Part 4

Postcard depicting Hilsner at trial

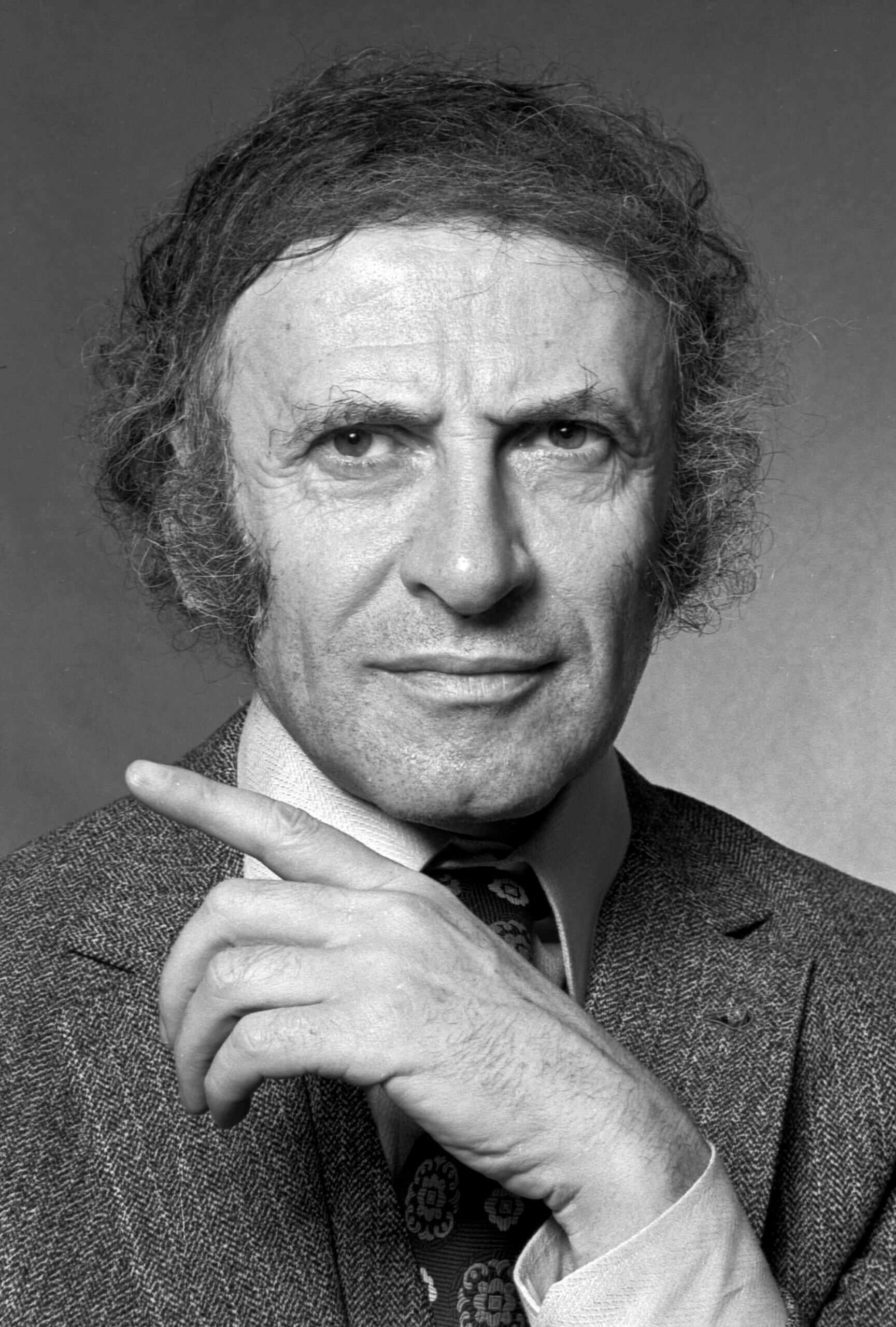

Masaryk’s involvement in the case was a gutsy and unpopular move, as he put his reputation, his career, and his future on the line to defend the Jewish people in general, and Hilsner in particular, against the loathsome blood libel. Standing virtually alone in the face of overwhelming hostility, he was vilified by the Church and the Czech media; his pamphlets were banned, and officials at the Czech University forced him to take a leave of absence from his teaching. Known as the “George Washington of Czechoslovakia,” Masaryk proved to be a good friend of the Jews, not only during the Hilsner Affair, but also during his term as president of Czechoslovakia (1918 – 1935).

During the Masaryk era, Czechoslovakia belonged to a small group of states that officially recognized Jewish nationality and granted Jews full civil rights. Masaryk was a strong supporter of Zionism; as he said in 1918:

The Jews will enjoy the same rights as all the other citizens of our State . . . As regards Zionism, I can only express my sympathy with it and with the national movement of the Jewish people in general, since it is of great moral significance. I have observed the Zionist and national movement of the Jews in Europe and in our own country and have come to understand that it is not a movement of political chauvinism, but one striving for the rebirth of its people.

