usmbguest5318

Gold Member

Thread Rules/Structure:

Along with the standing SDF rules requiring posts be on-topic, thus pertaining only to the central ideas in the "Thread Discussion Rubric" section of this opening post, and that "members [posts] may not deviate from the structure and shall respect all guidelines set forth in the opening post," this thread's discussion structure guidelines are as follows:

Background and Credit Attribution:

(Note: The background and credit are not fodder for the thread's discussion.)

One means Congressional Republicans implemented to pay for the APRP's tax cuts is by adopting the chained Consumer Price Index (CPI) to annually adjust tax brackets and other tax parameters. The chained CPI grows more slowly than the current inflation measure, so taxpayers across the board would pay slightly more because the sums of money they earn increase with inflation, thereby gradually pushing people into higher tax brackets. Consequently, the impact of the switch, though small is nonetheless a tax increase for everyone and the the increase compounds.

The APRP's tax cuts for high-income households reflect a series of provisions that provide large benefits to the wealthy but little or nothing to everyone else. These include:

What is Indexing Taxes?

That all sounds basically fair, and to be sure, the intent of indexing is to inject a degree and genre of equitability into the tax code. The problems with the APRP using the CCPIU, however, are multiple:

The focus here is on the APRP's percentage changes in households’ after-tax income, the measure that most likely best quantifies how tax law provisions affect households across the income spectrum. That’s because what affects people’s standard of living is a change in their after-tax (“disposable”) income, and looking at changes in after-tax incomes in percentage terms allows for fair comparisons among groups with widely different average incomes. This measure (excluding the impact of estate tax changes) can be calculated directly from the estimates that JCT presents.

For example, the JCT estimates households having incomes over $1M in 2027 will face a tax rate of 31.7 percent under the final bill, versus 32.1 percent under current law. Millionaires thus would have 68.3% of their income left after taxes under the APRP, versus 67.9% under pre-APRP law. The percentage change in after-tax income due to the APRP is thus calculated by comparing these two estimates. For millionaires, this calculation shows that, using the JCT's estimates, the final bill would increase after-tax incomes by 0.6 percent on average in calendar year 2027 (68.3 percent / 67.9 percent – 1 = 0.6 percent).

Other Organizations' Analysis of the CCPIU's Impact: [1]

The new tables from JCT, Congress’ official estimator of tax legislation, show how the bill affects households, on average, in different parts of the income distribution for 2019 and every second year thereafter until 2027. Because the JCT estimates exclude the bill’s estate tax cut and present a limited set of distributional measures, understanding them requires some analysis and adjustment. Below is discussed what the JCT tables show about the impact of the bill, both in 2025 and in 2027.

The focus here is on the APRP's percentage changes in households’ after-tax income, the measure that most likely best quantifies how tax law provisions affect households across the income spectrum. That’s because what affects people’s standard of living is a change in their after-tax (“disposable”) income, and looking at changes in after-tax incomes in percentage terms allows for fair comparisons among groups with widely different average incomes. This measure (excluding the impact of estate tax changes) can be calculated directly from the estimates that JCT presents.

For example, the JCT estimates households having incomes over $1M in 2027 will face a tax rate of 31.7 percent under the final bill, versus 32.1 percent under current law. Millionaires thus would have 68.3% of their income left after taxes under the APRP, versus 67.9% under pre-APRP law. The percentage change in after-tax income due to the APRP is thus calculated by comparing these two estimates. For millionaires, this calculation shows that, using the JCT's estimates, the final bill would increase after-tax incomes by 0.6 percent on average in calendar year 2027 (68.3 percent / 67.9 percent – 1 = 0.6 percent).

Closing Rubric Remarks:

The code doesn’t only index tax brackets. Some other provisions, including the standard deduction, the personal exemption, Earned Income Tax Credit, and the Alternative Minimum Tax, are also indexed for inflation.

Many economists believe that chained CPI more accurately reflects inflation by accounting for the way consumers respond to price changes. The classic example: If the price of oranges rises, consumers may buy more apples. CCPIU does a better job reflecting that change, though it has some disadvantages as well. If you want to know more, here is a nice explanation by my Tax Policy Center colleague Rob McClelland, written when he was at the Congressional Budget Office.

