Hawk1981

VIP Member

- Apr 1, 2020

- 209

- 269

- 73

Chief Justice Earl Warren took his seat on the court in 1954. He had eighteen years of experience working in a district attorney's office and four years as the Attorney General of California that gave him substantial knowledge of the law in practice, but he had no experience as a judge. According to Warren's admirers, his greatest asset was his political skill in forging majorities in support of major decisions.

When Warren joined the court, it was split into two competing factions. Felix Frankfurter and Robert Jackson led one faction, which insisted upon judicial self-restraint and insisted courts should defer to the policy making prerogatives of the White House and Congress. Hugo Black and William Douglas led the other faction that agreed the court should defer to Congress in matters of economic policy, but felt the judicial agenda had been transformed from questions of property rights to those of individual liberties, and in this area courts should play a more central role.

Warren's success as a three term elected Governor of California, contributed to the leadership abilities that enabled him to guide his Court effectively. His fellow justices all stressed his forceful leadership, particularly at the conferences where cases are discussed and decided. Justice William Douglas ranked him with John Marshall and Charles Evans Hughes "as our three greatest Chief Justices."

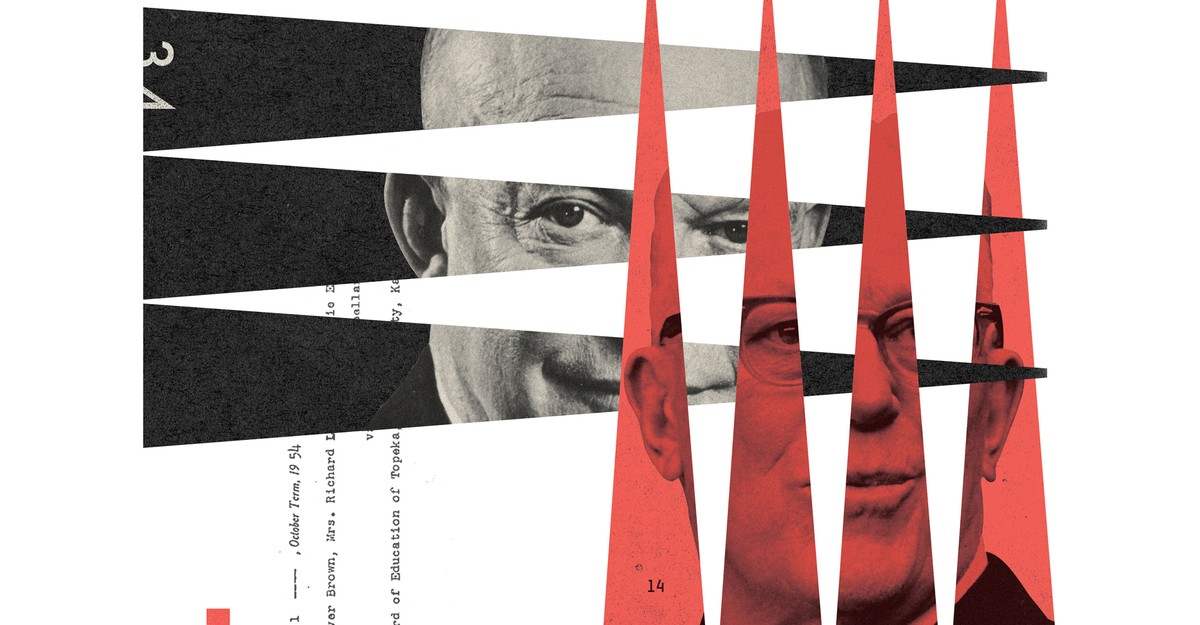

The Warren Court as it was composed from 1958 to 1962

Earl Warren and Warren Court was able to craft a long series of landmark decisions because he built a winning coalition. His leadership can best be seen in the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka decision, the most important by his Court. When the justices first discussed the case under Warren’s predecessor, they were sharply divided. But under Warren, they ruled unanimously that school segregation was unconstitutional. The unanimous decision was a direct result of Warren’s efforts. This and other Warren Court decisions furthering racial equality were the catalyst for the civil rights protests of the 1950s and 1960s and the civil rights laws passed by Congress, themselves upheld by the Warren Court.

Next in importance were the reapportionment decisions. The one man, one vote cases (Baker v. Carr and Reynolds v. Sims) of 1962–1964, had the effect of ending the over-representation of rural areas in state legislatures, as well as the under-representation of suburbs.

