Drug-resistant food poisoning is now in the US - AOL.com

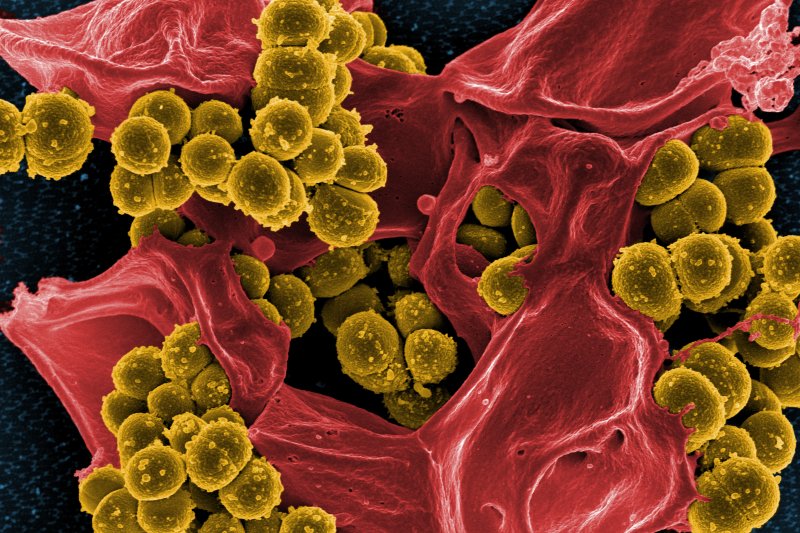

Food poisoning bug making the rounds. Looks like a nasty one cuz it fights off the drug to kill it.

Food poisoning bug making the rounds. Looks like a nasty one cuz it fights off the drug to kill it.