But the bottom line is that chained CPI is consistently lower than traditional CPI-U. Using CCPIU may result in a more accurate inflation adjustment, but it also raises taxes for many since those indexed provisions of the Tax Code would be less generous over time than under today’s methodology.

That means people would pay higher income taxes than under current law. It would especially hit low- and moderate-income households that rely on the CTC and standard deduction, but it would affect all taxpayers in some way, though taking longer, far longer, to percolate into the upper income brackets. And unlike proposals to repeal, say, itemized deductions, people for years to come not only will not notice, and likely not understand it if they do notice it, this hidden tax increase.

Notes:

Along with the standing SDF rules requiring posts be on-topic, thus pertaining only to the central ideas in the "Thread Discussion Rubric" section of this opening post, and that "members [posts] may not deviate from the structure and shall respect all guidelines set forth in the opening post," this thread's discussion structure guidelines are as follows:

- If you cannot or don't want to support your claims, ideas, conclusions and/or premises with rigorously performed empirical analysis -- yours or someone else's -- don't post in this thread unless the quantity of posts prior to your first post exceeds 200 posts.

This thread is about what you and others have credibly shown, empirically. It is not at all about what you hope or believe is/will be so and that you just want to share. - Refutations of and attacks on others' economic/financial analysis, assertions and conclusions must specifically show empirically the flaw(s) in methodology the other person used to arrive at their conclusions. Merely and without accompanying empirical analysis deriding or denying someone else's conclusions is not, for this thread, an acceptable remark to post.

- All economic/financial impact claims must be supported with links to rigorously developed content supporting them. Alternatively, you can provide your own, original empirical analysis and related conclusions; however, if you do so, you must also provide a full explication of the methodology you used to arrive at them.

Background and Credit Attribution:

(Note: The background and credit are not fodder for the thread's discussion.)

Credit Attribution:

Background:

What is "chained CPI," "superlative CPI," or "chained CPI-U" (they are different terms for the same thing. "CCPIU" is the acronym I'll use)?

Other:

The bill called the Jobs and Tax Cut Act (JTCA), which was a bill not a law, was enacted into law with the name "An Act to provide for reconciliation pursuant to titles II and V of the concurrent resolution on the budget for fiscal year 2018." Henceforth in this thread, the enacted law is referred to as "APRP."

- This thread was inspired by Natural Citizen's post in another thread.

- The discussion rubric is my aggregation of content from several sites/reports along with my own remarks.

What is "chained CPI," "superlative CPI," or "chained CPI-U" (they are different terms for the same thing. "CCPIU" is the acronym I'll use)?

An excellent high-level discussion of the CCPIU is below.

Written high-level discussions of it is found here:

Written high-level discussions of it is found here:

- What You Need to Know About ‘Chained CPI’

- Differences Between the Traditional CPI and the Chained CPI

- Inflation Indexation in Major Federal Benefit Programs: Impact of the Chained CPI -- The focus of this discussion is on the impact to seniors/retirees of using CCPIU for Social Security indexing. I included this link because you can be sure that in 2018, the GOP will attempt to "meddle" with Social Security, and altering the indexing approach will almost certainly be among the changes.

- Budgetary and Distributional Effects of Adopting the Chained CPI

- Consumer Prices, the Consumer Price Index, and the Cost of Living

- The Consumer Price Index (Updated 06/2015)

- Additional Bureau of Labor Statistics' documents found here: Methodology Resources Consumer Price Index

- The Chained Consumer Price Index: What Is It and Would It Be Appropriate for Cost-of-Living Adjustments?

- The Chained CPI: A Painful Cut in Social Security Benefits and a Stealth Tax Hike

- A Reconciliation between the Consumer Price Index and the Personal Consumption Expenditures Price Index

- Price measurement in the United States: a decade after the Boskin Report

- Though in the first year of implementation the CCPIU's impact is small, the effects are cumulative, similar to compounding interest.

