Yet technology to see and detect such did not exist in 1908 ...

Nor were the results of the blast significantly different from those of a nuke detonation

It does exist today. In case you did not realize, it is no longer 1908 (1909 if you watch Ghostbusters).

And FYI, I have watched the tracks of meteors on military RADAR. It looks nothing like a missile track. It does cause us to sit up and take notice because they are going really-really fast. And if your potential source and targets are east-west of each other they can indeed resemble an inbound missile. But they are still completely wrong, and within maybe 10-15 seconds we always knew what they really were. And that was not a missile.

Nothing else matters, you are not going to confuse a missile for a meteor.

So, why are you then going off about other silly things that have nothing to do with missiles? Or much of anything else?

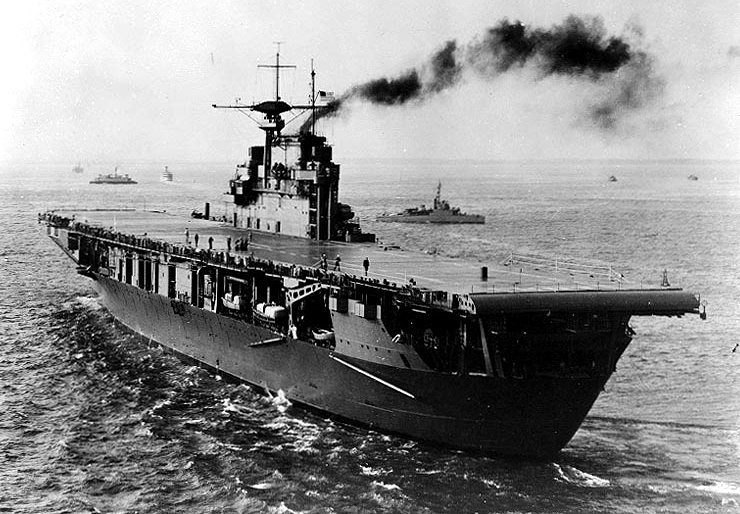

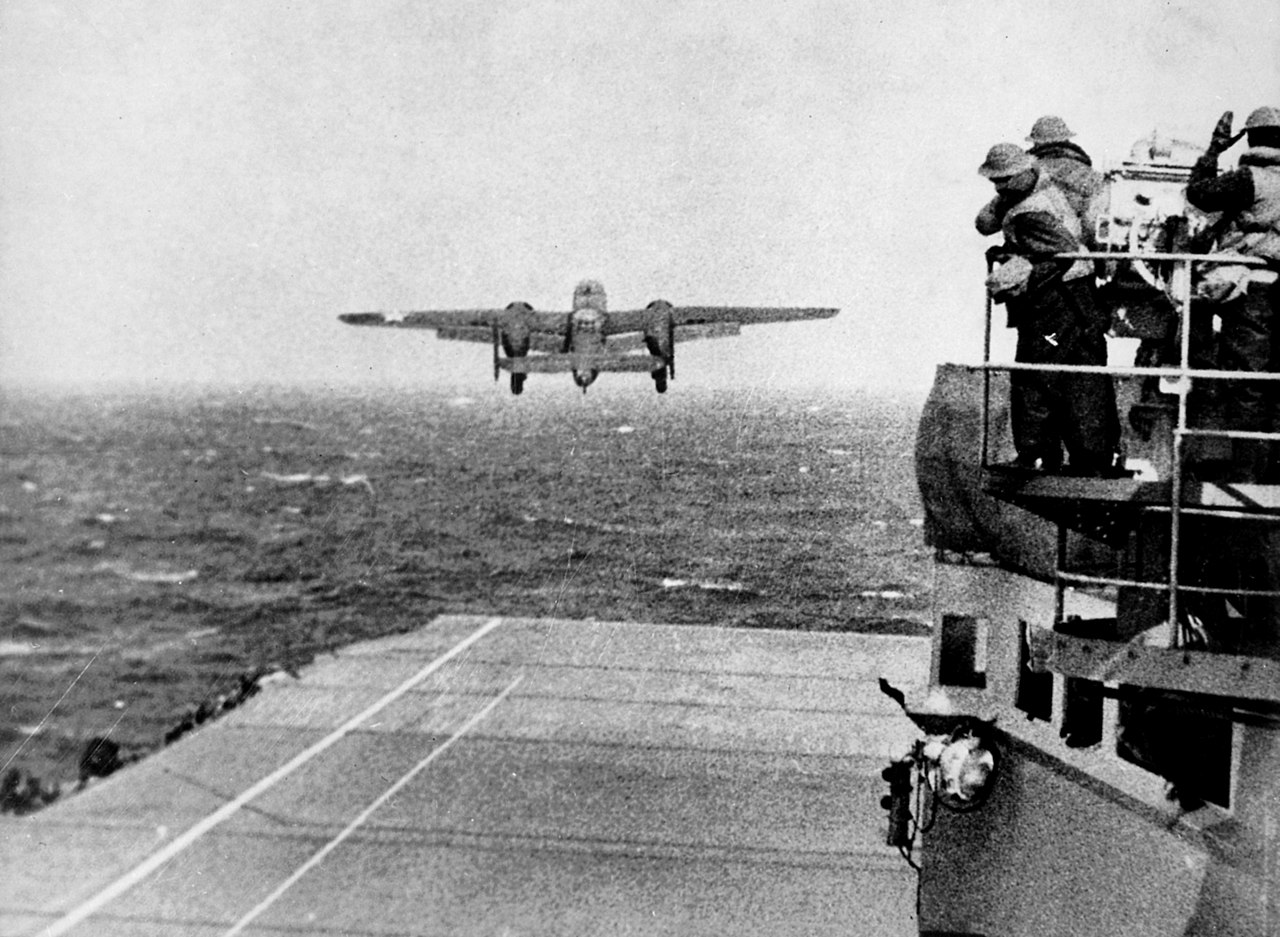

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc():format(webp)/uss-ranger-cv-4-56a61b7a5f9b58b7d0dff2d8.jpg)

:max_bytes(150000):strip_icc()/uss-ranger-cv-4-56a61b7a5f9b58b7d0dff2d8.jpg)