Energy is not just electricity. It includes the other incidental costs to production, including transportation.

Oh, boy. You opened a "can of worms" that I suspect you didn't know you were opening...The factors that play into this line of discussion are many...

- Discrete vs. process manufacturing

- Fixed and variable overhead

- Direct and indirect labor

- Direct and indirect materials

- Absorption vs variable costing

- Labor regulations

- Accounting theory, rules and practice

Frankly, I don't really want to get into the "nitty gritty" of all those considerations. That's the purview of a cost accounting class. Suffice to say that having been a CPA for 30+ years and having provided financial and business strategy, operations and financial management consulting and/or audit services for 30+ years to clients in telecom, utilities, oil, gas, mining, and high tech manufacturing, along with being part owner of a real estate development firm, I'm well aware of how energy and labor costs factor into manufacturing/construction/mining processes.

Energy is just electricity. Other forms of energy a producer may use are there and included, but they "hide" in the cost of a variety of overheads, but as the full cost of those overheads gets accounted for ,they aren't lost. They just aren't easily and specifically identifiable in terms of dollars for folks outside of a firm's accounting department. That said, those energy costs are but a part of the whole overhead cost, and they aren't necessarily or even often the bulk of overhead costs.

What makes energy noteworthy among overhead cost types -- which

isn't at all to say other overhead costs are not important for they are very important too -- is that no matter where one's factory is, one must pay for electricity, fuel, and so on. Other overhead costs, like unemployment insurance, health care, property taxes, property insurance, administrative costs, etc. may or may not exist, and they certainly vary from place to place. Thus, given that energy costs are unavoidable, no matter how great or small, they are worth considering in a firm's own "build it here or there," and occasionally in a firm's "buy it from here or there," decision making process, as well as in operational management analysis and decision making.

Energy costs are accounted for as part of the

fixed and variable overhead cost of producing goods a firm will make available for sale (GAFS). Included in the GAFS, and therefore in cost of goods sold (COGS) costs is freight-in. Freight-in includes the cost of everything needed to transport raw materials and intermediate assemblies from their source to the assembly facility. Freight-in is part of manufacturing overhead. Geneally, in B2B freight transactions, transportation providers do not list out fuel costs; they just charge for transportation -- the use of the vehicle, the fuel, the people who operate the vehicle, etc. -- as a single sum per transport event.

Overhead costs -- electricity, freight-in, and other elements -- are allocated to the per-unit cost of GAFS (GAFS becomes COGS when an item is sold). There are several methodologies for allocating the variable costs to the individual units produced. In some industries/manufacturing processes, the exact cost can be efficiently identified and assigned to specific units/batches. In other industries/manufacturing processes, the cost-benefit value proposition does not militate for specific assignment to each unit produced. For such processes, a high level approach of taking the total of variable costs and simply dividing them by the quantity of units produced in a corresponding period.

Some variable energy costs can look like fixed costs, but they aren't.

- Cost of keeping a building lit, heated/cooled, etc.are variable if the building in question is used only when production calls for it. If instead the building is used on a regular schedule and then shuts down and then resumes "functioning" again the next day, the cost becomes fixed, even though the electric bill itself may vary. The driver is whether energy use increases or decreases in accordance with production demands, not the temperature, for example.

- Cost of energy to run a given machine is variable if the machine doesn't essentially run non-stop. It's the same basic concept as above, but applied to a specific machine or array of machines used in the production process.

What determines whether a firm will account for such costs as variable or as fixed? Quite often, the way the electric company bills. If the production facilities are set up so that different elements -- building, building wings, machinery, etc. -- have distinct meters, the electric company will bill separately for each meter and the manufacturer will account for the energy cost as befits high level accounting principles such as cost-benefit, materiality, conservatism, etc., GAAP rules, industry practice, and management objectives, which include financial and managerial accounting and reporting goals and needs/requirements.

Freight-out is a selling cost not a production cost.

So with the preceding offered as a very high level perspective ("very" because

managerial/cost accounting is a discipline unto itself that accountants study for at least one semester, and even that is just enough to allow them to understand the additional theory and practice on the topic as they encounter it and need to), let's return to the original idea: the role and magnitude of energy overhead costs vs. that of

direct labor and indirect labor costs. The short is that

there is no single and reliably accurate generalization that anyone can make; however, absent the specific figures for a given company, one can make some assumptions and draw inferences and conclusions using them. Those conclusions, however, are

good only to the extent the assumptions hold true for a given firm or industry, which they generally they won't except at the very highest of levels -- national macroeconomic policy level -- that aren't very useful (or germane) for the sort of discussion we're having at the moment, but they are pf some use insofar as they can occasionally point inquiring minds in a good direction for where to look as one commences more detailed examinations.

So what can one do?

Well, to start, one has to recognize that

labor costs include direct and indirect labor and that

"indirect" and "direct" refer to how the labor is used, not whether it is or even should be (for a given industry/producer) a larger or smaller share of overall labor costs. (Indirect labor gets allocated to GAFS/COGS as overhead does.) With that in mind, one can try to get a rough sense of what some "norms" are, or one can "ballpark" estimate based on figures such as those in the document you provided in your OP.