- There is no clearly partisan preference for or against indexing with the CCPIU. Politicians and economists in both major parties favor and oppose it.

Other:

The bill called the Jobs and Tax Cut Act (JTCA), which was a bill not a law, was enacted into law with the name "An Act to provide for reconciliation pursuant to titles II and V of the concurrent resolution on the budget for fiscal year 2018." Henceforth in this thread, the enacted law is referred to as "APRP."

Thread Discussion Rubric for the Thread Topic which is "The "Hidden" Tax Increase Because of the APRP Adopting the CCPIU"

One means Congressional Republicans implemented to pay for the APRP's tax cuts is by adopting the chained Consumer Price Index (CPI) to annually adjust tax brackets and other tax parameters. The chained CPI grows more slowly than the current inflation measure, so taxpayers across the board would pay slightly more because the sums of money they earn increase with inflation, thereby gradually pushing people into higher tax brackets. Consequently, the impact of the switch, though small is nonetheless a tax increase for everyone and the the increase compounds.

The APRP's tax cuts for high-income households reflect a series of provisions that provide large benefits to the wealthy but little or nothing to everyone else. These include:

- corporate rate cuts, the benefits of which flow overwhelmingly to wealthy investors and CEOs;

- the estate tax cut;

- a tax cut for “pass-through” income, or income that owners of businesses such as partnerships, S corporations, and sole proprietorships claim on their individual tax returns and that is taxed at the same rates as wages and salaries under current law;

- the reduction in the Alternative Minimum Tax, which is designed to ensure that the wealthiest households pay at least some minimum level of tax; and

- a cut in the top individual income tax rate.

What is Indexing Taxes?

Many features of tax systems are defined by fixed dollar amounts. For instance, personal income taxes usually have various tax rates starting at different income levels. If these fixed income levels aren’t adjusted periodically, one's taxes can go up substantially simply because of inflation. This hidden tax hike is popularly known as “bracket creep.”

Take, for example, a hypothetical state that taxes the first $20,000 of income at 2% and all income above $20,000 at 4%. A person, call her Henrietta, who makes $19,500 will only pay tax at the 2% tax rate. But over time, if this person’s salary grows at the rate of inflation, she will find herself paying at a higher rate -- even though she’s not any richer in real terms. In this example, suppose the rate of inflation is five percent a year and the person gets salary raises that are exactly enough to keep up with inflation. After four years, that means a raise to $23,702 (that’s a 5%/year raise from $19,500). Now part of Henrietta’s income will be in the higher 4% bracket -- even though, in terms of the cost of living and ability to pay, because the prices she must pay for goods and services, her income hasn’t gone up at all.

Of course, the problem of “bracket creep” is not limited to tax brackets. Any feature of an income tax that is based on a fixed dollar amount will have inflationary effects. In many states, this means that tax breaks designed to provide low-income tax relief -- including exemptions, standard deductions, and most tax credits -- are worth a little bit less to taxpayers every year. When all these small impacts are added up, the long-term effect can be a substantial tax hike -- and one that falls hardest on low- and middle-income taxpayers.

For example, when the Illinois income tax was adopted in 1969, the state’s personal exemption was set at $1,000 -- and was subsequently left unchanged for thirty years. 1998 legislation doubled the exemption to $2,000 -- but if the exemption had kept up with inflation since 1969, it would have been worth $5,800 in 2010. In other words, the Illinois personal exemption is worth $3,800 less than it originally was. As a result, Illinois taxpayers paid about $1.5B more in income taxes in 2010 than they would have if the exemptions had been adjusted to preserve their 1969 value. Of course, Illinois lawmakers never voted to enact such a regressive tax hike -- but this tax hike is the direct consequence of not indexing for inflation.

In general, inflationary tax hikes hit middle- and low-income families more heavily than wealthy people because most of wealthier taxpayers’ income is already taxed at the top marginal tax rate. For someone making $500,000/year, five years of 5% inflation in an income tax without indexed tax brackets in the example on the previous page would hardly change his or her effective tax rate at all.

The way the federal personal income tax code and some state income tax structures deal with these hidden tax hikes is by “indexing” tax brackets for inflation. In Henrietta's case, indexing for inflation would mean that the $20,000 cutoff for the 4% tax bracket would be automatically increased every year by the amount of inflation. If inflation is 5%, the cutoff would automatically increase to $21,000 after one year. After four years (of five percent inflation), the 4% bracket would start at $24,310. So, when the person in our example makes $23,702 after four years, he or she would still be in the 2% tax bracket. In other words, indexing income taxes for inflation helps ensure that the tax system treats people in roughly the same way from year to year

Take, for example, a hypothetical state that taxes the first $20,000 of income at 2% and all income above $20,000 at 4%. A person, call her Henrietta, who makes $19,500 will only pay tax at the 2% tax rate. But over time, if this person’s salary grows at the rate of inflation, she will find herself paying at a higher rate -- even though she’s not any richer in real terms. In this example, suppose the rate of inflation is five percent a year and the person gets salary raises that are exactly enough to keep up with inflation. After four years, that means a raise to $23,702 (that’s a 5%/year raise from $19,500). Now part of Henrietta’s income will be in the higher 4% bracket -- even though, in terms of the cost of living and ability to pay, because the prices she must pay for goods and services, her income hasn’t gone up at all.

Of course, the problem of “bracket creep” is not limited to tax brackets. Any feature of an income tax that is based on a fixed dollar amount will have inflationary effects. In many states, this means that tax breaks designed to provide low-income tax relief -- including exemptions, standard deductions, and most tax credits -- are worth a little bit less to taxpayers every year. When all these small impacts are added up, the long-term effect can be a substantial tax hike -- and one that falls hardest on low- and middle-income taxpayers.

For example, when the Illinois income tax was adopted in 1969, the state’s personal exemption was set at $1,000 -- and was subsequently left unchanged for thirty years. 1998 legislation doubled the exemption to $2,000 -- but if the exemption had kept up with inflation since 1969, it would have been worth $5,800 in 2010. In other words, the Illinois personal exemption is worth $3,800 less than it originally was. As a result, Illinois taxpayers paid about $1.5B more in income taxes in 2010 than they would have if the exemptions had been adjusted to preserve their 1969 value. Of course, Illinois lawmakers never voted to enact such a regressive tax hike -- but this tax hike is the direct consequence of not indexing for inflation.

In general, inflationary tax hikes hit middle- and low-income families more heavily than wealthy people because most of wealthier taxpayers’ income is already taxed at the top marginal tax rate. For someone making $500,000/year, five years of 5% inflation in an income tax without indexed tax brackets in the example on the previous page would hardly change his or her effective tax rate at all.

The way the federal personal income tax code and some state income tax structures deal with these hidden tax hikes is by “indexing” tax brackets for inflation. In Henrietta's case, indexing for inflation would mean that the $20,000 cutoff for the 4% tax bracket would be automatically increased every year by the amount of inflation. If inflation is 5%, the cutoff would automatically increase to $21,000 after one year. After four years (of five percent inflation), the 4% bracket would start at $24,310. So, when the person in our example makes $23,702 after four years, he or she would still be in the 2% tax bracket. In other words, indexing income taxes for inflation helps ensure that the tax system treats people in roughly the same way from year to year

That all sounds basically fair, and to be sure, the intent of indexing is to inject a degree and genre of equitability into the tax code. The problems with the APRP using the CCPIU, however, are multiple:

- It tracks behind the actual rate of inflation; thus in "year one" the CCPIU indexing multiplier is one because that's the starting year. With each passing year, however, the multiplier increases cumulatively, so eventually, the CCPIU multiplier will surpass the inflation rate and that's when taxpayers begin to experience "hidden" tax increases. Later still, the thing turns the "creep" of brackets into a "dash."

So what one needs to think about is whether there's any good reason to think one's income will minimally keep pace not with inflation (CPI or CPIU) but with CCPIU. Whose income (wage/salary income) keeps pace with basic inflation? Put another way, whose pay increases result in increased buying power? For the most part, not the wages of low- and middle-income earners.- Wages not keeping up with pace of inflation

- Faculty Salaries Barely Keep Pace With Inflation

- Wages Fail to Keep Up with Inflation

- 5 facts about the minimum wage

- For most workers, real wages have barely budged for decades

What [wage] gains have been made, have gone to the upper income brackets. Since 2000, usual weekly wages have fallen 3.7% (in real terms) among workers in the lowest tenth of the earnings distribution, and 3% among the lowest quarter. But among people near the top of the distribution, real wages have risen 9.7%.

- Wages not keeping up with pace of inflation

- It isn't final until some two years after it's initially published. One can see the problems with that in terms of the preceding bullet's discussion -- the tax you pay "today" may be more than the tax you should have paid, but nobody will know for two years whether it is. Are you going to file an amended return to get your money back? Will you be allowed to do so? Will the IRS publish updated tax bracket boundaries? Oh, and BTW, one has only three years to file an amended return for a given prior tax year.

The IRS on the other hand and in general has six years to decide to audit one's federal income tax return. (There are some exceptions that give it even longer.) Will it wait until the CCPIU is finalized and then select returns to audit? Will it find some other way to assess more tax, fees and penalties as as a result of the delay? - Remember that notion of simplicity in the tax code? Well, insofar as the CCPIU is used as the indexing multiplier, it's not just folks like me who have relatively complex tax returns who'll be keeping boxes and boxes of tax-relevant documents for years. Anyone having before-AGI deductions will now and necessarily have a more complicated tax-minimization process, if for no other reason than that they will have to reexamine their returns from two years before every year to determine whether they may be due money from the IRS. I don't know that I'll be due money or owe money, but I (my tax accountant) will damn sure check to find out. If I'm owed money, I will file an amended return and likely be forced to be among the first to test the rules that address or don't address the questions noted in the previous bullet.

The focus here is on the APRP's percentage changes in households’ after-tax income, the measure that most likely best quantifies how tax law provisions affect households across the income spectrum. That’s because what affects people’s standard of living is a change in their after-tax (“disposable”) income, and looking at changes in after-tax incomes in percentage terms allows for fair comparisons among groups with widely different average incomes. This measure (excluding the impact of estate tax changes) can be calculated directly from the estimates that JCT presents.

For example, the JCT estimates households having incomes over $1M in 2027 will face a tax rate of 31.7 percent under the final bill, versus 32.1 percent under current law. Millionaires thus would have 68.3% of their income left after taxes under the APRP, versus 67.9% under pre-APRP law. The percentage change in after-tax income due to the APRP is thus calculated by comparing these two estimates. For millionaires, this calculation shows that, using the JCT's estimates, the final bill would increase after-tax incomes by 0.6 percent on average in calendar year 2027 (68.3 percent / 67.9 percent – 1 = 0.6 percent).

Other Organizations' Analysis of the CCPIU's Impact: [1]

Tax Policy Center:

According to the Tax Policy Center, taxpayers in the second income quintile (currently those with cash incomes of $25,000 to $48,600) would see the biggest percentage increases, with their tax rate going up by 0.4 percent and their after-tax income declining by 0.4 percent 15 years after a switch to CCPIU. Meanwhile, those in the top 0.1 percent of the income distribution (currently, folks having incomes above $3.4M) would see average percentage changes of effectively zero.

Center for Budget Policy and Priorities:

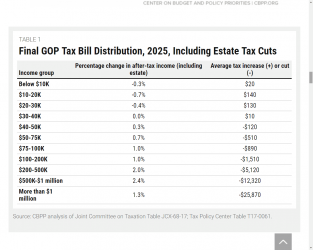

Shown here only for comparison with 2027, which is the year the CCPIU adoption most notably "kicks-in," the CBPP estimates that in 2025, the bill would:

Households with incomes below $30,000, on the other hand, would face tax increases, on average, for two main reasons over and above the CCPIU's implementation as the index for the tax brackets.

In 2027, people really start to notice the effect of tying tax brackets to CCPIU and the JCT's analysis show the results, and by incorporating the effect of factors the JCT does not -- the estate tax elimination (it too must be paid for), for example -- the impact becomes even more pronounced. [3] So what do the charts above look like in 2027?

