While it may not matter who benefits most or least to those studying macro economics, to those tens of thousands who no longer have a job as good as they once had, a job that afforded them a lifestyle they enjoyed, it matters to them.

I have, just as have economic researchers, acknowledged this.

How many economists, lawyers, accountants and upper level management types do you know who lost their jobs to free trade agreements?

How many I know or don't know is irrelevant.

- I don't know anyone who's lost their job due to offshoring, yet there are folks who have.

- I know and know of folks who've lost their job due to technology implementations in organizations that didn't offshore anything, but even knowing (of) them doesn't have a thing to do with whether they experienced a job loss.

- I also know of administrative folks (mid to lower level) who've lost their jobs due to multinational corporations offshoring their "back office" (accounting (note: everyone in a company's accounting department is not an accountant, in fact, few of those folks are; most are bookkeepers, which is not the same thing as being an accountant), finance operations to lower labor cost areas. In some of those relocations, some people didn't lose their jobs because they opted instead to move to the new location, but had they not made that choice, they would have lost their job.

- The people whom I know who are accountants, attorneys, business managers, and so on also are business owners or on a career track to become owners. Thus, unless they screw up in a big way, they are and will remain in control of their career prospects.

- Not related but hopefully insightful: Part of the reason I am an international consultant is that years ago I could tell that at some point (I didn't know precisely when), the work I do wouldn't eventually be sought at the billing rate I demand because the industry/service area will by then have matured. Thus I began to develop myself for delivering my services to non-U.S. organizations. That's what I do now because that's where the growth is for what I do. Of course, I directly manage a large project in the U.S. once in a while, but in the past decade, ~80% of my projects have had nothing to do with the domestic units of U.S. corporations.

Were I to have insisted on working exclusively in the U.S., I'd have had to evolve my skills or diversify them to do so. Quite simply, I didn't want to, so I instead directed my career to where what I wanted to do remains in demand. It's Marketing 101; it's just that I, as does everyone else, had to apply the lessons of marketing to the "thing" I'm marketing, which is myself, my labor. That's no different than what everyone must do, and like everyone else, I have to plan ahead and choose where to direct my career on an ongoing basis. This sort of thing isn't static; what one does now that works isn't guaranteed to be the right choice later.

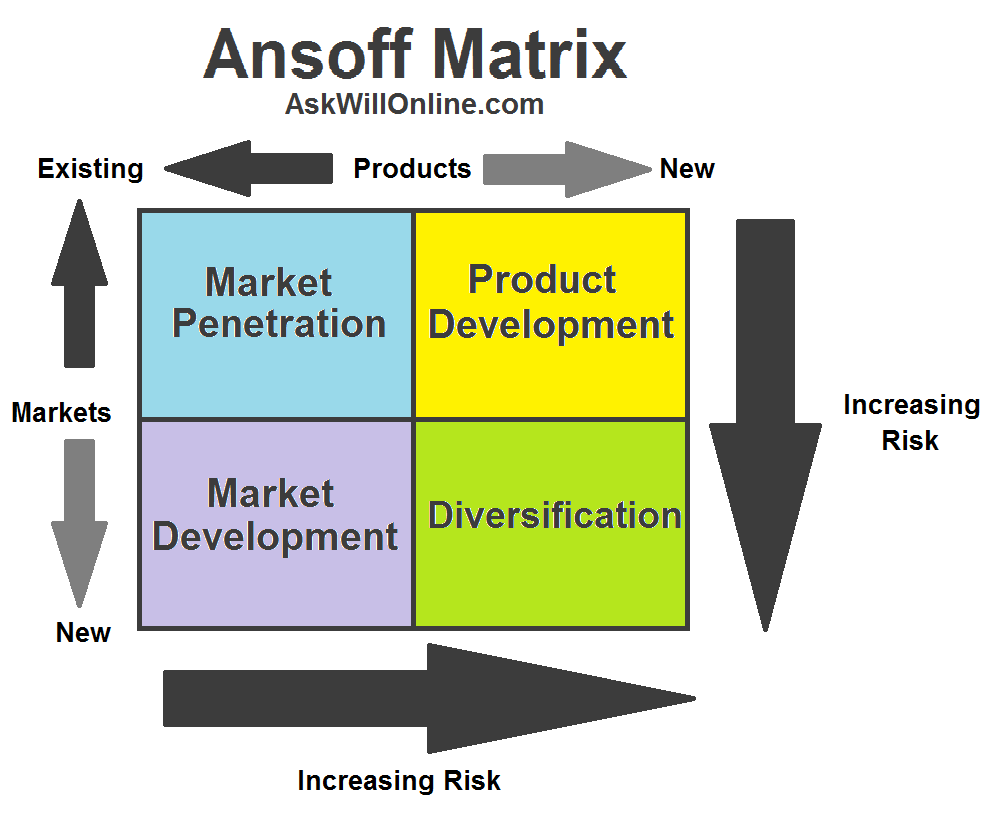

It's worth noting that of the four strategic options shown in the image above, all four of them of them may or may not be available at all times, but at least one of them will always be available and executable. Whether one will be effective implementing any of the given strategies depends on the tactical approach one uses to do so.

FWIW, I've looked for credible figures that identify the nature and extent of management and professional services job losses that are attributable to NAFTA specifically and free trade in general. The closest I've come by is in the report from the CRS that I cited earlier, but even it doesn't expressly address management/professional services jobs gained or lost due to NAFTA. Perhaps nobody gives a damn about those workers?

A couple (but not sole) critical traits distinguish management/professional services jobs from those typically thought of as "manufacturing jobs,"

- They, along with highly skilled physical labor roles, are jobs that align with the U.S.' comparative advantage. (Theory of comparative advantage.)

- Our Comparative Advantage

During the early stages of the development of a new technology, the United States has a comparative advantage in the production of the products enabled by this innovation. However, once these technologies become well-understood and production processes are designed that can make use of less-skilled labor, production will migrate to countries with less expensive labor.

These economic forces are not substantially different from the economic forces that lead to most children’s toys being developed in the United States and mass-produced in China and other developing countries. Once the production process for a product can be standardized to such an extent that there are potential producers around the world, global competition will drive production to lowest cost country, and thereby benefit all consumers of these products.

- What Ideas Are Worth: The Value of Intellectual Capital And Intangible Assets in the American Economy

As the world’s most advanced economy, the United States and its multinational companies use their intellectual capital and intangible assets to create comparative advantages in global markets. Therefore, many industries which are highly idea-intensive, measured by intellectual capital and intangible assets, occupy prominent positions in U.S. exports. Pharmaceuticals and medicines, for example, were the third largest class of U.S. exports in 2009, exceeded only by semiconductors and aerospace products and parts.

- Has US Comparative Advantage Changed?

[I can't copy and paste passages from this document. The author's aim is to analyze and discuss the implications of the shift in U.S. comparative advantage -- from all levels/forms of production (skilled and unskilled) and intellectual services to that of skilled production and intellectual services -- on the sustainability of deficits. That said, the point I'm making here is nonetheless discussed and established in the process of making the author's points about the sustainability of deficits.]

- People with these jobs are "knowledge workers." Thier jobs are those one obtains and keeps based on intellectual capital and almost no physical ability rather than based on physical ability and some intellectual capital. Intellectual capital is a composite comprising human capital, structural or organizational capital and relationship capital. Human capital, as intellectual capital component, includes individual capabilities, knowledge, skills, expertise and experience of employees and managers in a company. Knowledge, in this context, implies knowledge relevant for problem solving, as well as capability to constantly upgrade one's "tank" of knowledge and skills acquired on the basis of learning and experience.

What makes management/professional services jobs different is that the intellectual capital holders of them develop can be taken and applied at any company. Thus, the manufacturing industry accountants and managers who may have lost their jobs when a large factory moved offshore can nonetheless use their skills at another company. Accordingly, if they don't find a comparable new job in the aftermath of an offshoring, it's more likely because they don't want to (don't want to find a comparable job, or don't want to do "something" that accepting that comparable new job entails) than it is that they just can't get a comparable new job.

What does all that mean for displaced physical labor workers? It means that they need to "get with the program," that is, transform themselves and become "knowledge workers." Of course, for many such workers, that means getting new training, not griping about the fact that there aren't "good" manufacturing jobs.

Realizing this, I favored Bernie Sanders and his "free college/trade school" policy. Quite simply, the unskilled labor manufacturing jobs some people want aren't coming back, and all the lamentations in the world won't motivate companies to return their factory operations to the U.S. until U.S. workers get paid materially less than laborers outside the U.S.

