Mongol period

The Caliphate hastened to its end before the rising power of the

Mongol Empire. As

Bar Hebræus remarks, these Mongol tribes knew no distinction between heathens, Jews, and Christians; and their Great Khan

Kublai Khan showed himself just toward the Jews who served in his army, as reported by

Marco Polo.

Hulagu (a Buddhist), the destroyer of the Caliphate (1258) and the conqueror of Palestine (1260), was tolerant toward Muslims, Jews and Christians; but there can be no doubt that in those days of terrible warfare the Jews must have suffered much with others. Under the Mongolian rulers, the priests of all religions were exempt from the poll-tax. Hulagu's second son,

Aḥmed, embraced Islam, but his successor,

Arghun (1284–91), hated the Muslims and was friendly to Jews and Christians; his chief counselor was a Jew,

Sa'ad al-Dawla, a physician of Baghdad.

It proved a false dawn. The power of Sa’ad al-Dawla was so vexatious to the Muslim population the churchman

Bar Hebraeus wrote so “were the Muslims reduced to having a Jew in the place of honor.”

[24] This was exacerbated by Sa’d al-Dawla, who ordered no Muslim be employed by the official bureaucracy. He was also known as a fearsome tax collection and rumours swirled he was planning to create a new religion of which Arghun was supposed to be the prophet. Sa’d al-Dawla was murdered two days before the death of his Arghun, then stricken by illness, by his enemies in court.

After the death of the great khan and the murder of his Jewish favorite, the Muslims fell upon the Jews, and Baghdad witnessed a regular battle between them.

Gaykhatu also had a Jewish minister of finance,

Reshid al-Dawla. The khan

Ghazan also became a Muslim, and made the Jews second class citizens. The Egyptian sultan Naṣr, who also ruled over Iraq, reestablished the same law in 1330, and saddled it with new limitations. During this period attacks on Jews greatly increased. The situation grew dire for the Jewish community as Muslim chronicler Abbas al-’Azzawi recorded:

“These events which befell the Jews after they had attained a high standing in the state caused them to lower their voices. [Since then] we have not heard from them anything worthy of recording because they were prevented from participation in its government and politics. They were neglected and their voice was only heard [again] after a long time.”

[24]