It is worth noting that the the CBPP estimates that its figures understate the nature and extent of deleterious impact low- and middle-income households will experience as a result of the APRP's indexing tax brackets to the CCPIU.

Penn Wharton (PW):

PW attributes to the CCPIU an $88B increase (up from $83B, which was based on a November version of the JTCA) in tax revenue collected, whereas the JCT puts it at $134B; however, PW doesn't calculate the increase and distribute it to the various tax brackets. [4]

What does that tell us? It tells us that Congress, the Senate in particular, used the CCPIU to create a seemingly small and gradual tax increase to make the APRP compliant with the Byrd Rule.

Thinking about the JCT's Analysis [5]:According to the Tax Policy Center, taxpayers in the second income quintile (currently those with cash incomes of $25,000 to $48,600) would see the biggest percentage increases, with their tax rate going up by 0.4 percent and their after-tax income declining by 0.4 percent 15 years after a switch to CCPIU. Meanwhile, those in the top 0.1 percent of the income distribution (currently, folks having incomes above $3.4M) would see average percentage changes of effectively zero.

Center for Budget Policy and Priorities:

Shown here only for comparison with 2027, which is the year the CCPIU adoption most notably "kicks-in," the CBPP estimates that in 2025, the bill would:

- Boost the average after-tax income of households with incomes over $1 million by 1.3% or more than $25,000.

- Give far smaller tax cuts to those toward the middle of the income distribution. Households with incomes between $40K and $50K, for example, would get a percentage increase in after-tax income that is about one-fourth of what millionaires would see.

- Reduce the after-tax incomes of households with incomes below $30,000, on average, while doing virtually nothing for those with incomes between $30,000 and $40,000.

Households with incomes below $30,000, on the other hand, would face tax increases, on average, for two main reasons over and above the CCPIU's implementation as the index for the tax brackets.

- First, most of the bill’s changes to the individual income tax would largely end up being a wash for families in this income group and having one or two members, on average, because raising the standard deduction lowers their tax liability. Larger households, however, will see an increase because of the APRP's repeal of personal exemptions which at ~$4K/spouse or dependent, is not made up for by any other provisions in the APRP, and certainly not by the Child Tax Credit.

- Second, repealing the individual mandate hurts low- and moderate-income people overall, leaving millions more uninsured and raising premiums for millions more, and creating uncertainty across the health insurance market.

In 2027, people really start to notice the effect of tying tax brackets to CCPIU and the JCT's analysis show the results, and by incorporating the effect of factors the JCT does not -- the estate tax elimination (it too must be paid for), for example -- the impact becomes even more pronounced. [3] So what do the charts above look like in 2027?

It is worth noting that the the CBPP estimates that its figures understate the nature and extent of deleterious impact low- and middle-income households will experience as a result of the APRP's indexing tax brackets to the CCPIU.

Penn Wharton (PW):

PW attributes to the CCPIU an $88B increase (up from $83B, which was based on a November version of the JTCA) in tax revenue collected, whereas the JCT puts it at $134B; however, PW doesn't calculate the increase and distribute it to the various tax brackets. [4]

What does that tell us? It tells us that Congress, the Senate in particular, used the CCPIU to create a seemingly small and gradual tax increase to make the APRP compliant with the Byrd Rule.

The new tables from JCT, Congress’ official estimator of tax legislation, show how the bill affects households, on average, in different parts of the income distribution for 2019 and every second year thereafter until 2027. Because the JCT estimates exclude the bill’s estate tax cut and present a limited set of distributional measures, understanding them requires some analysis and adjustment. Below is discussed what the JCT tables show about the impact of the bill, both in 2025 and in 2027.

The focus here is on the APRP's percentage changes in households’ after-tax income, the measure that most likely best quantifies how tax law provisions affect households across the income spectrum. That’s because what affects people’s standard of living is a change in their after-tax (“disposable”) income, and looking at changes in after-tax incomes in percentage terms allows for fair comparisons among groups with widely different average incomes. This measure (excluding the impact of estate tax changes) can be calculated directly from the estimates that JCT presents.

