Somewhat Damaged

Rookie

- Aug 15, 2015

- 1

- 1

- 1

Dirty Hands

The success of U.S. policy in El Salvador -- preventing a guerrilla victory -- was based on 40,000 political murders

By Benjamin Schwarz, RAND Corp., Dec. 1998

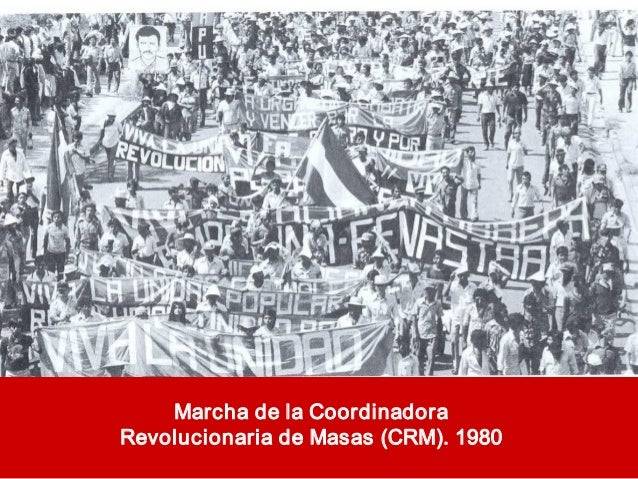

In the mid-1970s, there was a growth of "popular organizations", made up of opposition labor unions, student and peasant groups, supported by the Church, and controlled by the FMLN-FDR. They frequently engaged in mass public demonstrations - demanding better wages and working conditions, social reform, and the release of political prisoners. They occupied and sometimes took over offices, factories, embassies, churches and radio stations to call national and world attention to their grievances. In one secret cable, the State Department had assumed the inevitability of such activities culminating in "terrorism and sabotage, demonstrations, strikes and mob violence which if protracted might turn into successful general strike and, internal revolution." Thus in 1977:

Weakness and Deceit: U.S. Policy and El Salvador, Ray Bonner, 1984

the Salvadoran government enacted the Law for the Defense and Guarantee of the Public Order — known as the Ley de Orden — it was a Draconian measure, "practically a license to kill," said Professor Baloyra. The American Association for the International Commission of Jurists roundly condemned it, noting among other things that it made an "invidious distinction between crimes against, for example, businessmen and those against peasants."

The law restricted all rights to organize, to strike, and even to express any opinions "through word of mouth, through writing or through any other means, that tend to destroy the social order." Three of the country's leading bishops, including the archbishop, attacked the law because it "leaves unprotected the greatest number of Salvadorans, the poor, the workers, and farmhands, for they are impeded from having recourse to the pressure of public opinion in their search for justice, while the rich and powerful are in fact well organized. The bishops went on to declare, as they had many times, that "permanent, institutionalized injustice that keeps the majority of our people in inhuman conditions is truly the root of violence."

[U.S.] Ambassador Devine defended the public order law. "We believe any government has the full right and obligation to use all legal means at its disposal to combat terrorism," he told the American Chamber of Commerce in a speech the day after the law was enacted. Carter's appointment of Devine as his ambassador to El Salvador was one of the clearest signals to the Salvadoran military that it could ignore the administration's human rights pronouncements.

State repression intensified but opposition activity only grew more militant. A State of Siege was then imposed in March 1980, which effectively limited or ended most civil liberties including "freedom of movement . . . and freedom of assembly . . . [and permitted] detention for six months without charge or access to counsel, . . . extrajudicial confessions—for example those coerced coerced through torture—to be used as evidence." Amnesty International later recognized this as legislation "facilitat[ing] 'death squad' 'disappearances' and killings", in that it allowed the military to capture individuals without acknowledging that they had done so. In this situation, people could be abducted, tortured, and murdered by intelligence agents and they could blame the "unacknowledged arrest" on vigilante "extremists".

"The 'dirty war' theory certainly had some adherents here in 1979 to 1981," said a U.S. diplomat in San Salvador. "There were people willing to kill a lot of people to eliminate the supporters of the FMLN. The horror years of '80 and '81 had a lot to do with breaking the FMLN in this city. [Death squad killing] wasn't indiscriminate."

The immediate goal of the Salvadoran army and security forces—and of the United States in 1980, was to prevent a takeover by the leftist-led guerrillas and their allied political organizations. At this point in the Salvadoran conflict the latter were much more important than the former. The military resources of the rebels were extremely limited and their greatest strength, by far, lay not in force of arms but in their "mass organizations" made up of labor unions, student and peasant organizations that could be mobilized by the thousands in El Salvador's major cities and could shut down the country through strikes. (Washington Post correspondent Christopher Dickey, 1984)

U.S. military and CIA manuals prepped the intelligence services, accordingly:

Another function of the CI [counterintelligence] agents is to recommend CI targets for neutralization. Organizations or groups that are able to be a potential threat to the government must be identified as targets. Even though the threat may not be apparent, insurgents frequently hide subversive activity behind front organizations. Examples of hostile organizations or groups are paramilitary groups, labor unions, and dissident groups. ("Terrorism and the Urban Guerilla," U.S. Army, p. 69)

