in touch with my heritage. I went to the first social, panicked and called my mum asking if I actually ought to be there at all. Everyone […]

www.heyalma.com