For example, the JCT estimates households having incomes over $1M in 2027 will face a tax rate of 31.7 percent under the final bill, versus 32.1 percent under current law. Millionaires thus would have 68.3% of their income left after taxes under the APRP, versus 67.9% under pre-APRP law. The percentage change in after-tax income due to the APRP is thus calculated by comparing these two estimates. For millionaires, this calculation shows that, using the JCT's estimates, the final bill would increase after-tax incomes by 0.6 percent on average in calendar year 2027 (68.3 percent / 67.9 percent – 1 = 0.6 percent).

Closing Rubric Remarks:

The code doesn’t only index tax brackets. Some other provisions, including the standard deduction, the personal exemption, Earned Income Tax Credit, and the Alternative Minimum Tax, are also indexed for inflation.

Many economists believe that chained CPI more accurately reflects inflation by accounting for the way consumers respond to price changes. The classic example: If the price of oranges rises, consumers may buy more apples. CCPIU does a better job reflecting that change, though it has some disadvantages as well. If you want to know more, here is a nice explanation by my Tax Policy Center colleague Rob McClelland, written when he was at the Congressional Budget Office.

But the bottom line is that chained CPI is consistently lower than traditional CPI-U. Using CCPIU may result in a more accurate inflation adjustment, but it also raises taxes for many since those indexed provisions of the Tax Code would be less generous over time than under today’s methodology.

That means people would pay higher income taxes than under current law. It would especially hit low- and moderate-income households that rely on the CTC and standard deduction, but it would affect all taxpayers in some way, though taking longer, far longer, to percolate into the upper income brackets. And unlike proposals to repeal, say, itemized deductions, people for years to come not only will not notice, and likely not understand it if they do notice it, this hidden tax increase.

- It's worth noting that literally everyone's analysis derives from the quantitative analysis performed and published by the JCT. The JCT's (and/or CBO's) analysis is the "analysis of record" for Congress. The CBO and JCT are nonpartisan economic "think thanks" that support the U.S. Congress.

It is important to note that the CBO and JCT are nonpartisan organizations rather than bi-partisan organizations. The reporting and analytical approaches and constraints of the two types of groups are materially different; however, it is possible for credible information to issue from both kinds of organizations/individuals.- Nonpartisan --> Nonpartisan groups and individuals are indifferent about partisan considerations and impacts. That doesn't mean they are not unaware of them. It means they do they jobs and issue their reports without regard to whom their remarks favor or disfavor. Though economists publish their research findings without regard to politics, the empiricists among them care even less about political than do the "regular" economists. That the JCT is nonpartisan is why it (and the CBO's baseline analysis is so often used by other organizations. It's reliable, accurate, and frankly, cheaper....Why replicate someone else's highly credible work?

- Bi-partisan --> Bi-partisan groups/individuals are unequivocally and unabashedly comprised of every kind of partisan who can get themselves into the group. Such groups/organizations "haggle" about what, in their reports, they say and how they say it. Generally, their aim is include in their reports "bones" for their respective political supporters. That is very different from doing the research, letting the "numbers" fall where they do, and reporting as much.

- How do we know it's "most people?" Because the median household income in the U.S. is somewhere around $55K/year and the reversal by 2027 will affect only people having =< $75K/year incomes.

- The normative discussion point here isn't how pronounced the impact be; it's that the CCPIU indexing impact, that of reversing the tax cut, has been incorporated into the APRP at all.

- PW has several essays that discuss how CCPIU can be used in association with various other economic policy measures.

- The Child Tax Credit: Options for Expansion

- The Penn Wharton Budget Model’s Social Security Policy Simulator

- Options for the Unified Framework Tax Plan

- The Senate Tax Cuts and Jobs Act, as Passed by Senate (12/2/17): Static and Dynamic Effects on the Budget and the Economy -- This along witih other earlier analyses at PW and the other organizations' sites afford one the opportunity to see how small changes have material impacts.

- The Child Tax Credit: Options for Expansion

- The Case for and against CCPIU is outlined here: Commentary: The Debate Over the Chained CPI