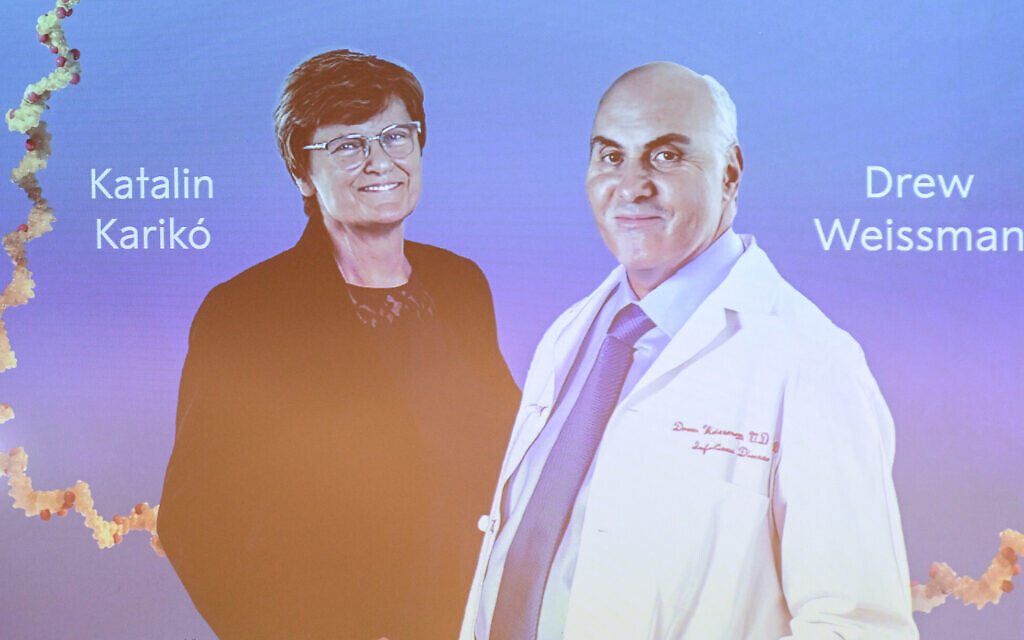

Famous postcard of Rav Sonnenfeld escorting Masaryk through the streets of Jerusalem (1927).

In 1927, Masaryk visited Eretz Yisrael where, upon his arrival in Jerusalem, he was greeted with great affection by a massive crowd that included representatives of virtually every sector of the Jewish community. Heading his reception was Rav Yosef Chaim Sonnenfeld, chief rabbi of the Edah HaCharedit and a staunch opponent of political Zionism, who escorted the president through the throngs and the decorated streets. In recognition of his friendship with the Jews, the kibbutz Kfar Masaryk in the Galilee was named for him.

In response to Masaryk’s filing and the publicity generated by his pamphlets, the high court ordered the medical faculty at the Czech University in Prague to review the findings of the original medical commission. In its subsequent report, the faculty issued a severe critique of the medical examiners’ criminological work, including particularly their false claim that the amount of blood at the site of Anežka’s corpse was materially less than the amount that should have been found in a violent death. Accordingly, the court nullified the original verdict and remanded the case to the Písek court for a new trial, but now Hilsner faced a second murder accusation: Marie Klímová, a servant who had disappeared on July 17, 1898. When a female body was found on October 27 in the same forest where Anežka’s body had been found, the decomposition was so advanced that the authorities could not even determine whether the girl had been murdered; nonetheless, the condition of the corpse bore some resemblance to that of the Anežka Hrůzová crime scene, which the prosecutor decided constituted sufficient basis for them to charge Hilsner with the murder.

The Supreme Court had expressly rejected the ritual murder theory, so the prosecutor, forced to find a different theory, decided to try Hilsner as a sexual predator, and the prosecution was materially assisted by the testimony of witnesses who, overnight, somehow became more certain in their testimony. For example, a witness who had previously testified that they had seen Hilsner with a knife, but could not provide any description of the weapon, was now adamant that the blade was a

schochet’s knife (used by Jews in their ritual kosher slaughtering), and the “strange” Jews who a key witness had claimed she had seen accompanying Hilsner and whom she could not describe were now described in great detail. When Hilsner’s counsel showed the witnesses transcripts of their testimony at the first trial and asked them to compare with it their new testimony at the second trial, they alleged that either they had been intimidated by the judge or that their statements had been incorrectly transcribed.

After a 17-day retrial ending November 14, 1900, Hilsner was convicted of both murders and sentenced to death, but the death sentence was commuted to life imprisonment in 1901 by Emperor Franz Josef. Hilsner’s requests for a new trial were all denied and, although he was finally pardoned by Emperor Charles I on March 24, 1918 as one of his first acts upon succeeding to the Hapsburg throne, the conviction was never annulled. (In 1919, the organization for combatting antisemitism in Austria made a futile appeal for a new trial to clear his name, but the attempt failed.) Anežka Hrůzová’s killer was never found and, although suspicions have been directed at various individuals over time, no one else was ever charged with the murders.

It is interesting to note that in writing

The Trial, the celebrated novel in which a man is prosecuted by an unknown authority and is tried and convicted of a crime that is never disclosed to him, Franz Kafka was inspired by contemporary historical events, including particularly the Hilsner Affair, which took place in his own country. Allegations that Anežka Hrůzová’s cut throat was consistent with

schechita requirements to make an animal kosher must have hit Kafka, the 16-year-old grandson of a

shochet, particularly hard, and he was also likely affected by his father’s active involvement in the Central Association for the Preservation of Jewish Affairs, which took a strong public stand in support of Hilsner and against the blood libel hoax.

According to Gustav Janouch, a Czech poet best known for his memoir

Conversations with Kafka, Kafka cited the Hilsner Affair as the starting point of his awareness of the Jewish condition: “a despised individual, considered by the surrounding world as a stranger, only tolerated – in other words, a pariah.” In Kafka’s correspondence with Milena Jesenska, one of the great loves of his life, he makes a direct reference to the Hilsner affair as a definitive example of the irrationality of antisemitism: “I cannot understand how people came to this idea of ritual murder.”

A police search of Hilsner’s house yielded no incriminating evidence, and he maintained that he had left the city on the afternoon of the murder long before it could have been committed.

www.jewishpress.com