Widdekind

Member

- Mar 26, 2012

- 813

- 35

- 16

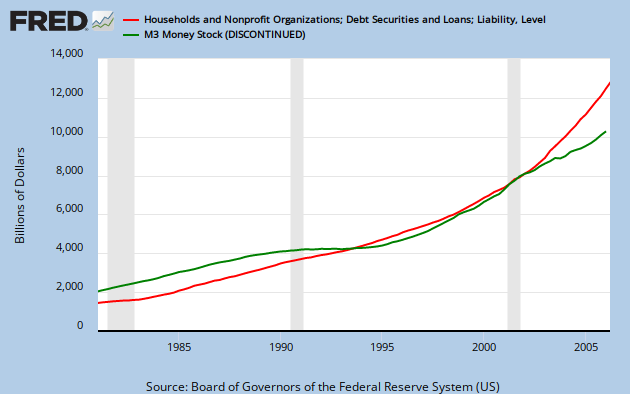

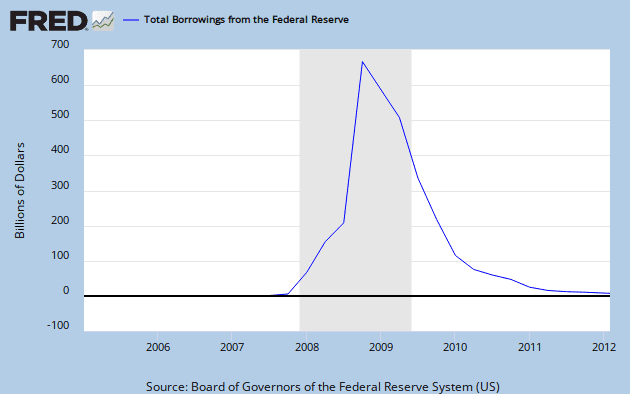

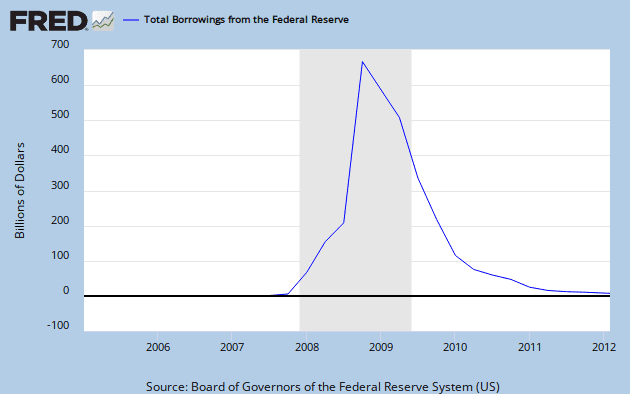

In 2008, banks "borrowed" $0.7T from the Federal Reserve (FR)

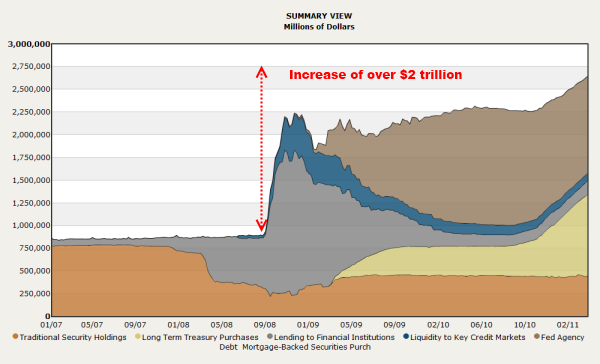

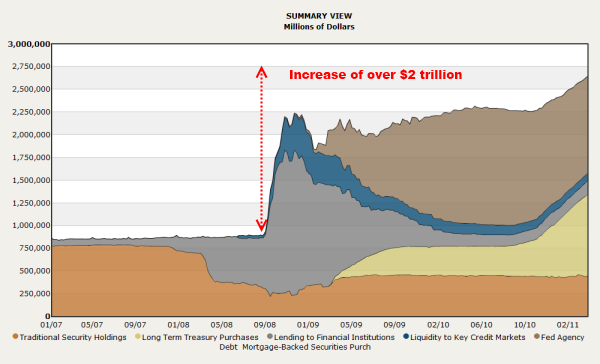

To fund the "loans", the FR initially liquidated $0.5T of "traditional securities" from its "balance sheet" portfolio, on the open market. With the Money, the FR purchased toxic assets from banks, adding the assets, to the FR "balance sheet". But as the bailout continued, additional "loans" were still required. So, the FR subsequently printed $2T of new Money, with which the FR purchased over $1T of additional toxic assets from banks, again adding the assets, to the FR portfolio.

To fund the "loans", the FR initially liquidated $0.5T of "traditional securities" from its "balance sheet" portfolio, on the open market. With the Money, the FR purchased toxic assets from banks, adding the assets, to the FR "balance sheet". But as the bailout continued, additional "loans" were still required. So, the FR subsequently printed $2T of new Money, with which the FR purchased over $1T of additional toxic assets from banks, again adding the assets, to the FR portfolio.

