Delta4Embassy

Gold Member

http://medicalxpress.com/news/2015-10-antioxidant-cancer.html

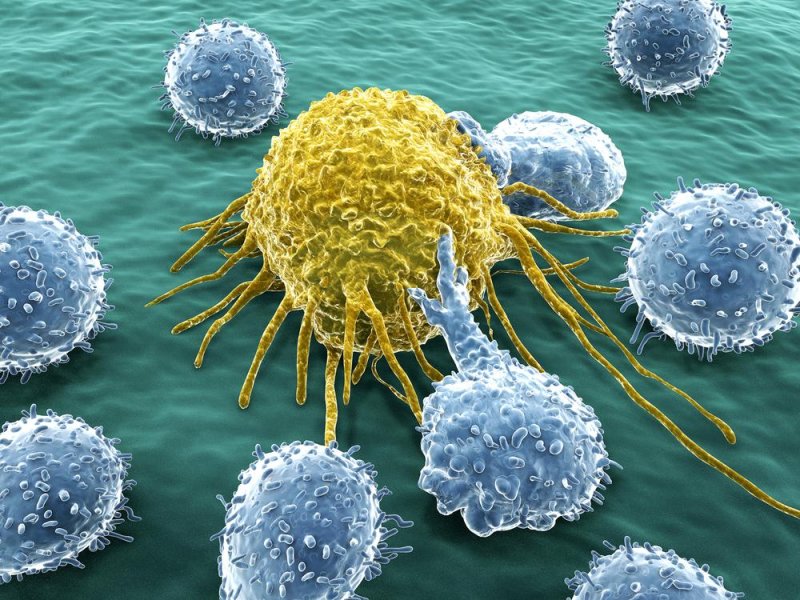

"A team of scientists at the Children's Research Institute at UT Southwestern (CRI) has made a discovery that suggests cancer cells benefit more from antioxidants than normal cells, raising concerns about the use of dietary antioxidants by patients with cancer. The studies were conducted in specialized mice that had been transplanted with melanoma cells from patients. Prior studies had shown that the metastasis of human melanoma cells in these mice is predictive of their metastasis in patients.

Metastasis, the process by which cancer cells disseminate from their primary site to other parts of the body, leads to the death of most cancer patients. The CRI team found that when antioxidants were administered to the mice, the cancer spread more quickly than in mice that did not get antioxidants. The study was published online today in Nature.

It has long been known that the spread of cancer cells from one part of the body to another is an inefficient process in which the vast majority of cancer cells that enter the blood fail to survive.

"We discovered that metastasizing melanoma cells experience very high levels of oxidative stress, which leads to the death of most metastasizing cells," said Dr. Sean Morrison, CRI Director and Mary McDermott Cook Chair in Pediatric Genetics at UT Southwestern Medical Center. "Administration of antioxidants to the mice allowed more of the metastasizing melanoma cells to survive, increasing metastatic disease burden.""

Uh-oh, take a number of antioxidants as prophylactic against cancer and other things. I hope this turns out to be another pro-pharmaceutical company mouthpieces trying to discourage preventative health measures, and not legit science.

"A team of scientists at the Children's Research Institute at UT Southwestern (CRI) has made a discovery that suggests cancer cells benefit more from antioxidants than normal cells, raising concerns about the use of dietary antioxidants by patients with cancer. The studies were conducted in specialized mice that had been transplanted with melanoma cells from patients. Prior studies had shown that the metastasis of human melanoma cells in these mice is predictive of their metastasis in patients.

Metastasis, the process by which cancer cells disseminate from their primary site to other parts of the body, leads to the death of most cancer patients. The CRI team found that when antioxidants were administered to the mice, the cancer spread more quickly than in mice that did not get antioxidants. The study was published online today in Nature.

It has long been known that the spread of cancer cells from one part of the body to another is an inefficient process in which the vast majority of cancer cells that enter the blood fail to survive.

"We discovered that metastasizing melanoma cells experience very high levels of oxidative stress, which leads to the death of most metastasizing cells," said Dr. Sean Morrison, CRI Director and Mary McDermott Cook Chair in Pediatric Genetics at UT Southwestern Medical Center. "Administration of antioxidants to the mice allowed more of the metastasizing melanoma cells to survive, increasing metastatic disease burden.""

Uh-oh, take a number of antioxidants as prophylactic against cancer and other things. I hope this turns out to be another pro-pharmaceutical company mouthpieces trying to discourage preventative health measures, and not legit science.