Barring one's willingness to obtain that training (and/or support policies/policy makers that make it available to them at very low or no cost and then obtaining it) and transform oneself into a different kind of worker -- accountant, manager, lawyer, welder, petroleum production worker, product designer, project manager, software developer, nurse, etc. -- one has a few choices that are exactly what's depicted in the Ansoff Matrix shown above:

- Take whatever job one can get and quit hoping for a job that's not going to exist in the U.S.

- Rely on the kindness of others and quit hoping for a job that's not going to exist in the U.S.

- Move to a place that has a comparative advantage in performing unskilled labor, along with a lower cost of living, and be middle class in that locality. Coming from the U.S., one will have a distinct advantage over the existing locals due to one's prior experience.

I know a lot of folks think that's a terrible proposition, but I suspect many folks who feel that way also have never been anywhere outside the U.S. and seen what a middle class lifestyle is like in those countries. Go to Mexico, China, India, Argentina, a Central American country, or other countries with a greatly expanding middle class, and check it out. Believe it or not, middle class lifestyles in those places are very much like one in the U.S., it just doesn't take as much money to live that way in those places.

There's a reason it's said of NYC that if one can make it there one can make it anywhere. It's so damned expensive in NYC that the only way to make it is to do something that pays highly. Well, that's also true of the U.S. vs. other countries. If what one does or is willing to do doesn't pay well enough to support a U.S. middle class existence, then moving to a place where what one does/will do can support a middle class existence is the rational choice to make.

Honda doesn't come close to needing the amount of workers GM used to need.

I presume you are referring to the related auto parts/components producers such as Dayton's Delphi. I don't know if they do or do not, and you've provided no references that corroborate your assertion. I quickly looked to see if I could find any that do. Here is what I found:

- http://www.fisherhonda.com/honda-ac...cars-with-the-most-north-american-made-parts/

According to Honda, “94 percent of Honda and Acura vehicles sold in the U.S. in 2013 were manufactured in North America, the highest percentage of any international automaker.” On top of that, 70 percent of the Honda Accord’s content is sourced from the U.S. and Canada. Fifteen percent is sourced from Japan. It is not stated where the other 15 percent of content is from. The Civic is comprised of 65 percent of content that is from the U.S. and Canada. Between 15 and 20 percent is also sourced from Japan. The additional origin of the remaining 15 to 20 percent wasn’t reported. Here’s a look at the Accord, Civic, and Honda’s assembly plants.

- HONDA MOTOR CO LTD 20-F

Honda manufactures the major components and parts used in its products, including engines, frames and transmissions. Other components and parts, such as shock absorbers, electrical equipment and tires, are purchased from numerous suppliers. The principal raw materials used by Honda are steel plate, aluminum, special steels, steel tubes, paints, plastics and zinc, which are purchased from several suppliers. The most important raw material purchased is steel plate, accounting for approximately 45% of Honda’s total purchases of raw materials.

A few notes:

- I'm not opposed to accepting the assertion you made is true, for it'd merely be a fact, and facts are what they are. I am opposed to accepting the assertion you made is true solely on the basis that you said it, which is all I have right now for accepting it.

- Regardless of how close Honda comes to needed the quantity of workers GM once did, it's also true that given GM's having closed down Olds and Pontiac, GM also doesn't come close to needing the quantity of workers it once did. Even were GM to make 100% of every car it sells in the U.S., it still would not need as many workers as it formerly did due in large part to production automation.

Production automation is very important in any discussion about manufacturing jobs lost. It's not as though companies like GM and others went from building their goods using U.S. workers only and then went abroad and continued to use human labor to do the same tasks. What they did, wherever possible, was implement production automation and optimization technologies and use lower cost labor where

your data driven analysis seems void of the feeling of personal loss experienced by hundreds of thousands of our fellow citizens.

Of course the actual situational analysis i've presented is devoid of that emotional component; it wouldn't be objective analysis were it not absent the emotional bias you suggest. My sympathy for those folks' situation is found among the solution options I have suggested. Specifically, I would not be supportive of Mr. Sanders' "free education/training" initiative were I not sympathetic to people's need to have good jobs, the nation's need for people to have good jobs, and the fact that unemployed unskilled workers need to evolve their skillsets to include aptitudes that are in demand in the U.S.