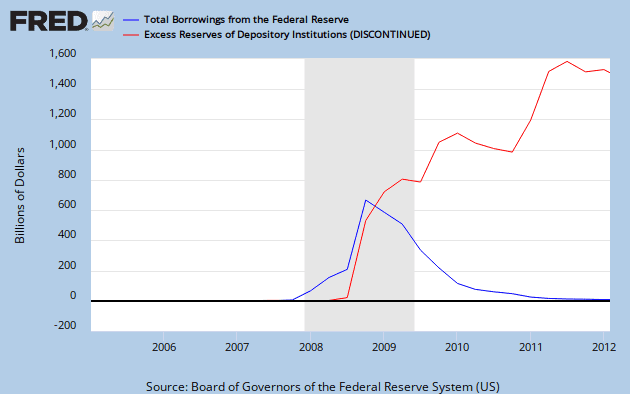

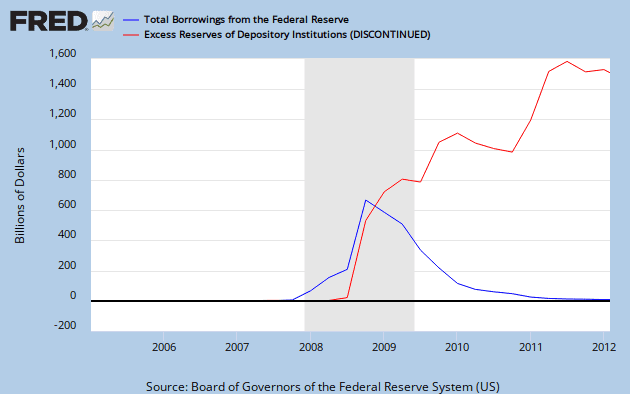

In 2009, the FR began liquidating toxic assets from its "balance sheet", selling them back to banks. With the Money, the FR purchased US Government debt assets, from those same banks. By 2010, most toxic assets had been, thusly, exchanged for US Government bonds. Banks were "bailed out", and now retain their toxic assets, plus the $2T they received from the FR, for the sale of US Government bonds. Banks are keeping the $2T in the FR, as "excess Reserves", on which they are now earning 0.25% interest:

In 2009, the FR began liquidating toxic assets from its "balance sheet", selling them back to banks. With the Money, the FR purchased US Government debt assets, from those same banks. By 2010, most toxic assets had been, thusly, exchanged for US Government bonds. Banks were "bailed out", and now retain their toxic assets, plus the $2T they received from the FR, for the sale of US Government bonds. Banks are keeping the $2T in the FR, as "excess Reserves", on which they are now earning 0.25% interest:

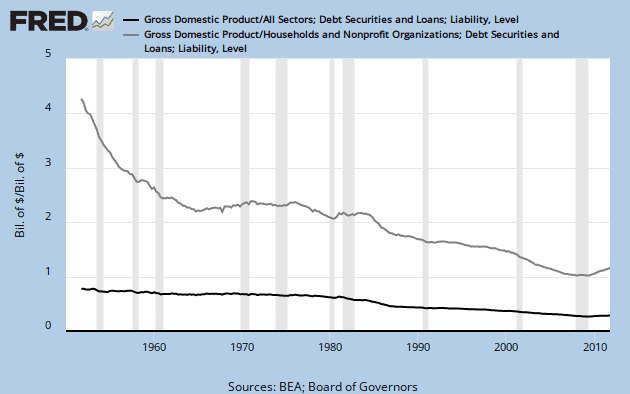

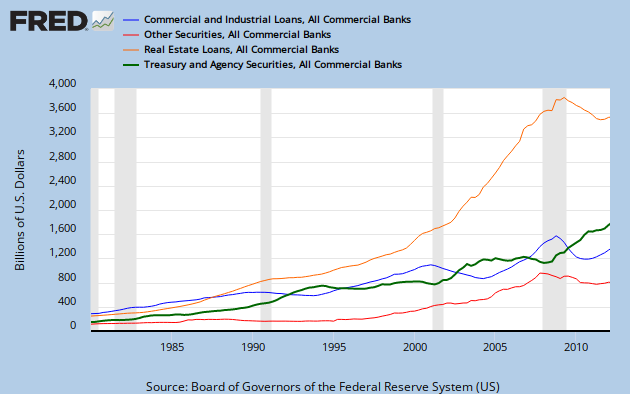

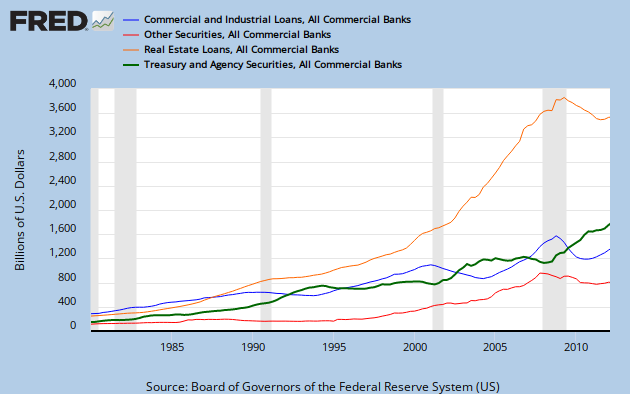

Banks have dis-invested from $1T of real-estate (property), business & industry (plant & equipment), and other securities; and re-invested into $0.5T of Government bonds, seemingly "shying away" from the private sector:

Banks have dis-invested from $1T of real-estate (property), business & industry (plant & equipment), and other securities; and re-invested into $0.5T of Government bonds, seemingly "shying away" from the private sector:

Last edited: