- Aug 16, 2011

- 127,789

- 24,068

- 2,180

Some facts about the English language that a lot of folks may not know (but should).

25 maps that explain the English language - Vox

25 maps that explain the English language - Vox

Follow along with the video below to see how to install our site as a web app on your home screen.

Note: This feature currently requires accessing the site using the built-in Safari browser.

.

Claude S. Fischer, Mike Hout, Aliya Saperstein

Immigrants to the US are learning English more quickly than previous generations

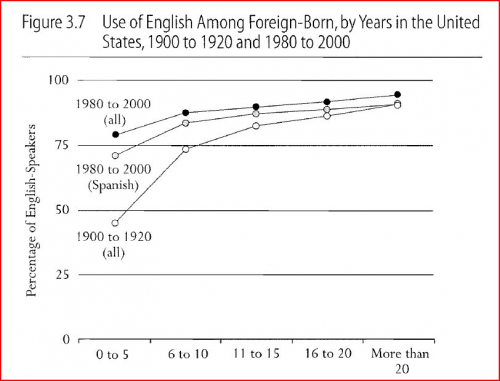

Concerns about whether immigrants are assimiliating in the US often focus on criticisms that they're not learning English quickly enough (think of outrage over phone systems that ask you to select English or Spanish). But in fact immigrants to the US today are learning and using English much more quickly than immigrants at the turn of the 20th century. More than 75 percent of all immigrants, and just less than 75 percent of Spanish-speaking immigrants, speak English within the first five years, compared to less than 50 percent of immigrants between 1900 and 1920.

Que?

Claude S. Fischer, Mike Hout, Aliya Saperstein

Immigrants to the US are learning English more quickly than previous generations

Concerns about whether immigrants are assimiliating in the US often focus on criticisms that they're not learning English quickly enough (think of outrage over phone systems that ask you to select English or Spanish). But in fact immigrants to the US today are learning and using English much more quickly than immigrants at the turn of the 20th century. More than 75 percent of all immigrants, and just less than 75 percent of Spanish-speaking immigrants, speak English within the first five years, compared to less than 50 percent of immigrants between 1900 and 1920.

.

Olaf Simons

The Great Vowel Shift

If you think English spelling is confusing — why "head" sounds nothing like "heat," or why "steak" doesn't rhyme with "streak," and "some" doesn't rhyme with "home" — you can blame the Great Vowel Shift. Between roughly 1400 and 1700, the pronunciation of long vowels changed. "Mice" stopped being pronounced "meese." "House" stopped being prounounced like "hoose." Some words, particularly words with "ea," kept their old pronounciation. (And Northern English dialects were less affected, one reason they still have a distinctive accent.) This shift is how Middle English became modern English. No one is sure why this dramatic shift occurred. But it's a lot less dramatic when you consider it took 300 years. Shakespeare was as distant from Chaucer as we are from Thomas Jefferson.