The road to overall emotional satisfaction is paved with loads of objective analysis and decision making. One aspect of that analysis requires one to consider oneself in terms of basic economics. One is a supplier of something, one's labor. People are generally capable of performing a variety of types of labor. To maximize one's profits (wage), one should provide a type of labor that is highly demanded. Sure, one could provide a commodity form of labor that is indistinguishable from that which everyone else can provide, but doing something that some others, but not all others, can provide pays a lot better.

(Remember that with commodities, the name of the game is "provide more of the commodity where it's demanded." Well, an individual can only perform "so much" work in a day, and however much that be, it's not appreciably more than can any other individual. Even the best "widget assembler" in the country doesn't earn materially more than the worst one; they both are struggling to make ends meet. Thus if one wants to be profitable selling commodity labor, one should open a temp/staffing agency or recruitment firm.)

So, when considering what one will for work, and when I write about viable and effective solution approaches for folks who seek (better) jobs, yes, I do so without the "emotional baggage." There's a time and place for that "baggage," but in the process of evaluating how to resolve the problem of being under/unemployed is neither the time nor the place. That problem solving process is best performed not by considering what one (another) likes and wants, but rather by (1) identifying the actual facts of the situation (not wasting time arguing over whether they are facts or wishing they were not or thinking the should not be the facts), (2) considering what options exist to overcome the problem, (3) determining how long it takes to realize results from each option, (4) figuring out how long one can wait given one's specific needs, and (5) choosing the one that will achieve the required goal in the shortest amount of time that one has available to wait for those goals to happen.

I am quite capable of being sympathetic to others' circumstances and that they find themselves in them. I have no emotional leanings, however, when it comes to finding and implementing solutions to the problem. Nearly all of what you've seen me write about has to do with the latter. Where do folks observe and experience my more sympathetic side? I'll let you guess...I've also discussed that too, and I think you've read enough of my posts to know the answer.

you make every effort to educate us masses as to how good we have it because of free trade.

There's no question that a number of my posts are didactic; however, the purpose and themes of them aren't to inform folks of "how good we have it because of free trade." One purpose as goes my discussions about free trade is to highlight that the conclusion that free trade is the sole or dominant cause of the problem is mistaken. I won't deny that free trade (NAFTA in particular) has had an impact, but, as the

rigorously developed reference original research materials I constantly present show, free trade (NAFTA) are a minor contributor.

For those who have witnessed the devastation brought on by shipping large numbers of good paying jobs out of the country, skepticism will abound.

Yes it will. That skepticism is substantively useless in any individual's quest to overcome their problem. Sure, they can find sources that will palliate their ire and disdain for free trade. The central point I've been making is that their anger is misplaced.

- Folks who "get over" whether free trade is the cause or whether something else is, i.e, ignore their skepticism, and instead endeavor to do what they must to "make it" in the world that is "now," they will find a happy place in the current economy. Once they are in that place, then they can consider whether free trade was the main cause for why they once were not in that happy place.

So the next time you encounter a skeptic of sorts. Ask them this:

- Do you have a good job? If they do, ask them why they think what they think given the wealth of objective and rigorous research that shows they are mistaken. Ask them why they insist on accepting the conclusions drawn by various partisan groups instead of reading the original research that has been "cherry picked" to make a point. Their having a good job means they don't have to work all the time and eat and sleep the rest of the time. Accordingly, they have the time to read original scholarly research instead of reading Breitbart, listening to Fox/MSNBC, or whatever other distiller of original research that captures their fancy.

- What is is "Joe Displaced Worker" supposed to do right now to begin altering his situation? Ask them that because the fact is that "Joe" doesn't have time to wait for Mrs. Clinton, Trump or any other politician or political process to make his life better. The U.S. is a democratic republic, not a monarchy, benevolent dictatorship or papacy. The folks in power simply cannot effect change in six months or less, but on his own and acting with deliberacy, "Joe" can initiate effecting the changes he must make happen for himself. No, short of buying a winning lottery ticket, "Joe" won't achieve "overnight" results, but neither will elected officials, most especially given that for the next three months, the primary thing elected folks are focused on is getting reelected, and they'll have that same focus for another three months, two years from now.