Sixties Fan

Diamond Member

- Mar 6, 2017

- 73,291

- 12,706

- 2,290

- Thread starter

- #381

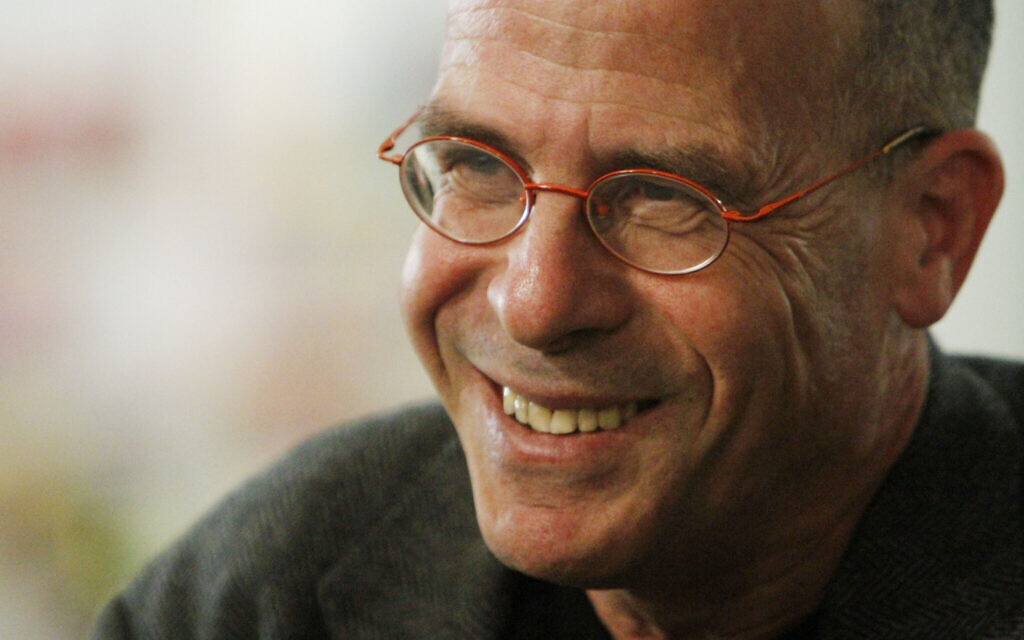

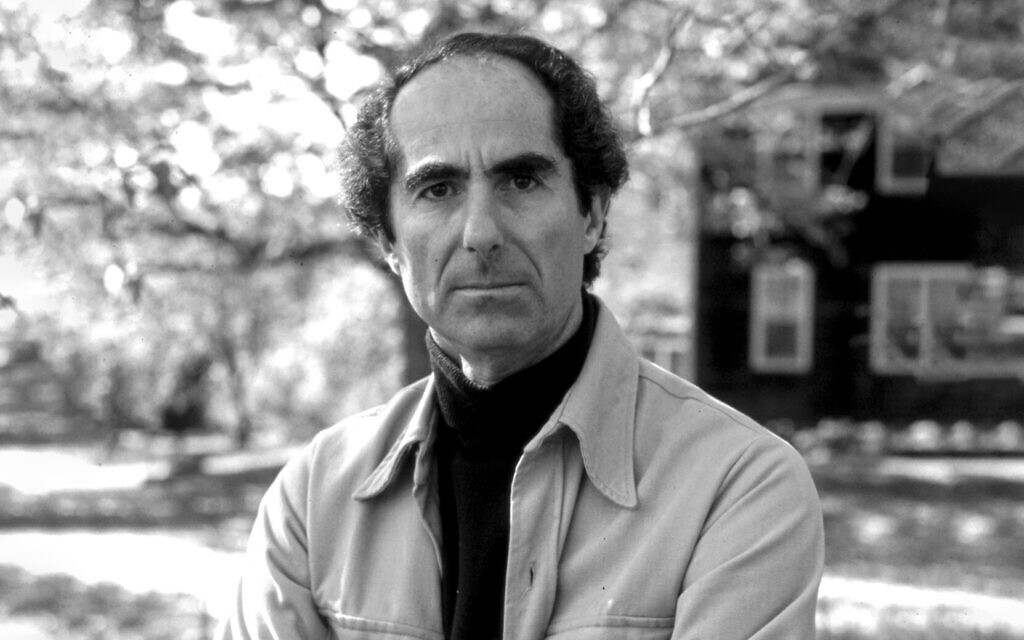

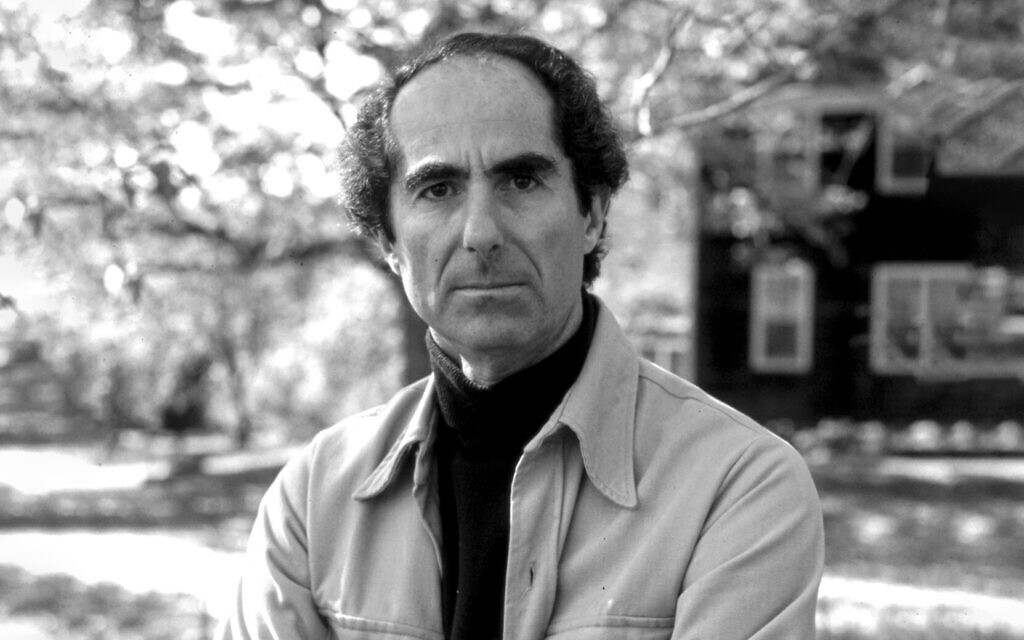

Even if you’ve never been there, you might have an opinion about Newark, New Jersey. For some, it is the quintessence of urban decay. For others, it is a vibrant community of creativity and entrepreneurship. For Philip Roth, arguably the greatest Jewish-American author to dip his quill in ink, it was home.

Since most of his work was in some way autobiographical, not much in his vast oeuvre doesn’t touch upon Newark in some way. So for three days in mid-March, the New Jersey Performing Arts Center (NJPAC), located in the heart of downtown Newark, will celebrate the hometown chronicler with “Philip Roth Unbound: Illuminating a Literary History.”