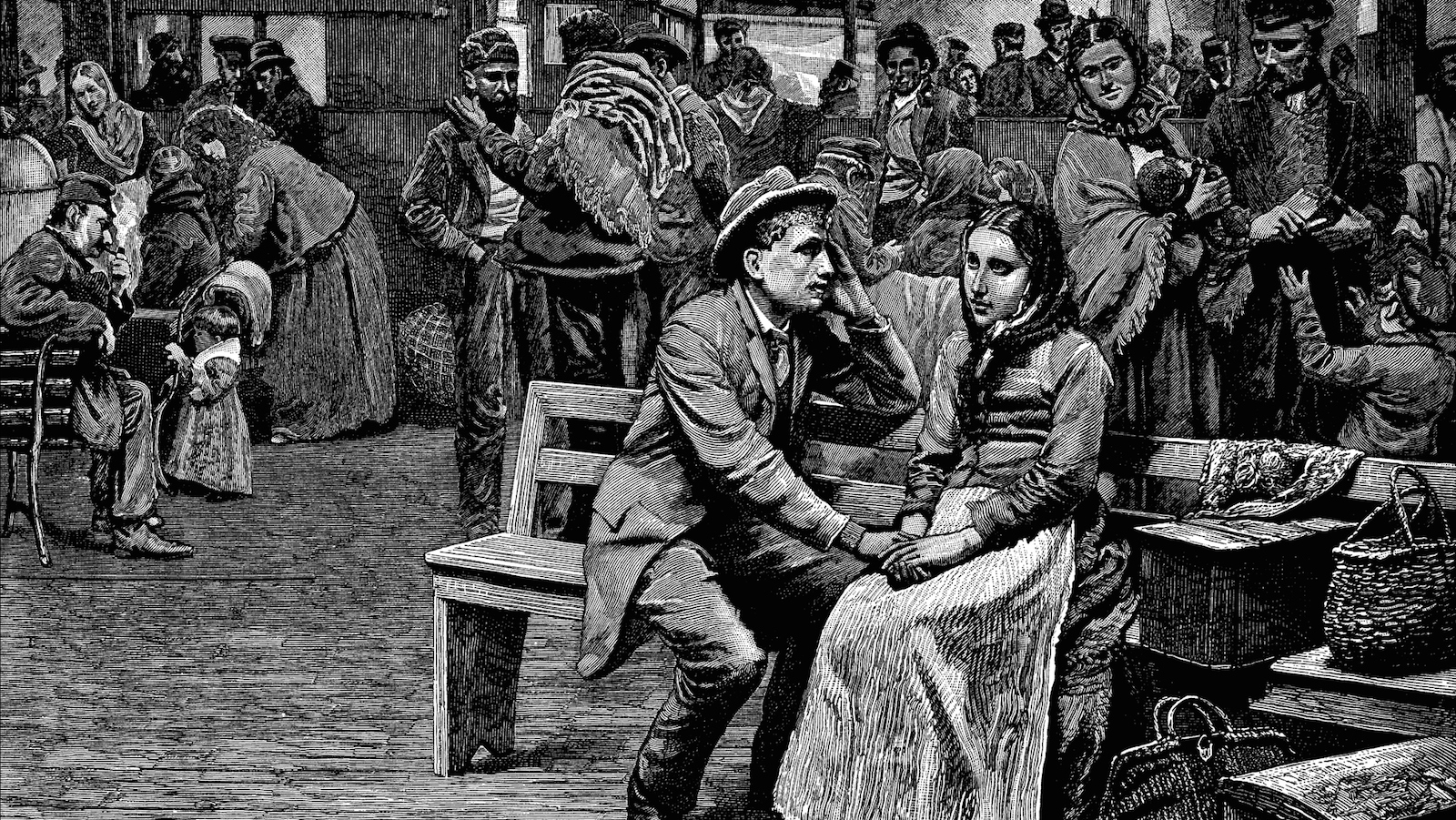

Baghdad, reduced in importance, ravaged by wars and invasions, was eclipsed as the commercial and political centre of the Arab world. The Jewish community, shuttered out of political life, were reduced too and the status of the

Exilarch and the Rabbis of the city diminished. Great numbers of Jews began to depart, seeking tranquility elsewhere in the Middle East beyond a now troubled frontier.

[24]

Mongolian fury once again devastated the localities inhabited by Jews, when, in 1393,

Timur captured Baghdad,

Wasit,

Hilla,

Basra, and

Tikrit, after obstinate resistance. Many Jews who had fled to Baghdad were slaughtered. Others escaped the city to Kurdistan and Syria. Many were not so fortunate, with one report mentioning 10,000 Jews killed in Mosul, Basra, and Husun Kifa.

The ruins of Baghdad after Timur's conquests was described in 1437 by the Muslim chronicler

Al-Maqrizi: “Baghdad is in ruins. It has no mosque, no congregation of believers, no call to prayer and no markets. Most of the date palms have withered. Most of the irrigation canals are blocked. It cannot be called a city.”

[24]

After the death of

Timur, the region fell into the hands of marauding

Turkmen tribesmen who were unable to establish a government of any kind. Ravaged by conquest,

Iraq fell into lawlessness and became close to uninhabitable. Roads became dangerous and

irrigation systems collapsed, seeing precious farmland in the delta region sink below water. Rapacious

Bedouin filled the vacuum, rendering the caravan trade all but impossible. Denied authority of any kind and severed from its historic trading ties with the

Middle East and the

Far East, the ancient city of Baghdad had become a minor town.

[24]

The cumulative effect of the Mongol rampage and the social collapse that followed was that of the pre-existing Jewish community of Baghdad either died or fled. Jewish life entered a Dark Age. According to historian Zvi Yehuda, the fifteenth century sees no reports on Jews in Baghdad or in its surroundings, in Basra, Hilla, Kifil, ‘Ana, Kurdistan, even in Persia and the Persian Gulf.

[24] The organized Jewish community of Iraq appears to have disappeared in this period for more than four generations.

This is behind the discontinuity between the present traditions of Iraqi Jewry and the Babylonian traditions of

Talmudic or

Geonic times.

[25] It remains the case that most Jewish Iraqis are of indigenous Middle Eastern ancestry rather than migrants from Spain, as in the case of parts of North Africa and the Levant.

en.m.wikipedia.org