The Warren Court sought equality in criminal justice. The landmark case was Gideon v. Wainwright (1963), which required publicly funded counsel for indigent defendants. In Miranda v. Arizona (1966), the Court required warnings to arrested persons of their right to counsel, including appointed counsel if they could not afford one. Taking the lead in criminal justice and despite his years as a tough prosecutor, Warren always insisted that the police must play fair or the accused should go free.

Earlier Courts had stressed property rights. Under Earl Warren the emphasis shifted to personal rights, placing them in a preferred constitutional position. This was particularly true of First Amendment rights. Protection was extended to civil rights demonstrators and criticism of public officials; the power to restrain publication on obscenity grounds was also limited. In addition, the Court recognized new personal rights, notably a constitutional right of privacy.

While most Americans have generally agreed that the Court's desegregation and apportionment decisions were fair and just, disagreement about the "due process revolution" continues to this day. Applauded and criticized for using judicial power in a dramatic fashion, Warren's approach was most effective when the political institutions had defaulted on their responsibility to address problems.

Chief Justice Earl Warren and his court had a profound influence on American values. His leadership was characterized by remarkable consensus on the court, particularly in some of the most controversial cases. Journalist Anthony Lewis described Warren as "the closest thing the United States has had to a Platonic Guardian". Justice Abe Fortas described Warren's tenure as "the most profound and pervasive revolution ever achieved by substantially peaceful means."

When Warren joined the court, it was split into two competing factions. Felix Frankfurter and Robert Jackson led one faction, which insisted upon judicial self-restraint and insisted courts should defer to the policy making prerogatives of the White House and Congress. Hugo Black and William Douglas led the other faction that agreed the court should defer to Congress in matters of economic policy, but felt the judicial agenda had been transformed from questions of property rights to those of individual liberties, and in this area courts should play a more central role.

Warren's success as a three term elected Governor of California, contributed to the leadership abilities that enabled him to guide his Court effectively. His fellow justices all stressed his forceful leadership, particularly at the conferences where cases are discussed and decided. Justice William Douglas ranked him with John Marshall and Charles Evans Hughes "as our three greatest Chief Justices."

The Warren Court as it was composed from 1958 to 1962

Earl Warren and Warren Court was able to craft a long series of landmark decisions because he built a winning coalition. His leadership can best be seen in the 1954 Brown v. Board of Education of Topeka decision, the most important by his Court. When the justices first discussed the case under Warren’s predecessor, they were sharply divided. But under Warren, they ruled unanimously that school segregation was unconstitutional. The unanimous decision was a direct result of Warren’s efforts. This and other Warren Court decisions furthering racial equality were the catalyst for the civil rights protests of the 1950s and 1960s and the civil rights laws passed by Congress, themselves upheld by the Warren Court.

Next in importance were the reapportionment decisions. The one man, one vote cases (Baker v. Carr and Reynolds v. Sims) of 1962–1964, had the effect of ending the over-representation of rural areas in state legislatures, as well as the under-representation of suburbs.

The Warren Court sought equality in criminal justice. The landmark case was Gideon v. Wainwright (1963), which required publicly funded counsel for indigent defendants. In Miranda v. Arizona (1966), the Court required warnings to arrested persons of their right to counsel, including appointed counsel if they could not afford one. Taking the lead in criminal justice and despite his years as a tough prosecutor, Warren always insisted that the police must play fair or the accused should go free.

Earlier Courts had stressed property rights. Under Earl Warren the emphasis shifted to personal rights, placing them in a preferred constitutional position. This was particularly true of First Amendment rights. Protection was extended to civil rights demonstrators and criticism of public officials; the power to restrain publication on obscenity grounds was also limited. In addition, the Court recognized new personal rights, notably a constitutional right of privacy.

While most Americans have generally agreed that the Court's desegregation and apportionment decisions were fair and just, disagreement about the "due process revolution" continues to this day. Applauded and criticized for using judicial power in a dramatic fashion, Warren's approach was most effective when the political institutions had defaulted on their responsibility to address problems.

Chief Justice Earl Warren and his court had a profound influence on American values. His leadership was characterized by remarkable consensus on the court, particularly in some of the most controversial cases. Journalist Anthony Lewis described Warren as "the closest thing the United States has had to a Platonic Guardian". Justice Abe Fortas described Warren's tenure as "the most profound and pervasive revolution ever achieved by substantially peaceful means."