- Compare published average hourly "rack" rates for energy use with that of labor use and assume that electricity and labor are used concurrently. This approach means that whichever costs more contributes more to GAFS cost.

- I believe the document you shared in the OP lists wage rates and energy costs by country.

Note:

Your own electricity bill shows a rate per kWH too. You pay a higher rate than do high volume energy users like factories who negotiate their rates with utility companies and who may also subsidize the cost of electricity transmission and distribution, which individual consumers do not do directly. Obviously, to the extent companies negotiate more favorable energy rates, the published averages and whatnot aren't applicable. That's the problem with published rates; every large manufacturer I've ever worked with haggles their rates down by a material amount per kWH. What's material? Well, if the factory is using hundreds of thousands or millions of kWH/year, even $0.50 is material.

- Scurry the web (or other sources) for producers who share the major component costs -- material, labor, overhead -- and tally the findings.

- Some that I found:

- Material 34%, Labor 32%, Overhead 16%, Profit 18%

- Labor 35%, Material 27%, overhead 20%, profit 18%

- 49% materials, 17% payroll, 11% overhead, 23% profit

- Materials 37%, labor 20%, overhead 20%, profit 23%

- Here's another thread from that source

- Use industry benchmarks

- Some other rationally developed method

Conclusion:

So, the short is that you are correct in that energy costs come into play as more than electricity. Where you've erred is in thinking that for most industries that something other than electricity forms the bulk of their energy costs.

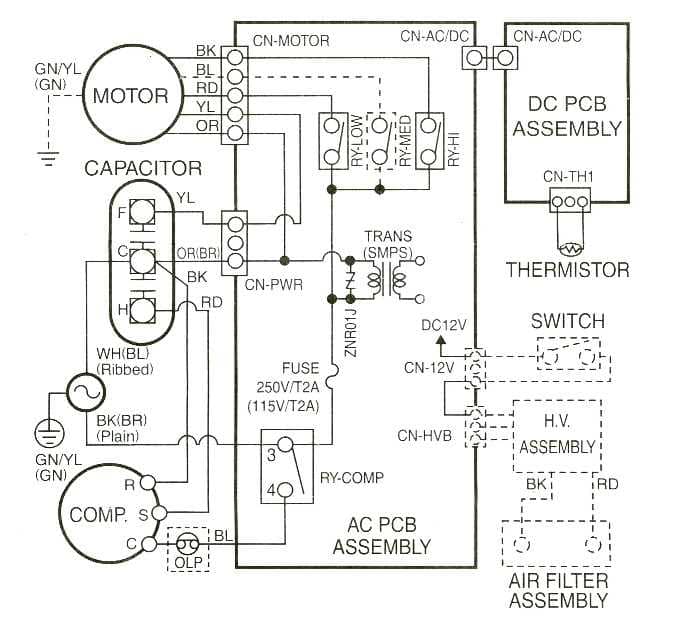

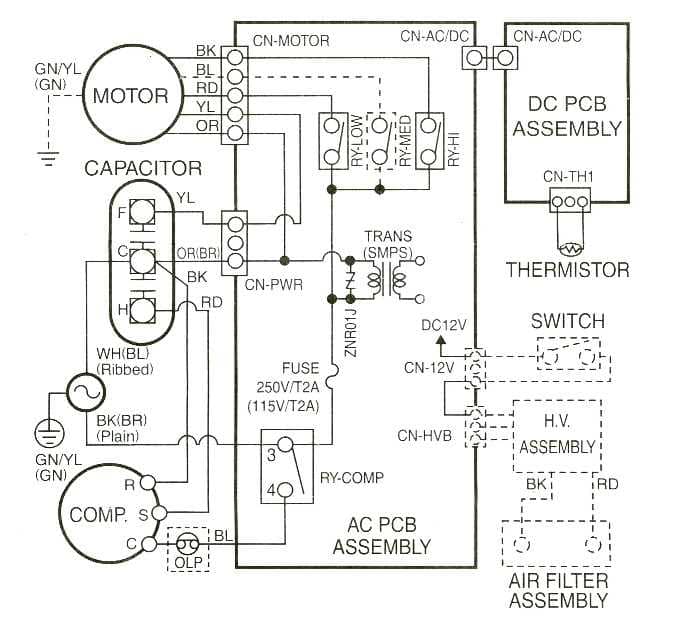

(Click image for source article: Managing Energy Costs in Manufacturing Facilities)

Hopefully, however, the preceding provides you with a better overall perspective on why "energy" cost is, for all meaningful and material extents and purposes, just electricity. Yes, there are exceptions -- both in actual usage and in cost measurement -- but unless the exceptions are universal across a whole industry (say the transportation industry, which isn't manufacturing, but it is an exception), accountants and economists will only consider electricity when they analyze energy costs. Fuel, if it needs to be considered, is treated as a separate line item from energy costs.