- Mar 11, 2015

- 100,859

- 108,250

- 3,645

There are several foreign members in this forum, sadly some of them are trump supporters. But in reality there is an entire world out there and we live with everybody else. And everybody else doesn't seem to think Trump is the answer.

In early april, a crowd of diplomats and dignitaries gathered in the Flemish countryside to toast the most powerful military alliance in the history of the world, and convince themselves it wasn’t about to collapse.

They arrived in a convoy of town cars that snaked down a private driveway and deposited them outside Truman Hall, a white-brick house set on 27 acres of gardens and hazelnut groves. Originally built by a Belgian chocolatier, the estate was sold to the American government at a discount—a thank-you gift for liberating Europe—and became the residence of the U.S. ambassador to NATO. Tonight, Julianne Smith, the inexhaustibly cheerful diplomat who currently holds the job, was stationed at the front door, greeting each guest.

At Truman Hall, every effort was made to keep the mood festive despite a storm looming outside. Beneath a backyard tent, Secretary of State Antony Blinken spoke, followed by NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg.

Stoltenberg, lean and unrumpled, decided to do something diplomatically unorthodox: acknowledge reality. Anxiety about America’s commitment to the alliance had been omnipresent and unspoken; now Stoltenberg was directly addressing the dangers of a potential U.S. withdrawal from the world.

“The United States left Europe after the First World War,” he said, adding, with a measure of Scandinavian understatement, “That was not a big success.”

The wind was picking up outside, pounding the flaps of the tent and making it difficult to hear. Stoltenberg raised his voice. “Ever since the alliance was established,” he said, “it has been a great success, preserving peace, preventing war, and enabling economic prosperity—”

A strong gust hit the tent, rattling the light trusses above. Guests glanced around nervously.

The undercurrent of dread at Truman Hall was not unique. I encountered it in nearly every conversation I had while traveling through Europe this spring. In capitals across the continent—from Brussels to Berlin, Warsaw to Tallinn—leaders and diplomats expressed a sense of alarm bordering on panic at the prospect of Donald Trump’s reelection.

“The anxiety is massive,” Victoria Nuland, who served until recently as undersecretary for political affairs at the State Department, told me. Like other diplomats in the Biden administration, she has spent the three-plus years since Trump unwillingly left office working to restabilize America’s relationship with its allies.

“Foreign counterparts would say it to me straight up,” Nuland recalled. “‘The first Trump election—maybe people didn’t understand who he was, or it was an accident. A second election of Trump? We’ll never trust you again.’”