The CI agent must consider all the organizations as possible guerrilla sympathizers. He must train and place his employees inside these organizations so that they may inform him about their activities and discover any indication of a latent insurrection. ("Handling of Sources", CIA, Chapter V, p. 61)

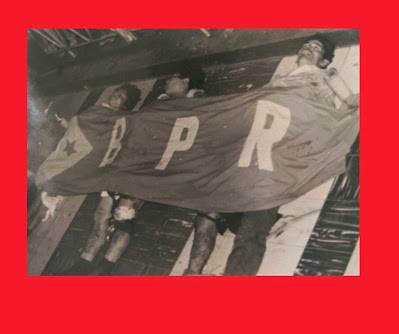

Neutralized bodies of anti-government popular organization, the BPR [Popular Revolutionary Bloc]. San Salvador. 1981.

As a RAND Corporation specialist, Benjamin Schwarz spent two years assessing U.S. policy in El Salvador for the Defense Department:

when in late 1980 a rebel victory appeared imminent unless the United States provided military and other forms of aid to the Salvadoran regime, Carter chose to assist the Salvadoran government, and thus hesitantly embarked on the policy that the Reagan Administration would later pursue with alacrity. Although the Reagan Administration's fundamental policy toward El Salvador didn't differ substantively from its predecessor's, the new Administration did immediately escalate the rhetoric.

By the time Reagan entered the Oval Office, on January 20, 1981, the guerrillas' "final offensive," launched at the beginning of the month, had failed, even though the Salvadoran regime and military were at their weakest and most divided. The rebels would never again come so close to seizing power. Although the FMLN had made important military gains in the countryside during the offensive, the success of its strategy rested on the ability of its affiliated "popular organizations" -- coalitions of workers', peasants', and students' unions -- to mobilize a simultaneous general strike in San Salvador, thereby crippling the country and forcing the military to spread itself too thin. But whereas the popular organizations had assembled hundreds of thousands of marchers in the capital just a year earlier, the general strike called to coincide with the final offensive failed to materialize, and thus the offensive petered out.

With lavish brutality the military failed to distinguish between dissenters and revolutionaries; many of its victims were unconnected to the FMLN, but enough were connected that the guerrillas' political infrastructure was destroyed. The guerrillas simply did not have enough allies left alive in San Salvador to organize a general strike.

Of the many thousands of bodies found, a very high proportion showed signs of torture "including dismemberment, beating, acid burns, flaying, scalping, castration, strangulation, sexual violation, and evisceration." The Executive Director of Americas Watch writes:

death squads were never apprehended or prosecuted; they operated with impunity during curfew hours; they passed police checkpoints without challenge; the security forces sometimes blocked streets to permit death squads to operate without interruption; uniformed forces sometimes conducted joint operations with nonuniformed death squads; bodies were dumped in heavily patrolled areas; death squads had access to good intelligence; the volume of death squad killing was adjusted in response to pressure on governmental forces; and so on.

Meanwhile, the CIA's hidden hand was operating behind the scenes:

The American Connection: State Terror and Popular Resistance in Guatemala, Michael McClintock, 1985

Citing US Embassy and Salvadorean military sources, [an article in Reuters] states that the Central Intelligence Agency had "penetrated" police and military intelligence years before and had full information on the officers and agencies running the "death squad" programmes. According to an Embassy spokesman, however, the US's hands were tied in so far as stopping the killings; El Salvador might not survive the disruption of these traditional practices: "If you pursue the squads it is going to cut so far back into the fabric of Salvadorean society you may face the destabilisation of the society", one US Embassy official said.

Monthly totals of counter-terror killings remained high throughout 1981, although the figures indicated lulls in the killings at regular six-monthly intervals. These six month periods coincided with a US government human rights reporting calender; the US congress required the President to provide a bi-annual "certification" that progress was being made in human rights observance as a condition for further aid. In 1982, ... A pattern similar to 1981's, in relation to the US human rights certification timetable, can again be discerned, suggesting a capacity to rein in the counter-terror programme when political expediency so demanded.

Weakness and Deceit: U.S. Policy and El Salvador, Ray Bonner, Times Books, 1984, p. 264

In El Salvador the Reagan administration unleashed a massive intelligence-gathering operation, spending at least $50 million during just the first two years. More than 150 CIA operatives roamed through the tiny country, infiltrating peasant organizations...

Central America Inside Out: The Essential Guide to Its Societies, Politics, and Economies, Tom Barry, 1991

In addition, the CIA and the U.S. embassy have regularly shared intelligence information on leftists and popular leaders with military and police intelligence units.

Behind the Death Squads: An exclusive report on the U.S. role in El Salvador's official terror, Allan Nairn, the Progressive, May 1984

Colonel Carranza confirmed this relationship. U.S. intelligence officials "have collaborated with us in a certain technical manner, providing us with advice," says Carranza. "They receive information from everywhere in the world, and they have sophisticated equipment that enables them to have better information or at least confirm the information we have. It's very helpful."

