CSM

Senior Member

New York Times

July 27, 2006

Carl M. Brashear, 75, Diver Who Broke A Racial Barrier, Dies

By Margalit Fox

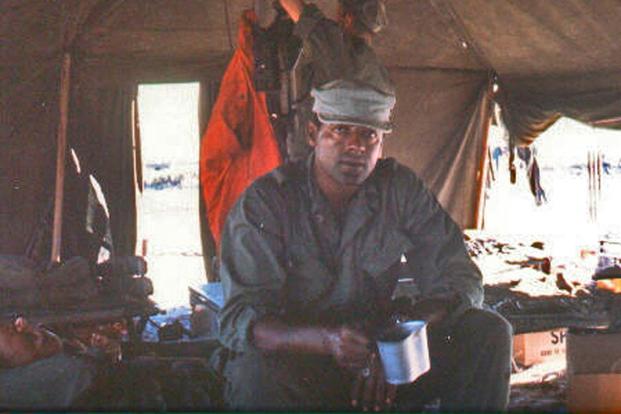

Carl M. Brashear, a son of Kentucky sharecroppers who in 1970 became the United States Navys first black master diver, and whose story was told in the 2000 movie Men of Honor, died Tuesday in Portsmouth, Va. He was 75.

The cause was heart and respiratory failure, said his former wife Junetta Brashear.

Starring Cuba Gooding Jr. as Mr. Brashear, Men of Honor chronicled its heros struggle against seemingly insurmountable odds: rural poverty, a threadbare education and the racism that pervaded the armed forces from the late 1940s, when he enlisted, until long afterward.

The movie also portrayed Mr. Brashears grueling fight to return to diving, and to attain the coveted designation of master diver, after he lost a leg as the result of a shipboard accident in 1966.

A 31-year Navy veteran, Mr. Brashear retired in 1979 as a master chief boatswains mate, the highest enlisted rank in the Navy. He was also the first person to be returned to full service as a Navy diver after losing a limb.

Mr. Brashear, who was a consultant on Men of Honor, called it a mostly faithful depiction of his life. (The brutal diving instructor played by Robert De Niro was in fact a composite of several men, he said.) But there were aspects of Mr. Brashears story that the movie did not examine, including treatment for alcoholism toward the end of his career.

Carl Maxie Brashear (pronounced bruh-SHEER) was born on Jan. 19, 1931, in Tonieville, Ky., the sixth of eight children. He left school after seventh grade to help his father work the land, but dreamed of adventure. He did not want to spend his days behind a plow.

At 17, he tried to join the Army in early 1948, but the Army did not want him. The Navy was more welcoming, and he enlisted in February 1948. (The military would be officially desegregated in June of that year.)

Like most black Navy men of the period, Mr. Brashear was placed in the stewards branch, which did chores for the officers. Assigned to the naval station at Key West, Fla., he prepared meals for white officers in the officers mess.

In 1950, Mr. Brashear was assigned to the aircraft carrier Palau. One day he watched, fascinated, as a diver slipped into the ocean to recover an airplane that had rolled overboard. Here was the adventure he had sought for so long.

He wrote to the Navy diving school, asking for admittance. He wrote again. And again. Curiously, as Mr. Brashear later recounted, his letters kept getting lost. He wrote more than 100 times before being admitted in 1954.

Few of Mr. Brashears classmates were pleased to see him. He sometimes found threatening notes with racial epithets on his bunk.

He graduated in 1955 and spent the next several years as a Navy salvage diver. But he longed to be a first-class diver, carrying out missions deep undersea. In 1960, after earning his high school equivalency diploma, he entered the Navys deep-sea diving school.

Mr. Brashear failed the course, unable to pass its rigorous science component, which included physics, medicine and mathematics. For the next three years, he studied every moment he was not on duty, and in 1963 was readmitted. He graduated in 1964 as a first-class diver, third in his class of 17.

In 1966, Mr. Brashear was aboard the Navy salvage ship Hoist off the coast of Spain, helping to recover a hydrogen bomb that had plunged into the Mediterranean after the plane carrying it crashed. As he supervised from the ship, a line broke, sending a heavy steel pipe hurtling toward the men on deck.

Mr. Brashear pushed his men out of the way, but could not avoid the pipe himself. It crushed his left leg. He lost so much blood that he was initially pronounced dead by the Spanish hospital to which he was evacuated.

After being transferred to Portsmouth Naval Hospital in Virginia, Mr. Brashear was told that his leg could be repaired enough to allow him to walk with a brace and cane. The process would take several years.

Go ahead and amputate, he told the doctors. I cant be tied up that long. Ive got to go back to diving.

He was fitted with a prosthesis, and the Navy sent him his discharge papers. He did not sign. Instead, he quietly signed his own orders for a transfer back to diving school. He dived with his new leg, had pictures taken and showed them to Navy officials. They did not believe such a feat was possible.

The Navy finally agreed to put Mr. Brashear through a series of tests, including climbing ladders with barbells strapped to his back to simulate a divers staggering load. For the final test, in a scene dramatically reproduced in the film, Mr. Brashear was required to walk 12 steps unaided, wearing nearly 300 pounds of equipment. He took the steps, and was returned to active duty as a diver.

In 1970, after more grueling tests, Mr. Brashear became a master diver, the highest designation a Navy diver can attain.

Mr. Brashears first marriage, to the former Junetta Wilcoxson, ended in divorce, as did his two later marriages, to Hattie Elam and Jeanette Brundage. He is survived by three sons from his first marriage, Dawayne, of Newark; Phillip Maxie, a helicopter pilot currently stationed in Iraq; and Patrick, of Portsmouth; three sisters, Florene Harris, Leatta English and Norma Jean Moore, all of Elizabethtown, Ky.; two brothers, Douglas, of Elizabethtown, and Edward Ray, of Indianapolis; 12 grandchildren; and 2 great-grandchildren. A fourth son from Mr. Brashears first marriage, Shazanta, died in 1996.

