For the truth? Watch this whole video....IT's a long watch, but it is necessary. They don't teach it in high school, college, or cover it in documentaries in the MSM.

I watched the long version video early this morning.....

MisterBeale, you are correct that the (long) video is excellent -- well, very good, excellent is too strong -- and well worth watching. The short one is good, but really doesn't say much that's critical to the topic of illegal immigrants.

Folks who are willing to consider the essay and its key points in totality -- rather than compartmentalizing bits and pieces of it and then transforming those isolated bits into the "be all end all" for advancing a partisan stance on a single issue -- will find much of value there.

The author of the two videos Mr. Beale posted, Stefan Molyneux, is, for the most part, spot on right. The short video essay doesn't say much of note that relates to immigration, which is the subject of the thread. The long one does have some interesting observations/analysis that draws a correlation between Roman slavery/slaves and immigration/immigrants. The correspondence he makes, though reasonable at a high level, leaves something to be desired in one important dimension.

Mr. Beale is not correct that "they don't teach" that stuff in high school or college. [1] It would, however, be correct to say that the content isn't frequently (perhaps not at all) presented as a unified set of ideas in one single class that one might take at baccalaureate or lower levels. That it isn't is unsurprising.

- Baccalaureate level expectation -- develop strong understanding of the most important bits of foundational knowledge in a discipline and focus on doing the same for a tiny "corner" of the disciple.

- Master's level expectation -- develop strong understanding of the general body of knowledge across the entirety of a discipline and integrate those ideas with facts from related disciplines. (This is what Stefan's long video does.)

- Doctoral level expectation -- contribute to the body of knowledge in a given discipline by performing original research and sharing it.

Given that's the way, it's not surprising that folks who've not taken some political/governance science along with taking (1) a master's degree in history with a concentration on economics, or (2) an econ master's with focus on Roman/Greek economic history, or (3) a baccalaureate or high school class that called one to consider the economics of the Roman Empire (most likely for a paper), the integrated whole that Molyneux presents isn't likely to come up.

That's not without good reason. One has to have a strong understanding of macro and micro econ (principles-level class is sufficient) and a whole lot of detail about Roman history, detail that, at high school and bachelor's levels, is beyond the scope of anything but a class devoted to Rome's history. It's not the econ or poly-sci that inhibits students making the observations and arriving at the conclusions Stefan shares; it's the history. I don't think many people would be keen to have their high school age kids exposed to the nature and extent of Roman depravity and decadence such a course will necessarily introduce. Even considering my own very bright and mature kids, I don't think at high school age they were ready to learn of that history and keep it in the right context.

Should it? Well, that's a normative decision. I could easily say it should, but I like economics and history.

Specific Observations:

- Stefan has some inconsistencies and contextual missteps. I don't think they're material to the overall comparison he makes in the essay, but they are clearly contradictions.