www.theatlantic.com

www.theatlantic.com

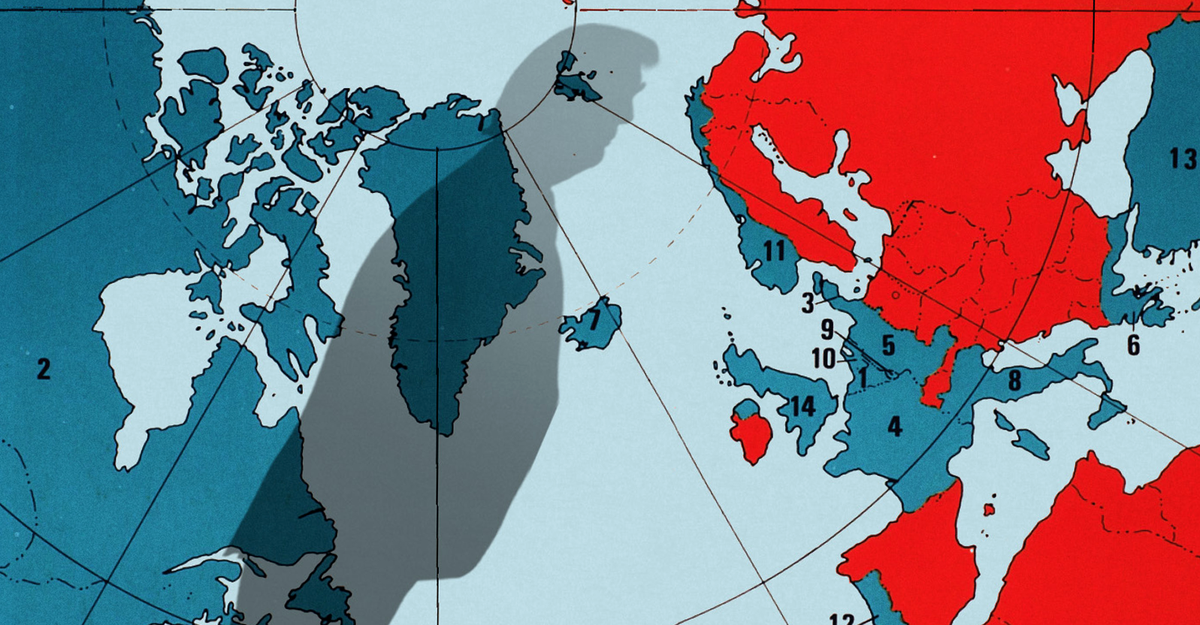

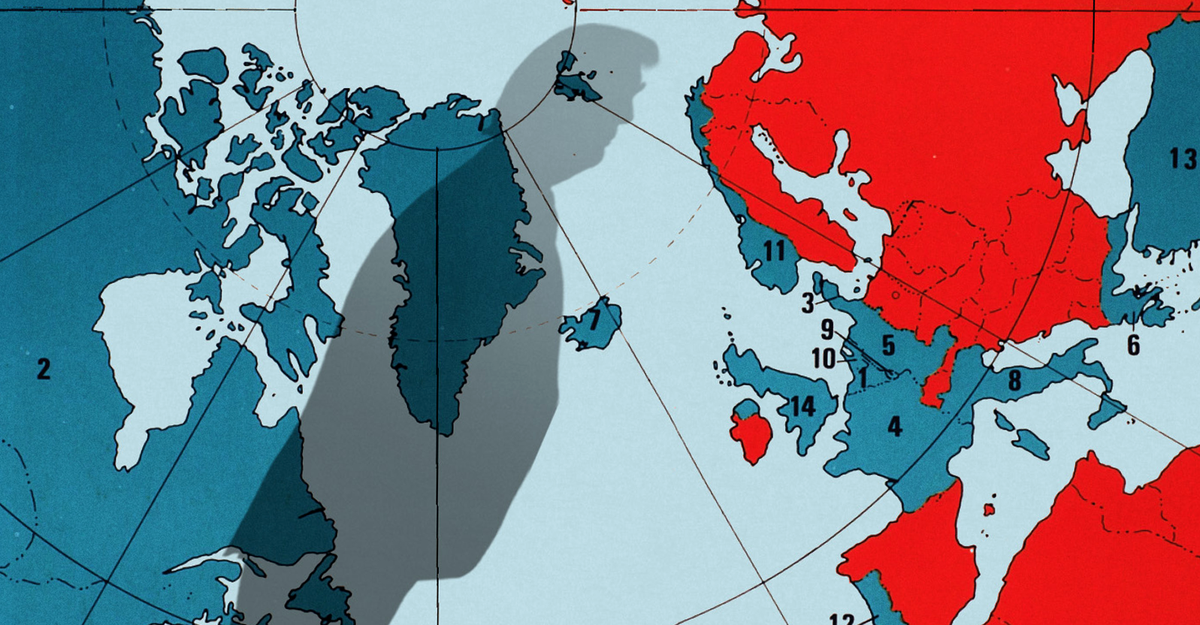

WHAT EUROPE FEARS

American allies see a second Trump term as all but inevitable. “The anxiety is massive.”In early april, a crowd of diplomats and dignitaries gathered in the Flemish countryside to toast the most powerful military alliance in the history of the world, and convince themselves it wasn’t about to collapse.

They arrived in a convoy of town cars that snaked down a private driveway and deposited them outside Truman Hall, a white-brick house set on 27 acres of gardens and hazelnut groves. Originally built by a Belgian chocolatier, the estate was sold to the American government at a discount—a thank-you gift for liberating Europe—and became the residence of the U.S. ambassador to NATO. Tonight, Julianne Smith, the inexhaustibly cheerful diplomat who currently holds the job, was stationed at the front door, greeting each guest.

At Truman Hall, every effort was made to keep the mood festive despite a storm looming outside. Beneath a backyard tent, Secretary of State Antony Blinken spoke, followed by NATO Secretary-General Jens Stoltenberg.

Stoltenberg, lean and unrumpled, decided to do something diplomatically unorthodox: acknowledge reality. Anxiety about America’s commitment to the alliance had been omnipresent and unspoken; now Stoltenberg was directly addressing the dangers of a potential U.S. withdrawal from the world.

“The United States left Europe after the First World War,” he said, adding, with a measure of Scandinavian understatement, “That was not a big success.”

The wind was picking up outside, pounding the flaps of the tent and making it difficult to hear. Stoltenberg raised his voice. “Ever since the alliance was established,” he said, “it has been a great success, preserving peace, preventing war, and enabling economic prosperity—”

A strong gust hit the tent, rattling the light trusses above. Guests glanced around nervously.

The undercurrent of dread at Truman Hall was not unique. I encountered it in nearly every conversation I had while traveling through Europe this spring. In capitals across the continent—from Brussels to Berlin, Warsaw to Tallinn—leaders and diplomats expressed a sense of alarm bordering on panic at the prospect of Donald Trump’s reelection.

“The anxiety is massive,” Victoria Nuland, who served until recently as undersecretary for political affairs at the State Department, told me. Like other diplomats in the Biden administration, she has spent the three-plus years since Trump unwillingly left office working to restabilize America’s relationship with its allies.

“Foreign counterparts would say it to me straight up,” Nuland recalled. “‘The first Trump election—maybe people didn’t understand who he was, or it was an accident. A second election of Trump? We’ll never trust you again.’”

What Europe Fears

American allies see a second Trump term as all but inevitable. “The anxiety is massive.”