Despite a lifetime of hard-won achievement, Mr. Brashear spoke about Men of Honor with something approaching awe.

Not in my wildest dreams did I think this would happen, he said in an interview with CNN in 2001. Even after I lost my leg I was just doing my job.

July 27, 2006

Carl M. Brashear, 75, Diver Who Broke A Racial Barrier, Dies

By Margalit Fox

Carl M. Brashear, a son of Kentucky sharecroppers who in 1970 became the United States Navys first black master diver, and whose story was told in the 2000 movie Men of Honor, died Tuesday in Portsmouth, Va. He was 75.

The cause was heart and respiratory failure, said his former wife Junetta Brashear.

Starring Cuba Gooding Jr. as Mr. Brashear, Men of Honor chronicled its heros struggle against seemingly insurmountable odds: rural poverty, a threadbare education and the racism that pervaded the armed forces from the late 1940s, when he enlisted, until long afterward.

The movie also portrayed Mr. Brashears grueling fight to return to diving, and to attain the coveted designation of master diver, after he lost a leg as the result of a shipboard accident in 1966.

A 31-year Navy veteran, Mr. Brashear retired in 1979 as a master chief boatswains mate, the highest enlisted rank in the Navy. He was also the first person to be returned to full service as a Navy diver after losing a limb.

Mr. Brashear, who was a consultant on Men of Honor, called it a mostly faithful depiction of his life. (The brutal diving instructor played by Robert De Niro was in fact a composite of several men, he said.) But there were aspects of Mr. Brashears story that the movie did not examine, including treatment for alcoholism toward the end of his career.

Carl Maxie Brashear (pronounced bruh-SHEER) was born on Jan. 19, 1931, in Tonieville, Ky., the sixth of eight children. He left school after seventh grade to help his father work the land, but dreamed of adventure. He did not want to spend his days behind a plow.

At 17, he tried to join the Army in early 1948, but the Army did not want him. The Navy was more welcoming, and he enlisted in February 1948. (The military would be officially desegregated in June of that year.)

Like most black Navy men of the period, Mr. Brashear was placed in the stewards branch, which did chores for the officers. Assigned to the naval station at Key West, Fla., he prepared meals for white officers in the officers mess.

In 1950, Mr. Brashear was assigned to the aircraft carrier Palau. One day he watched, fascinated, as a diver slipped into the ocean to recover an airplane that had rolled overboard. Here was the adventure he had sought for so long.

He wrote to the Navy diving school, asking for admittance. He wrote again. And again. Curiously, as Mr. Brashear later recounted, his letters kept getting lost. He wrote more than 100 times before being admitted in 1954.

Few of Mr. Brashears classmates were pleased to see him. He sometimes found threatening notes with racial epithets on his bunk.

He graduated in 1955 and spent the next several years as a Navy salvage diver. But he longed to be a first-class diver, carrying out missions deep undersea. In 1960, after earning his high school equivalency diploma, he entered the Navys deep-sea diving school.

Mr. Brashear failed the course, unable to pass its rigorous science component, which included physics, medicine and mathematics. For the next three years, he studied every moment he was not on duty, and in 1963 was readmitted. He graduated in 1964 as a first-class diver, third in his class of 17.

In 1966, Mr. Brashear was aboard the Navy salvage ship Hoist off the coast of Spain, helping to recover a hydrogen bomb that had plunged into the Mediterranean after the plane carrying it crashed. As he supervised from the ship, a line broke, sending a heavy steel pipe hurtling toward the men on deck.

Mr. Brashear pushed his men out of the way, but could not avoid the pipe himself. It crushed his left leg. He lost so much blood that he was initially pronounced dead by the Spanish hospital to which he was evacuated.

After being transferred to Portsmouth Naval Hospital in Virginia, Mr. Brashear was told that his leg could be repaired enough to allow him to walk with a brace and cane. The process would take several years.

Go ahead and amputate, he told the doctors. I cant be tied up that long. Ive got to go back to diving.

He was fitted with a prosthesis, and the Navy sent him his discharge papers. He did not sign. Instead, he quietly signed his own orders for a transfer back to diving school. He dived with his new leg, had pictures taken and showed them to Navy officials. They did not believe such a feat was possible.

The Navy finally agreed to put Mr. Brashear through a series of tests, including climbing ladders with barbells strapped to his back to simulate a divers staggering load. For the final test, in a scene dramatically reproduced in the film, Mr. Brashear was required to walk 12 steps unaided, wearing nearly 300 pounds of equipment. He took the steps, and was returned to active duty as a diver.

In 1970, after more grueling tests, Mr. Brashear became a master diver, the highest designation a Navy diver can attain.

Mr. Brashears first marriage, to the former Junetta Wilcoxson, ended in divorce, as did his two later marriages, to Hattie Elam and Jeanette Brundage. He is survived by three sons from his first marriage, Dawayne, of Newark; Phillip Maxie, a helicopter pilot currently stationed in Iraq; and Patrick, of Portsmouth; three sisters, Florene Harris, Leatta English and Norma Jean Moore, all of Elizabethtown, Ky.; two brothers, Douglas, of Elizabethtown, and Edward Ray, of Indianapolis; 12 grandchildren; and 2 great-grandchildren. A fourth son from Mr. Brashears first marriage, Shazanta, died in 1996.

Despite a lifetime of hard-won achievement, Mr. Brashear spoke about Men of Honor with something approaching awe.

Not in my wildest dreams did I think this would happen, he said in an interview with CNN in 2001. Even after I lost my leg I was just doing my job.