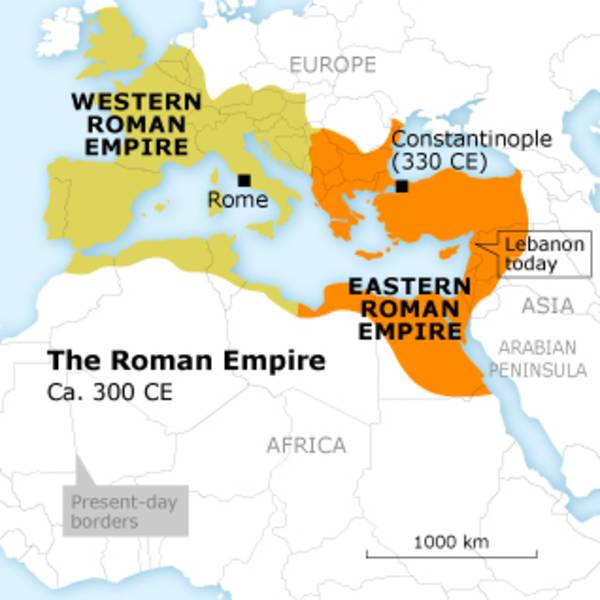

- Early in the essay, Stefan notes that Goths and Germans sought to join the Empire to partake of the riches of the Empire. He doesn't present that as an ignoble desire on their part, but rather as a rational one. He goes on, then, to describe how those would be immigrants don't assimilate well into the culture, because economics not cultural mores drew them in. He classifies the presences of so many economically motivated immigrants as part of what contributed to the decline of the Empire. Later, in his discussion of the declining years of the 5th century, he describes the very same categories of people as having noble ideas and intentions, and blames Roman Tyranny and coarseness for what he earlier attributed to immigrants. He never establishes or even hints that earlier (in the age of the Republic and early Empire years) immigrants were the impetus for the later Emperors' governance failings. He doesn't, of course, because they were not.

- At one point Stefan cites excise taxes as being bad fiscal policy for the people, citing farmers in particular. Later he presents excise taxes as positive and points to taxes having become rate based as contributing the decline in social and political stability.