Neutralized bodies of anti-government popular organization, LP-28 [Popular Leagues of February 28th]. San Salvador. 1981.

After 1981, the rate of political murders gradually declined as the army ran out of people to kill. They were either already killed or they went into hiding. The Reagan administration said this was progress in human rights. Americas Watch posed the question to Congress. "Is successful state terrorism progress?":

Our Own Backyard: The United States in Central America, 1977-1992, William M. LeoGrande, Nov 18, 2009

The popular organizations, which had been the core of the left's political strength in 1979, had been exterminated by 1983. Their demise had considerable military importance.

In 1982 and 1983 the Salvadoran regime remained on the defensive, but the guerrillas continued to prove incapable of following up their increasing success on the battlefield with the necessary final blow -- an insurrection in the capital. As I was told repeatedly by U.S. military and intelligence personnel who were as clear-eyed as they were aghast, the dirty little secret shared by those determined to prevent an FMLN takeover -- a group that included both the Salvadoran armed forces and the United States government -- was this: the death squads worked.

As the American commitment to El Salvador deepened, the United States grew increasingly determined, for a mixture of altruistic and practical reasons, to put a stop to the carnage. Nevertheless, since the purpose of that commitment was to prevent an FMLN victory, there is no escaping the fact that the success of the U.S. policy was built on a foundation of corpses. A former U.S. military attaché to El Salvador recalled to me that in the middle of one of his many demarches to the Salvadoran high command on the need to stop death-squad killings, a high-ranking officer retorted in a dismissive tone that talk about respect for human rights was a luxury the United States could afford only because of the cold efficiency of the death squads in the early 1980s: "We cleaned up San Salvador for you." The attaché found the argument appalling -- and correct.

Hence:

NACLA Report on the Americas, Volume 18, North American Congress on Latin America, 1984

In November 1983, the Administration responded to congressional attempts to condition military aid on human rights improvements with a campaign against individual officers implicated in death squad activity. This high-visibility drive left death squad structures intact but sowed bitterness among officers. "We had a meeting in Washington," remembered Guillermo Sol, patriarch of one of the 14 families and a founding member of ARENA. "The White House people said we had to be patient with these congressmen. They said we needed their support for now and that, anyway, who would you rather have on your side, a bunch of congressmen or Jeane Kirkpatrick?" For the Salvadorean Right, all this was galling: "We learned our way of operating from you," complained one senior officer, "I studied in the Canal Zone, I studied in North Carolina. You taught me how to kill communists and you taught me very well. And now you come along and persecute my companeros for doing their jobs, for doing what you trained them to do."

Death from a Distance: Washington's Role in El Salvador's Death Squads, Jefferson Morley, Washington Post, March 28, 1993

In December 1983 Vice President Bush was dispatched to San Salvador, where he delivered a speech criticizing death squads of the right and left. He handed over to Salvadoran commanders a list of officers known to have overseen many lavishly sadistic murders. Among them were the heads of the S-2 intelligence offices of the Treasury Police and the National Police.

The Bush visit had the desired effect. "The activities of the death squads decreased noticeably in the first months" of 1984, the Truth Commission observed. One could say that U.S. officials had acted idealistically to reduce human suffering in a difficult political situation. One could also note that the command structure of the Salvadoran death squads was responsive to the directives of senior U.S. policymakers.

After December 1983, the number of murders attributed to military death squads slowly but steadily declined until 1988, when the murders again increased. The military's massacres in the countryside also declined. But the bureaucracy of death remained in place, subject to the military chain of command, whose leaders were in daily contact with U.S. advisers.

The moral question facing Congress (and the media) concerns notions of personal responsibility of U.S. policymakers. U.S. officials and officers were "the planners, the organizers" of the expanded Salvadoran military-intelligence agencies in the 1980s. Young Salvadoran men, conscripted to carry out their designs, were usually the ones who wielded the "fatal instrument" -- i.e., a U.S.-supplied gun. What are their degrees of responsibility?

Salvador in Iraq: Flash Back, Jonathan D. Tepperman, Council on Foreign Relations, April 5, 2005

Thomas Pickering, who was ambassador to El Salvador from 1983 to 1985, says that, while it was U.S. policy to publicly denounce the death squads, their "kind of tactics [were] tacitly supported by the U.S. government, even though [they] were freelance." Other analysts are more blunt. "We did back the guys who went after the bad guys," says Lawrence Korb, assistant secretary of defense from 1981 to 1985. "And [we] defined 'bad guys' pretty broadly."

With the "dirty work" completed by late 1983, death squad killings dropped sharply to an average of 29 a month under U.S. management, which had been getting more and more indiscriminate at the time.

But:

Central America Inside Out: The Essential Guide to Its Societies, Politics, and Economies, Tom Barry, 1991

With the reconstitution of the popular movement in the late 1980s, death-squad violence again became common.

To be continued.