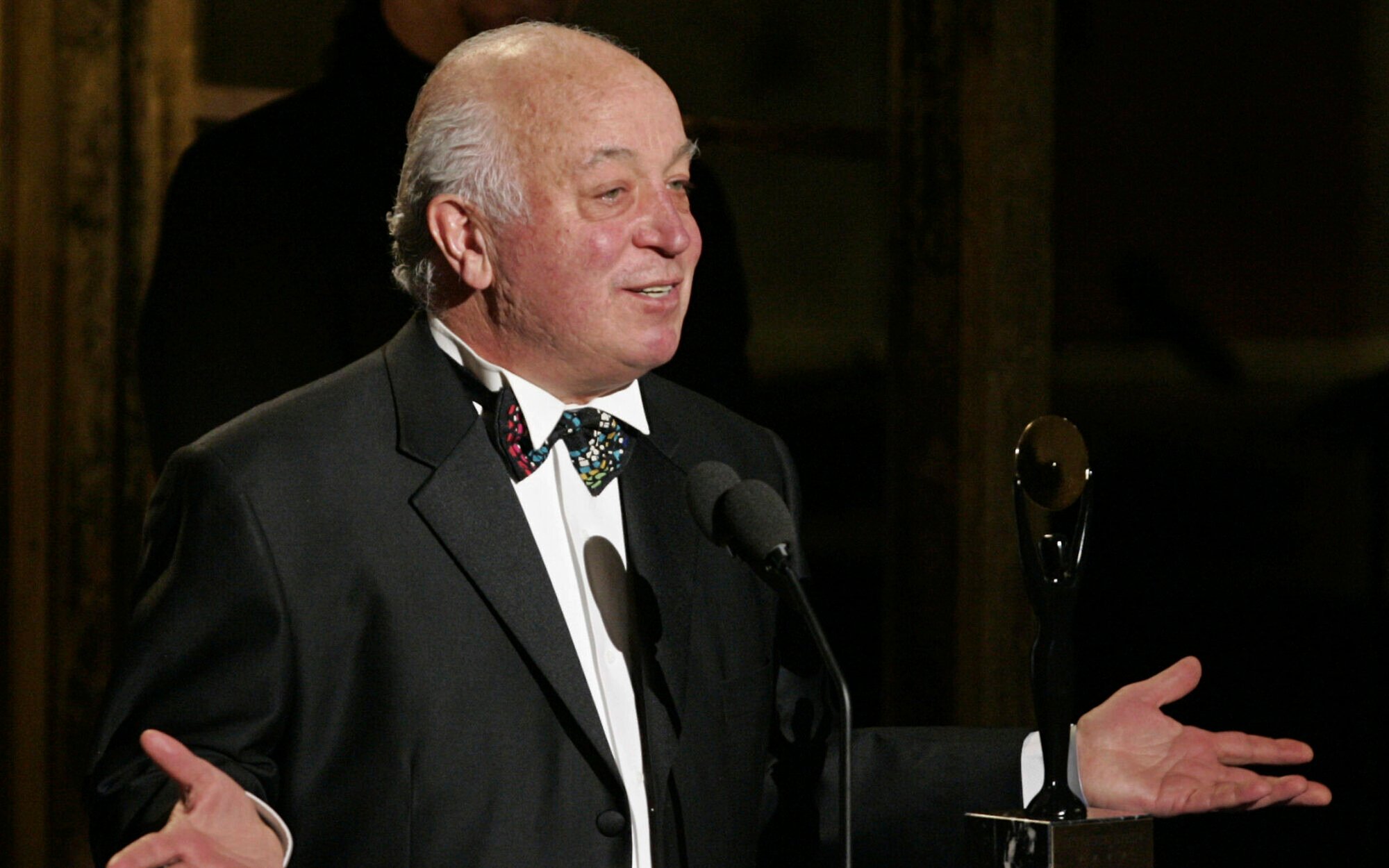

The weekend festival will feature readings of his work by celebrities (Matthew Broderick, Peter Riegert, Morgan Spector), two looks at theatrical presentations of his work (“Sabbath’s Theater” with John Turturro, “The Plot Against America” with Sam Waterston, S. Epatha Merkerson, Tony Shalhoub, Eric Bogosian and others), plus a slew of writers and intellectuals getting into the nitty gritty of Roth’s books, analyzing them in ways that would cause Alexander Portnoy to complain.

The panels will be audio recorded and will, pending permission, be made available in some kind of podcast form.

The weekend will expand out of NJPAC’s fancy digs (at the intersection of the very-Newark Sarah Vaughan Way and Wayne Shorter Way) for an audio-guided tour of the Newark Public Library, an evening of comedy at a Jewish delicatessen, and even a bus tour visiting locations from Roth’s life and his fiction. (As if we can tell the difference at this point!)

(full article online)

www.timesofisrael.com

www.timesofisrael.com

Since most of his work was in some way autobiographical, not much in his vast oeuvre doesn’t touch upon Newark in some way. So for three days in mid-March, the New Jersey Performing Arts Center (NJPAC), located in the heart of downtown Newark, will celebrate the hometown chronicler with “Philip Roth Unbound: Illuminating a Literary History.”

The weekend festival will feature readings of his work by celebrities (Matthew Broderick, Peter Riegert, Morgan Spector), two looks at theatrical presentations of his work (“Sabbath’s Theater” with John Turturro, “The Plot Against America” with Sam Waterston, S. Epatha Merkerson, Tony Shalhoub, Eric Bogosian and others), plus a slew of writers and intellectuals getting into the nitty gritty of Roth’s books, analyzing them in ways that would cause Alexander Portnoy to complain.

The panels will be audio recorded and will, pending permission, be made available in some kind of podcast form.

The weekend will expand out of NJPAC’s fancy digs (at the intersection of the very-Newark Sarah Vaughan Way and Wayne Shorter Way) for an audio-guided tour of the Newark Public Library, an evening of comedy at a Jewish delicatessen, and even a bus tour visiting locations from Roth’s life and his fiction. (As if we can tell the difference at this point!)

(full article online)

Even Portnoy wouldn’t complain about Newark gala for provocative author Philip Roth

Actors John Turturro, Matthew Broderick and Tony Shalhoub, plus a slew of appropriately edgy writers, will head up a 3-day literary festival for the hometown hero March 17-19