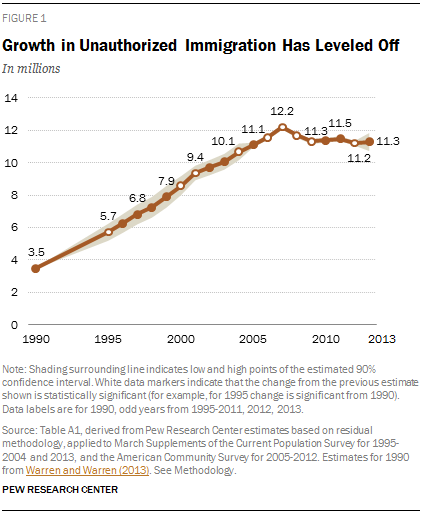

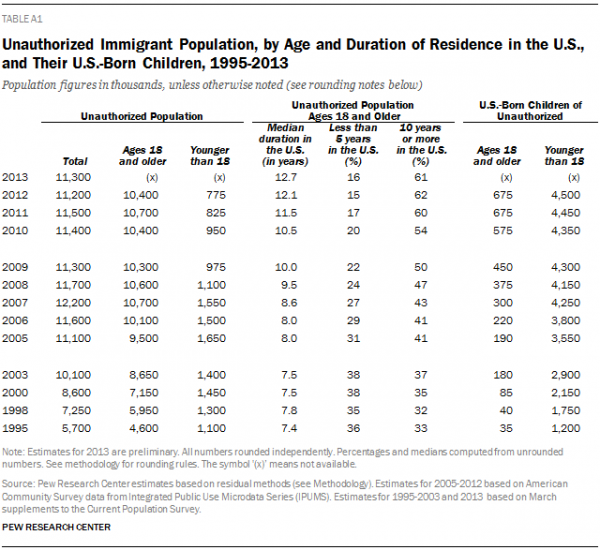

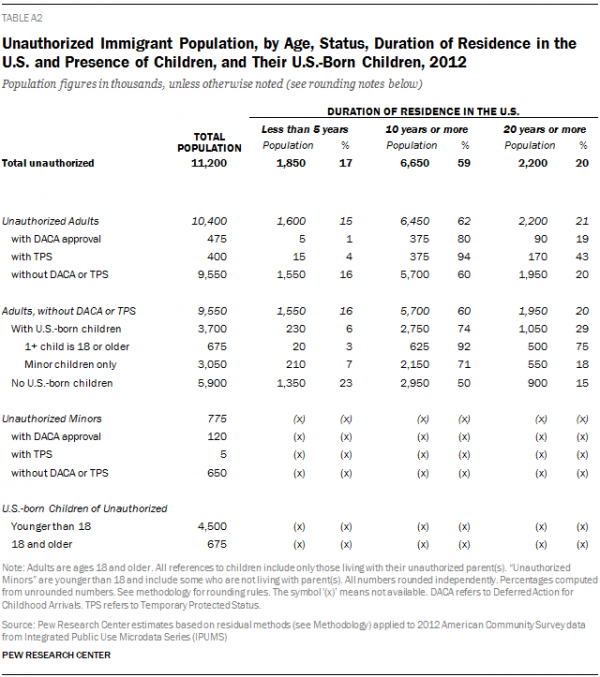

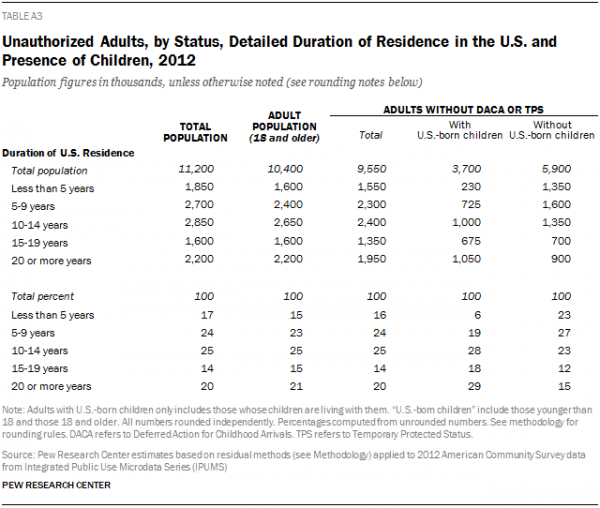

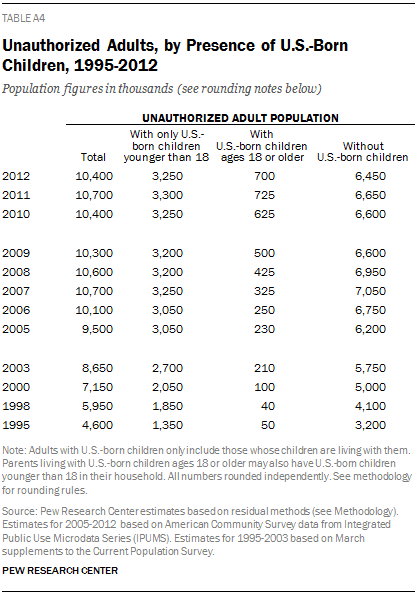

- Stefan equates Roman slaves with immigrants today. That's an off-kilter analogy, but the situational economic context of the Empire's slave population and that of the U.S.' illegal immigrant population bears no resemblance to one another. I don't disagree with the impact he attributes to the existence and consistency of the Roman slave population, but as Molyneux points out, the slaves constituted, during the period of decline, 1/3rd of population. Similarly situated immigrants in the U.S. aren't even 5% of the population, and immigrants as a whole only comprise something shy of 15%.

- Minor but since I'm listing things....Stefan glosses over the fact that when Alaric sacked Rome, Rome was a small town, even though it had the name "Rome." He doesn't explicitly mention Ravenna, which at the time of the sack was the bustling metropolis and capital of the Western Empire.

- Stefan advocates strongly for free trade and does a fine job illustrating its virtues.

- The essay has a wealth of footnotes that would enthrall any player of Trivial Pursuit. They add interest to Stefan's oration.

- At 2:08 or so, Stefan notes what strikes me and at least one other scholar, Lawrence Reed, whom Molyneux cites in another of his essays, as the keystone cause of all the other maladies that beset the Empire. I think that's a thread he should have interwoven more palpably throughout the essay, especially as he's drawing parallels to modern day America. That one feature and its erosion is the single most important factor that drives the rise and fall of great civilizations.

Notes:

- FWIW, the content, as Molyneux presents it, came to me via two courses, both of which were electives:

- HS --> AP European History -- This is the class from which I remember the history of the rise, decline and fall of the Roman Empire. Indeed one of the supplemental texts for the class had nearly that as its title. (elective insofar as one didn't have to take AP EWC, but one did have to take a European history survey class.)

- Undergrad --> American Economic History (taken as a lower level social science elective)