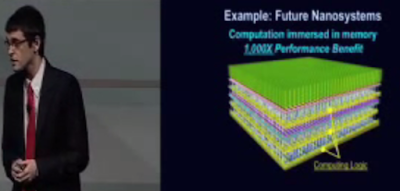

A new method of designing and building computer chips could lead to blisteringly quick processing at least 1,000 times faster than the best existing chips are capable of, researchers say.

The new method, which relies on materials called carbon nanotubes, allows scientists to build the chip in three dimensions.

The

3D design enables scientists to interweave memory, which stores data, and the number-crunching processors in the same tiny space, said Max Shulaker, one of the designers of the chip, and a doctoral candidate in electrical engineering at Stanford University in California.

Reducing the distance between the two elements can dramatically reduce the time computers take to do their work, Shulaker said Sept. 10 here at the "Wait, What?" technology forum hosted by the Defense Advanced Research Projects Agency, the research wing of the U.S. military.

Progress slowing

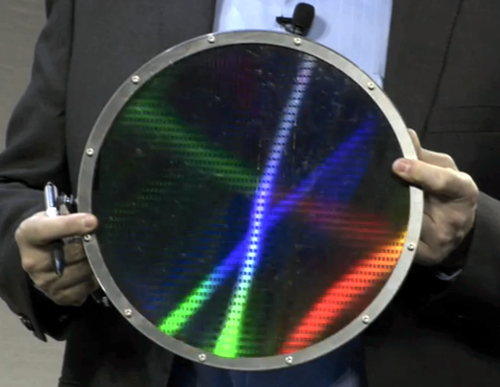

The inexorable advance in computing power over the past 50 years is largely thanks to the ability to make increasingly smaller silicon

transistors, the three-pronged electrical switches that do the logical operations for computers.

According to

Moore's law, a rough rule first articulated by semiconductor researcher Gordon E. Moore in 1965, the number of transistors on a given silicon chip would roughly double every two years. True to his predictions, transistors have gotten ever tinier, with the teensiest portions measuring just 5 nanometers, and the smallest functional ones having features just 7 nanometers in size. (For comparison, an average strand of human hair is about 100,000 nanometers wide.)

The decrease in size, however, means that the

quantum effects of particles at that scale could disrupt their functioning. Therefore, it's likely that Moore's law will be coming to an end within the next 10 years, experts say. Beyond that, shrinking transistors to the bitter end may not do much to make computers faster.